Most investment firms kick off the new year with “outlook” pieces, offering futile predictions on the S&P 500’s year-end close or the frequency of Fed rate hikes. I try to avoid such oracular activity and stick to analyzing the present, which isn’t as easy as it first sounds. But I do read many of these tomes – if brevity is the soul of wit, Wall Street is witless – so I can monitor the consensus view, primarily because it is almost always wrong. Knowing what isn’t going to happen is almost as valuable as knowing what is.

The consensus I gleaned from this year’s crystal ball gazing efforts was that 2026 would be a year of “stability” and falling policy uncertainty. It took only 17 days for that narrative to crumble. On January 17th, President Trump announced a 10% tariff on Denmark and seven other European nations in an escalation of his bid for Greenland.

Trump Announces New European Tariffs in Greenland Standoff; Allies Outraged

New York Times

Other notable signs of stability include:

- Geopolitical Tensions: Mass demonstrations in Iran with threats of U.S. intervention.

- Domestic Unrest: Riots in Minneapolis and Chicago following a fatal confrontation between a citizen and ICE.

- Foreign Interventions: U.S. military action in Venezuela to capture Nicolas Maduro, followed by the seizure of Venezuelan oil production with little apparent long-term planning.

Anyone expecting policy certainty during this administration is on a fool’s errand.

The Myth of “Low Impact” Tariffs

Another common theme in the 2026 outlooks was that businesses could finally “adjust” to the new tariff regime. Bulls argue that the tariffs weren’t that bad because effective rates turned out lower than the announced rates (due to substitution and evasion) and that aggregate data shows little harm. Indeed, through Q3 2025, real GDP growth sat at 2.3%—right in line with the long-term trend. The inflation rate, while still above the Fed’s target, is also right in line with the long-term trend.

However, looking at aggregates obscures the reality of winners and losers. Tariffs generally protect the few at the expense of the many. A few industries or favored companies get the benefits while everyone who uses their products pays the price. Primary metals producers added to payrolls last year while manufacturing shed jobs in nine of the last twelve months. Since the April tariff announcement, there hasn’t been a single “up” month for manufacturing employment.

The post mortem on the steel and aluminum tariffs from Trump’s first term showed that job losers far outnumbered job gainers. I guess the thinking in his second term is that if a little didn’t work maybe a lot will so, he raised them and added copper to the bill of particulars.

Contradictory Policy Goals

The administration claims tariffs will revive American manufacturing, but their policies are often self-defeating. Steel, copper, and aluminum tariffs imposed for national security reasons make it more expensive to re-shore manufacturing and create all those iPhone screw turning jobs Commerce Secretary Lutnick promised us.

Energy policy is similarly muddled. While seizing Venezuelan oil might temporarily lower gasoline prices, if crude stays below $60 for too long, domestic production in the Permian Basin will stall – and may have already peaked in any case. Improving a consumer’s purchasing power in New England comes at the expense of job losses in West Texas or North Dakota, where drilling has already slowed.

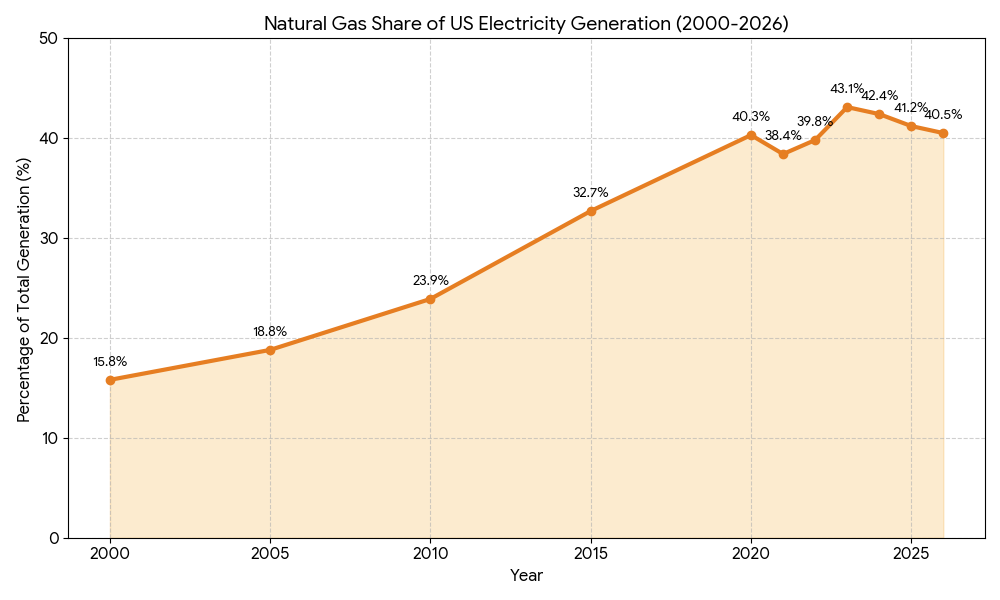

Furthermore, lower shale oil production leads to lower natural gas production. Unlike twenty-five years ago, today’s natural gas prices translate almost immediately into higher electricity bills.

The AI Infrastructure Bottleneck

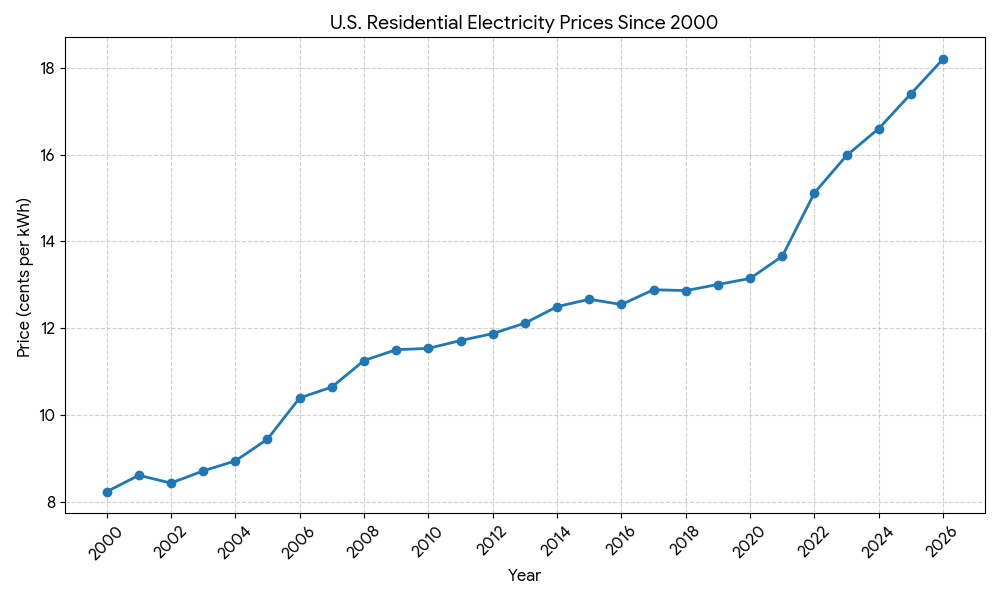

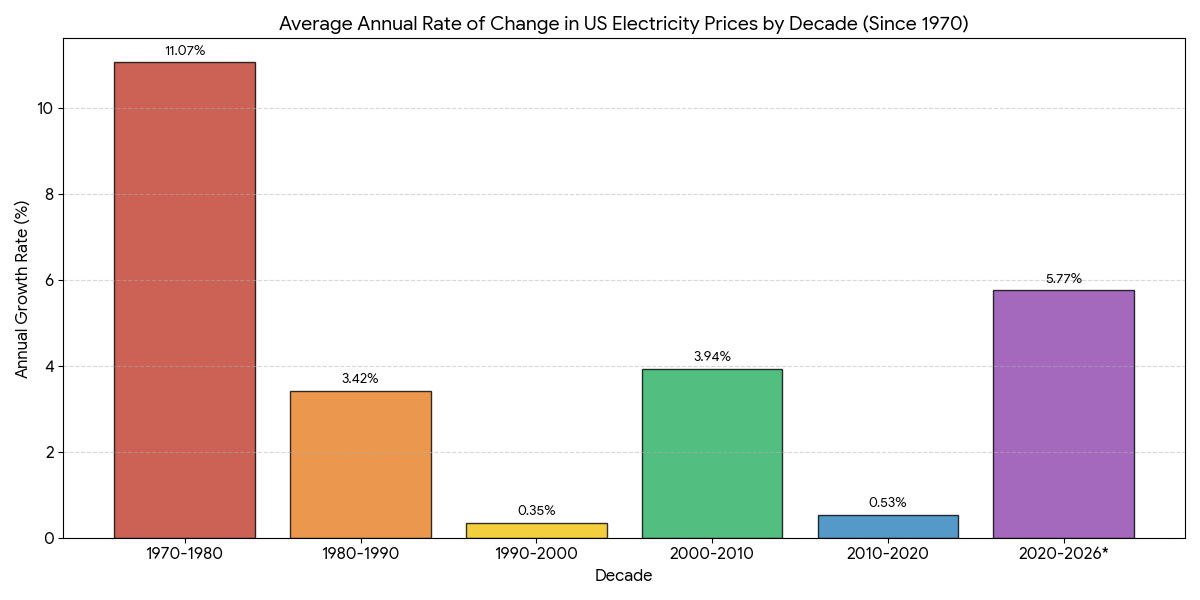

Electricity prices are skyrocketing due to the AI infrastructure buildout.

This decade’s price surge is exceeded only by the 1970s. Tariffs exacerbate this by raising the cost of copper, aluminum, and steel—the very materials required to build data centers and power plants.

The labor market presents another hurdle. Building the “AI future” requires a massive influx of skilled tradespeople. Electricians, HVAC technicians, plumbers, welders, and carpenters are in high demand right now and all are expected to continue growing rapidly over the next 10 years.

| Trade Occupation | 10-Year Growth Rate | 2026 Median Salary (Est.) | Primary Growth Driver |

| Electrician (Nuclear) | 14.0% — 18.0% | $105,000+ | Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) for data centers. |

| Electrician (Standard) | 9.00% | $72,500 | EV infrastructure and commercial AI builds. |

| HVAC Technician | 8.50% | $68,000 | Advanced liquid cooling for AI server farms. |

| Ironworker | 6.00% | $63,000 | Structural steel for massive hyperscale shells. |

| Plumber / Pipefitter | 5.00% | $74,000 | Industrial piping and high-tech liquid cooling. |

| Welder | 3.0% — 5.0% | $61,000 | Manufacturing and infrastructure hardening. |

| Carpenter | 1.50% | $58,000 | Lagging due to shifts toward modular construction. |

As demand for these skills rises for data center construction, wages rise, affecting the costs of all other construction. Our inability to build new generating capacity rapidly will likely act as brake on AI development at some point. Electricity demand flatlined in the 2010s but started to rise after COVID and accelerated in 2024 (3%). Demand from data centers and EVs will likely keep demand growing at that rate – or more – for some time, as long as we can generate the electricity to run it.

The non-data center construction industry was already short-staffed because of AI even before the recent immigration crackdown. Now, a lack of immigrants could mean that entry-level apprentice roles go unfilled and the shortages persist. One wonders how many houses weren’t built last year due to construction labor shortages and how much AI and tariffs added to the cost of the ones that did get built. The administration’s solution to housing affordability—allowing people to use 401(k) funds for down payments—is economically illiterate. Increasing demand in a supply-constrained market will only drive housing prices higher while using retirement accounts to fund it will only worsen the existing shortfall in retirement savings. If you want to fix housing, you have to work on the supply side.

The Scarcity Age

We are entering an age of scarcity. Our population is aging, prime working age labor participation is near an all-time high and population growth this year will likely be nil if not outright negative due to current immigration policies. AI is often touted as a solution to labor shortages, but building that AI capability is incredibly resource-intensive and, ironically, requires a lot of skilled workers. A single hyperscale data center requires roughly 50,000 tons of copper and 15,000 tons of steel. Meanwhile, the copper, silver, uranium, platinum, and aluminum markets are all already in supply deficit and we’re going to need a lot more. An AI bot requires 10 to 20 times the energy of the human it replaces.

The administration’s political aims are in direct conflict with its economic goals.

- Immigration policy exacerbates labor shortages in critical trades, raising the cost of data centers and houses alike.

- Tariff policy raises the cost of raw materials needed to construct our HAL 9000 future

- Security-driven tariffs undermine the goal of re-shoring manufacturing.

This is what F.A. Hayek called “The Fatal Conceit”—the hubris of believing that the government (the President) can predict and control the complex interactions of the global economy. With policy today set seemingly on a whim – how carefully do you think these Greenland tariffs were considered before their announcement on social media? – the potential for a misstep is high. Anyone who believes the next few years will bring more certainty, more predictability, simply isn’t paying attention.

Stay In Touch