The bond market is allegedly populated by the “smart” set, whereas those trading equities derided as the “dumb” money (not without some truth). I often wonder if it’s either/or. The fixed income system just went through this scarcely three years ago, yet all signs and evidence point to another repeat. So, how smart can Eurobond agents really be if they’ve gone and done it again?

What is it?

Let’s roll the clock back to the landmine of 2018. Collateral shortage, financial chaos, rising dollar and all that stuff.

But, Argentina has been an absolute darling, a media frenzy and Wall Street hero. Since 2016, the Eurobond market had embraced this long-shunned section of South America. Where before this poor country couldn’t sell one single dollar in securities no matter how high the coupon attached, in 2017 in particular the world couldn’t get enough Argentine paper at any price.

In the context of securities lending, that would’ve meant right around the end of 2017 Argentine debt almost certainly was given more favorable terms (in securities lending) than it should have ever been afforded. I don’t know for sure if it was subprime MBS-like friendly, but undoubtedly way too far in the same direction. Argentina bonds were great because everyone loved Argentina.

Then they didn’t.

A Eurobond is simply a debt instrument issued outside the home country of the borrower (who could also be a private non-financial company, not just sovereigns or banks). Typically denominated in US dollars, the borrowing could be in whichever currency the obligor requires at the time (usually dollars).

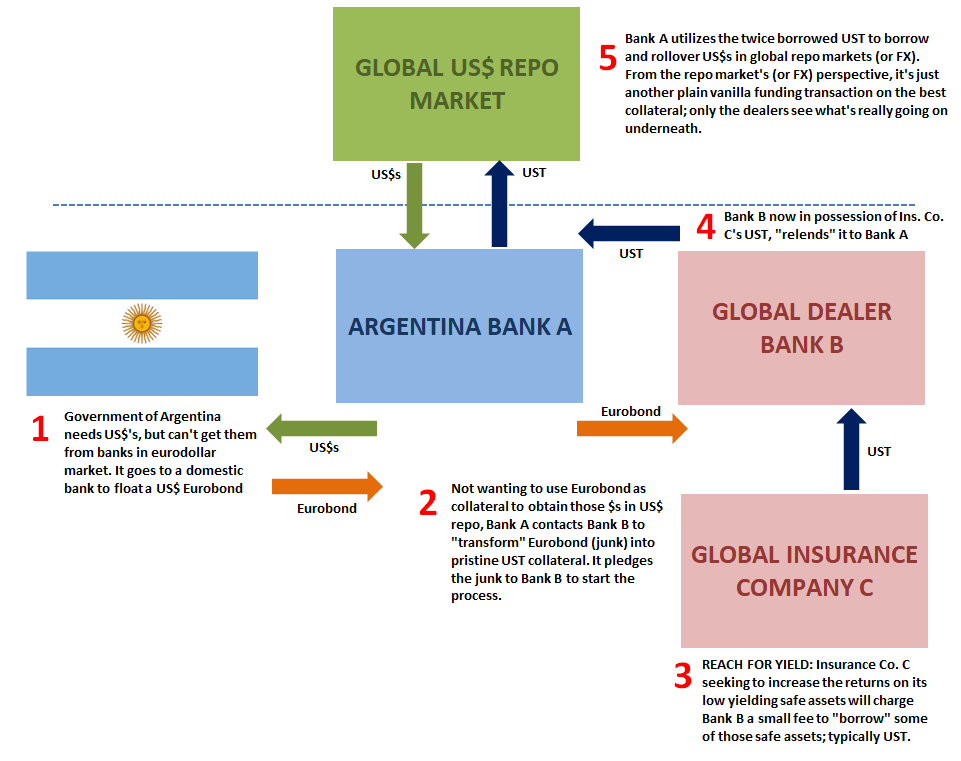

Sounds simple enough, but there’s more. Here’s a pretty straightforward sketch behind “more” and where it all intersects with repo, collateral, the real fun stuff:

During 2017’s “globally synchronized growth” fiasco, Eurobond investors and the dealer banks who sit in between all the heavy financial arrangements got drunk on central bank assurances that the “growth” part was real this time.

Spoiler: it wasn’t. In never is; false dawns only.

Realizing this, a chain reaction triggers for a whole bunch more than Argentina Eurobonds: when everyone loved Argentina and “globally synchronized growth”, that and so much other junk was let infect the global collateral stream. Transformations as shown above along with straight up use as collateral, much supported by shake-your-head quality credit.

Then, 2018, they didn’t love Argentina; collateral shortage system-wide as haircuts got adjusted and collateral calls (May 29, 2018) issued for better quality (USTs and the like). Once that becomes clear, everything on the chart above must reverse. The dealer (Bank B) isn’t going to accept the Argentine Eurobond as collateral in its collateral-for-collateral swap delivering the Insurance Company C’s UST. This leaves Argentina Bank A exposed, unable to rollover in US$ repo unless it can somehow find better collateral to post to repo or to swap.

We don’t really know ultimately how this Euro$ #4 basis would’ve played out in the end, the coronavirus came along and the rest is buried under forgotten history.

On the other side of it, however, history apparently repeated because the Eurobond market is either truly that stupid or so plain gullible combined with short-termism and an unreasonable ability to rationalize central bank promises and projections.

What do I mean? In late 2020 and early 2021, maybe Argentina wasn’t back in the Eurobond game…but a whole bunch of others came to be, including some of the worst credits in Africa. Countries like Ghana and Zambia have been issuing Eurobonds almost like Argentina once did.

Having floated billions last year, the Ghanian government today complains repeatedly that its Eurobonds have been unfairly singled out, having crashed for reasons beyond fundamentals. Officials there, of course, blame the Federal Reserve and its “rate hikes” because they like everyone else including the entire financial media has been taught to think only in those terms; if something happens, must be central bank.

The problem is collateral, not Jay Politics Powell.

How do we know? Let’s check the spreads.

Unfortunately, there just isn’t enough (or really much) data on Eurobonds let alone the spreads (above USTs) for them (let alone Eurobonds used as collateral in multi-leg reuse transactions). In lieu of anything else, it’ll suffice to pull out a couple of single issues trading in Luxemburg.

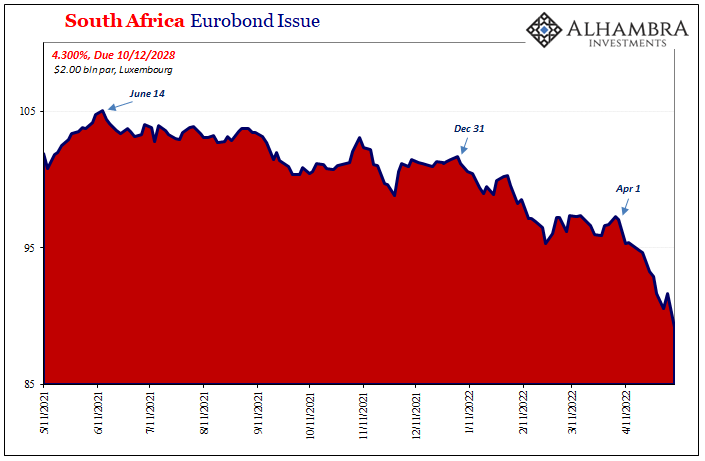

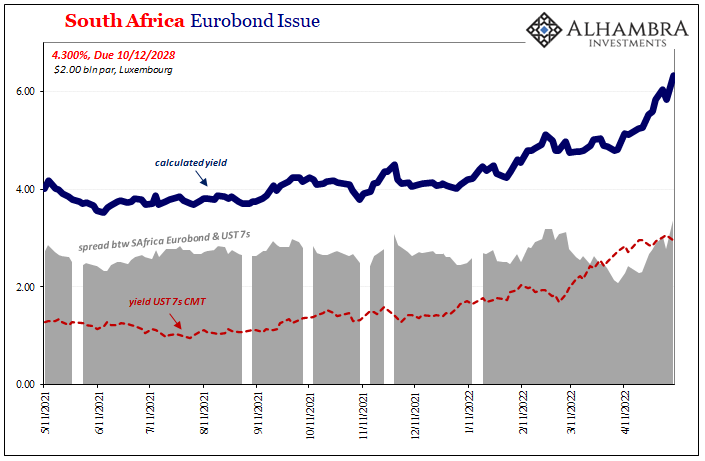

First up, a control of sorts, one from South Africa which is one of the better-quality credits floating around the offshore marketplace.

Prices down, yields up and mostly keeping in line with the similar 7-year UST. The South African government, if it wanted, really can blame Powell’s rate hikes because the interest rate environment (all in US$s) is clearly behind the fall in this Eurobond’s price.

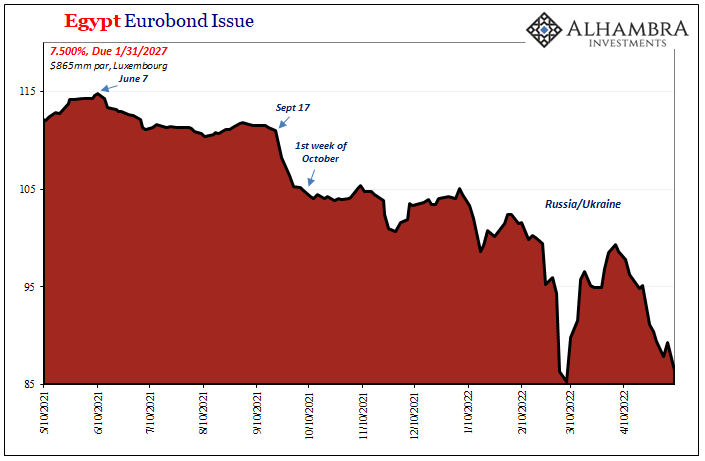

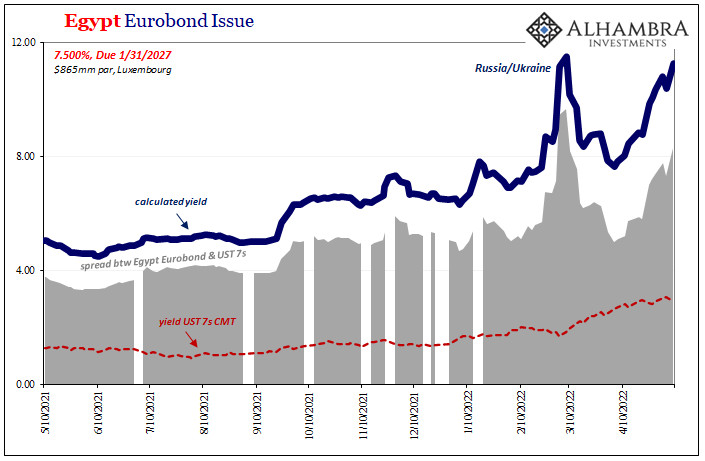

Among Africa’s lesser quality issuers, however, it’s definitely not FOMC policy behind bond plunges. And while I don’t have any Eurobonds from Ghana or Zambia to show you, I can choose a number from Egypt which will stand in just fine for those.

First off, a higher coupon because of its perceived higher risk that eventually offers no shelter once the system goes astray.

And while it would be easy to blame the likely-to-be-seriously-bad fallout from the war in Eastern Europe (especially in terms of food prices or even availability in Egypt), bond prices have been falling for much longer than Russians have been in the rest of Ukraine; spreads were going up and rapidly, particularly that bump late September/early October and then again around December 1. By early February, the spread was already sneaking up toward 575 bps from last June’s low of 340 or so.

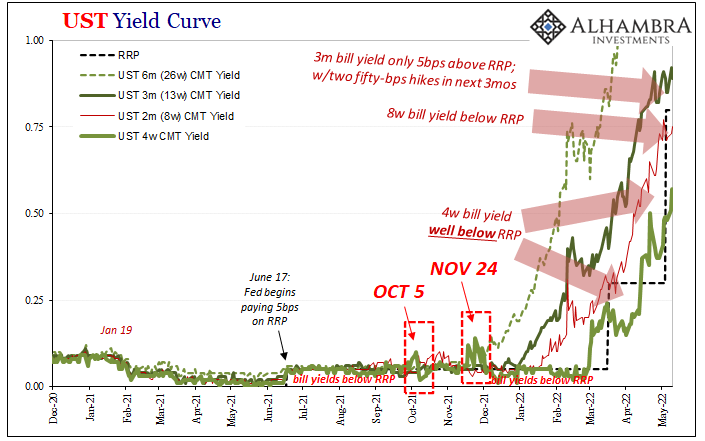

Those two time periods – October and December – should ring all sorts of bells where the systemic collateral condition has been concerned. Repo fails, etc. The already ironclad collateral case for curves in 2021 and 2022 is clad in even more iron from the Eurobond forge.

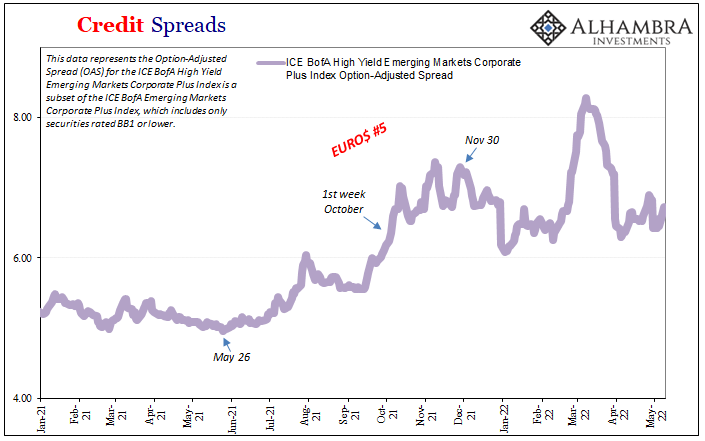

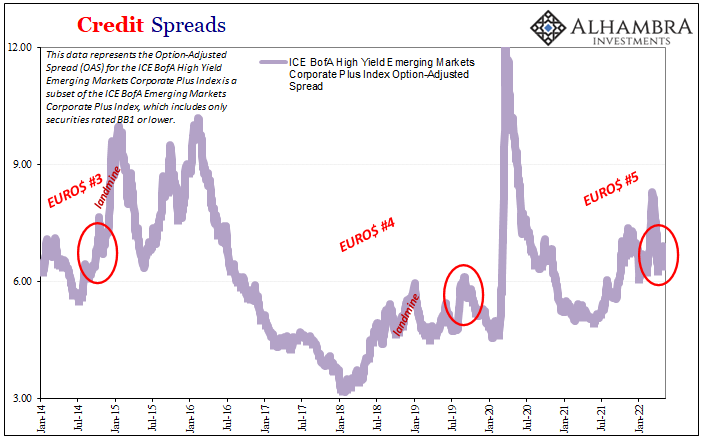

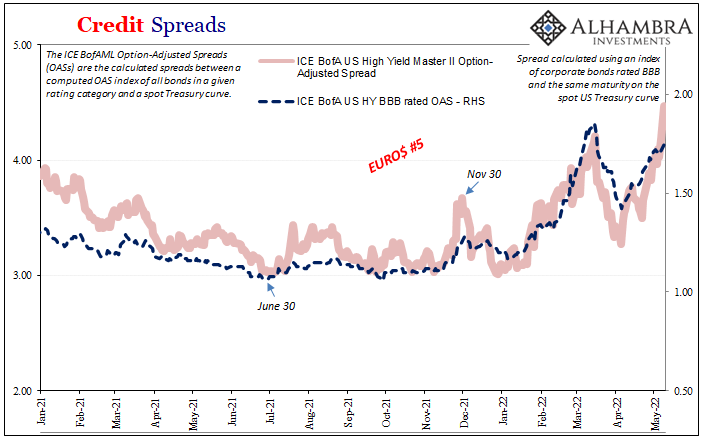

In fact, you can compare the spread on Egypt’s one Eurobond to others that are more generalized, such as ICE’s option-adjusted calculation for emerging market corporates as a group. The chart immediately above looks quite a lot like the one immediately below.

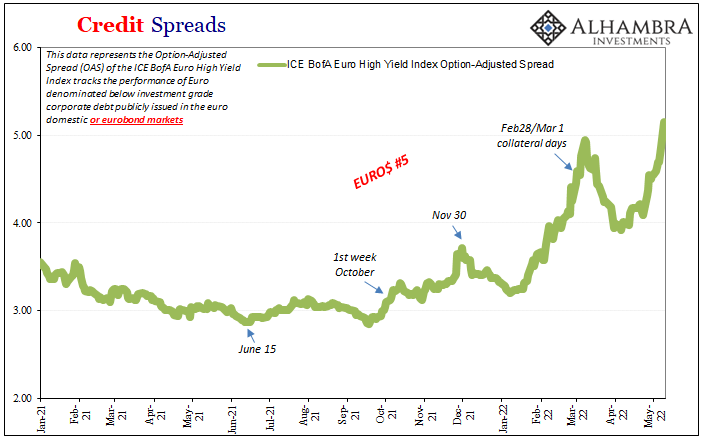

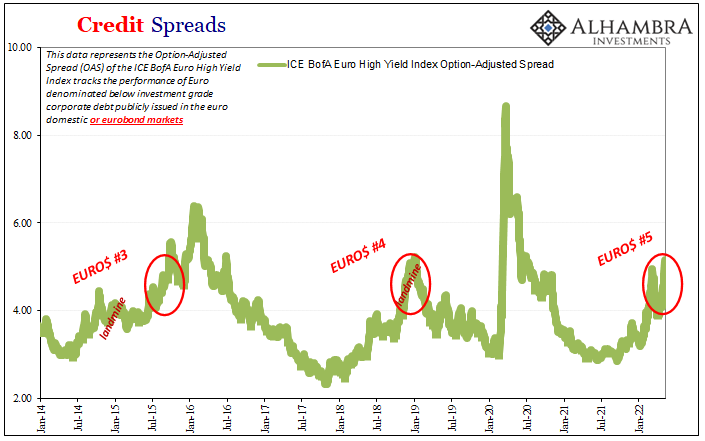

The Egyptian Eurobond spread also looks even more like the two charts above. These in the green are euro-denominated “high yield” corporates, though they also include more than a few placed in the Eurobond market, too.

In other words, it’s not just Egypt nor is it primarily dollars or Eurobonds. There’s a whole lot of systemic risk aversion especially in market segments which correspond and connect with those first. In them, for some of these spreads, Euro$ #5 has already surpassed Euro$ #4’s worst point, beginning to rival spread levels from late 2014/early 2015’s Euro$ #3.

This spread widening throughout weaker-quality collateral instruments has also and already spilled over into domestic issued corporate junk, if not yet with the same amount of puking.

Credit spreads aren’t blowing out, the market isn’t blowing up, rather it’s the opening stages for the link between falling prices and risk aversion which has been well-established as a key collateral factor globally. It starts at the outer edges, the more stupid of the Eurobonds, and then moves closer to the center.

That center isn’t the Fed nor its inert, useless bank reserves, rather the herding instincts of increasingly risk averse dealers who more and more will only deal in the better issues of collateral the more this thing, Euro$ #5, keeps going.

Back in the middle of 2018, even the rate-hiking hawks of the FOMC couldn’t help but acknowledge the sudden “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” as officials called it (trying to downplay the whole thing). They never could quite figure out why. Safe, yes, but more so highly and dependably liquid.

The collateral multiplier had shrunk once the real monetary system rethought and then repriced if not rejected so much stupid junk.

Ghanian or Egyptian Eurobonds might’ve been thought reasonable last year on those terms, absurdly the same terms as “globally synchronized growth.” Now that another false dawn, a Euro$ #5 steps over the horizon, here we go again.

History repeats because everyone listens to the Fed.

Stay In Touch