The month of February 2022, the calm before the latest storm. Russians went into Ukraine toward the month’s end, collateral shortage became scarcity, maybe a run right at February’s final day, and then serious escalations all throughout March – right down to pure US Treasury yield curve inversion.

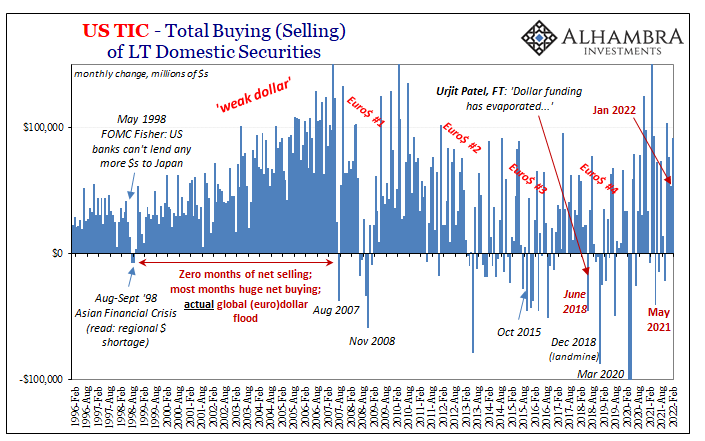

Given that setup, it was unsurprising to find Treasury’s February TIC data mostly unremarkable. Top to bottom, there wasn’t really much that changed. No huge negatives, nor positives, either. Much of the same, therefore February became March.

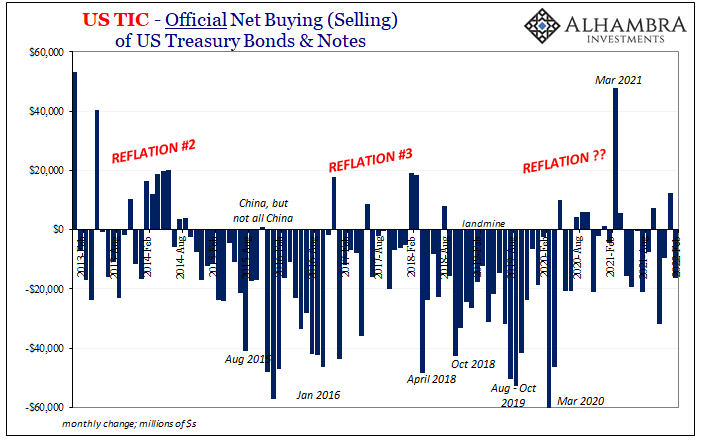

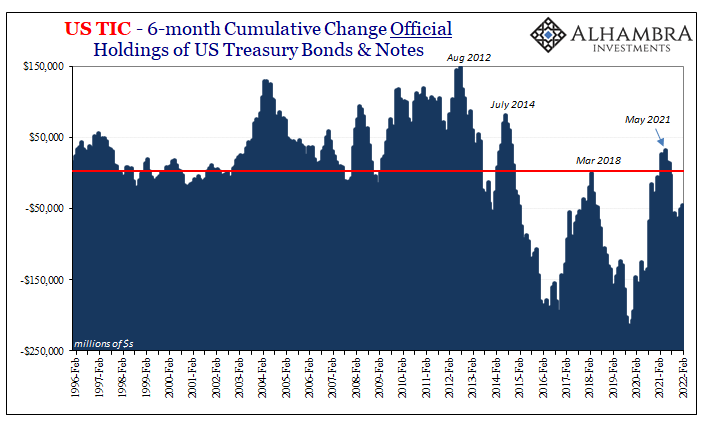

While waiting another month to see what TIC has to say about last month, there were a few highlights worth mentioning from the current update. Officials overseas sold a few more Treasuries, foreigners on the whole bought more US$ assets (since October, this has been up almost certainly because of merchandise goods finally being delivered to the US and elsewhere).

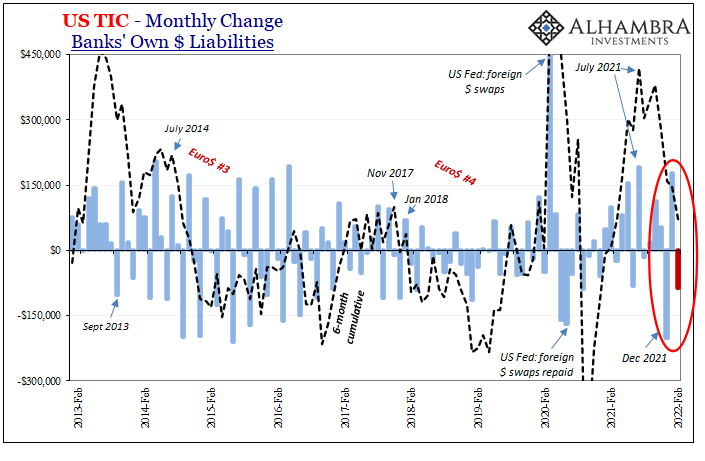

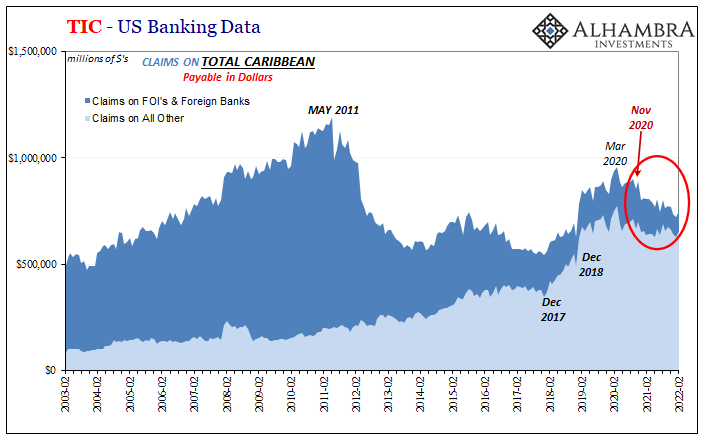

If there was a standout datapoint, it would have to be US bank liabilities due to foreign counterparties. There is a very close if general relationship between what US banks are doing from on the outside and what seems to happen overall as far as global dollar shortages may be concerned.

Quite simply, fewer reported liabilities equate to broad reserve currency money problems (including collateral). The figure for February 2022 was negative (below), but since month-to-month changes tend to be very noisy here we look at it from a cumulative six-month perspective. And while still quite positive, as you can see the trend isn’t at all friendly nor favorable.

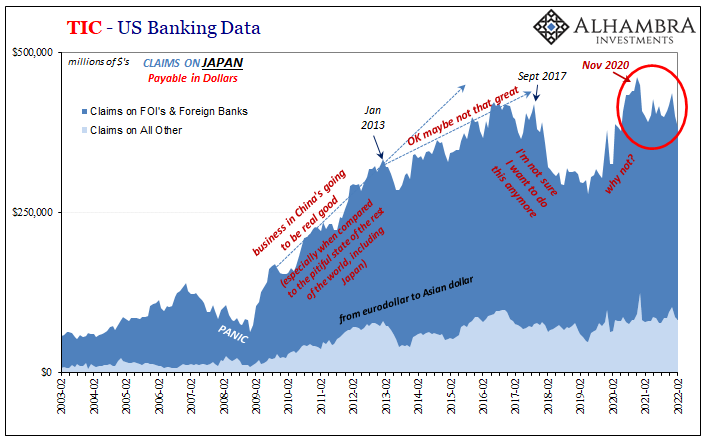

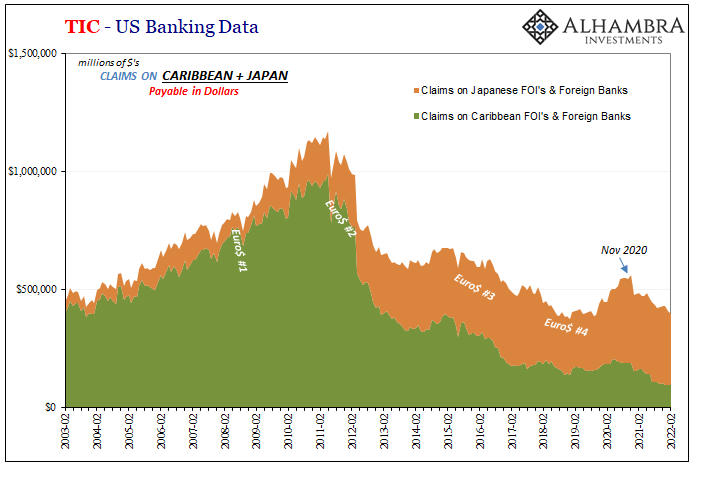

Furthermore, we have to note where this may be coming from. Looking at it from the other direction, now US bank claims on foreigners rather than liabilities to them, Japan, Japan, Japan. After a few months running slightly higher November and December, the balance of claims on Japanese counterparties sunk January and then more in February (-$54.8 billion combined).

This isn’t really about Japan so much as Japanese banks redistributing “dollars” (with yen swapped into them as collateral) into, or out of, as the current case may be, China, China, China.

Weakness therefore risk abounds across the Chinese financial and economic system, just like Euro$ #4 in 2018. Only COVID blamed today in place of the “trade wars” everyone cited a few years ago. The problem both times represented instead by Xi’s post-19th Party Congress directives which have only become more regressive through time.

If you are a Japanese bank, get out while the getting is good? Not just plausible, reasonable to the point of being downright prudent no matter what the mainstream media or Bank of Japan says.

The timing fits only too well for what has shaped up to be a sustained (euro)dollar “hole.” Thus, overall, we’d be forgiven for expecting China to fend more and more for itself through other means.

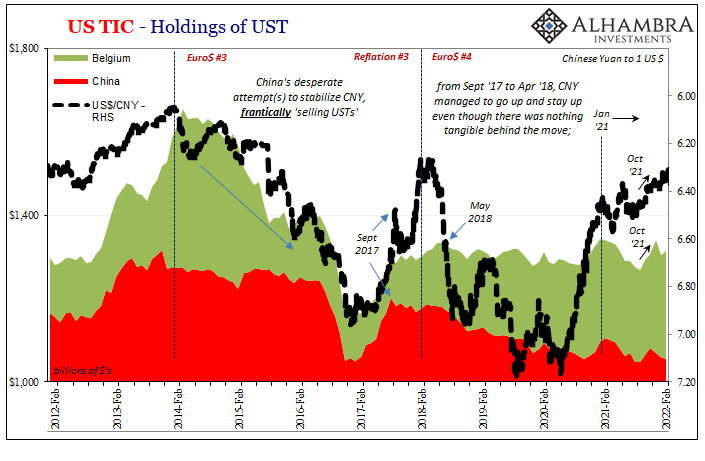

According to other TIC data, Chinese mainland holdings of US Treasuries as reserve assets unsurprisingly fell again in February, too. That balance continues to shrink over time at the same time China’s official financial actors, SAFE and the PBOC, keep reporting limited or no gains in their forex holdings in general.

While many (those using the term “petrodollar”) will still claim anyone selling Treasuries is doing so because – Asians in particular – they hate America and are planning the US dollar’s demise, we know that this is false, has been false for six decades, and that foreigners are instead forced to sell their Treasuries (or other kinds of reserve assets) when local banks find their eurodollar activities more difficult, costly, increasingly improbable to carry out.

Just like it had been more than half a century ago:

Unwilling to see any eurodollar default posted to the Japanese system [in December 1963], the Bank of Japan ordered its American reserve custodians in New York City to liquidate the same $200 million in Treasury bills being held on behalf of the Japanese government (the responsibility of BoJ). The proceeds from the sale were used to close out the eurodollar short, establishing a precedent that remains, and remains misinterpreted, to this day.

At the same time as China reporting fewer, another substantial deposit of the same was made by someone into Belgium’s Euroclear. This time unlike December’s much larger payment, I doubt it was anything to do with Russians (who have almost certainly removed as much as possible from any Western reach).

Not just that, all of a sudden a rather substantial drop was reported in Hong Kong’s February holdings of UST’s, too. Chinese woes stepped up so as to reactivate the long-dormant 2017-style HK bypass? Wouldn’t that be something!

Altogether, China’s -$5.3 billion plus HK’s -$20.2 billion more than cancel out Belgium’s +$15.5 billion. Those also would seem consistent with fewer US bank transactions going to Tokyo where we don’t know but we can guess lending less into China – forcing the Chinese to use more of their own stash, or seek borrowing via contingent liabilities or other off-balance sheet arrangements perhaps sourced from European derivatives market clearing located in Brussels.

The above mere speculation, of course, but it’s the same thing every time so also more than reasonable to apply the same speculation yet to be disproved.

And just the prelude for what might’ve followed in March eurodollar-wide, all this in February would certainly be consistent with the latest RRR cut (itself a later warning) by April, and, extrapolating this bank data forward into March and now April market prices, it’d be equally reasonable to expect more of the same still to come.

Probably not as generally unremarkable moving forward, though. Especially as the UST yield curve re-inverts again.

Stay In Touch