The stock market hasn’t been moneyed; well, US equities, anyway. What do I mean by “moneyed?” Common perceptions (myth) link the Federal Reserve’s so-called money printing (bank reserves) with share prices. Everyone still thinks there’s a direct monetary injection in this case by the central monetary agency which causes stocks to rise for no good reason.

While we don’t have to argue the Fed’s bank reserves here, the truth of the matter is stocks have been severed from any part of the actual and effective monetary system since 1929. First, the collapse in share prices started the severing before government regulation finished the job generations ago.

This is why, for example, the Crash of ’87 is remembered exclusively in Wall Street legend rather than the first modern restart of depression economics (small “e”). Similarly, the dot-com crash led to nothing more than a piddling recession. Behind both of those had been a ghastly yet growing eurodollar system undeterred by equity prices because there was no direct assembly.

Obviously, very different story starting 2007. Eurodollar falls apart, stocks follow, depression the result because of money not shares.

The Great Depression, on the other hand, had unfortunately and directly brought these two things in close combination. The primary reason why Wall Street’s stumble led to the massive deflationary money of the early thirties was something called call money, or alternatively classified as street loans.

Early 20th century bank innovation had spread interbank networks, building upon the more primitive correspondent system developed in the 19th century. Basically, smaller banks held deposit accounts with larger banks (who had correspondent accounts with even larger firms in the biggest cities, particularly NYC) in order to process ledger payments (checks and wires) across greater distances at far better speeds customers of a truly nationalized economy demanded.

But what to do with that correspondent balance while just sitting there waiting for a depositor payment to request some of it? Throughout the twenties, enterprising central reserve city banks, particularly those in NYC, began to offer “safe” returns on correspondent balances to those banks in the tiers below them (reserve city banks).

Essentially a repo, or a basic collateralized lending arrangement, a reserve city bank (not likely a country bank) would “invest” some of its correspondent balance in street loans offering a juicy return. The borrower of this call money (because it was a correspondent balance, the loan needed to be available at a moment’s notice, on call, therefore highly liquid) would use the proceeds to buy, yep, stocks.

Those stocks were then posted as collateral for the street loan. From the perspective of the respondent reserve city bank, it was as risk-free as risk-free could ever seem; brokered by the top NYC firms, secured by an asset whose price only ever goes up.

Until it didn’t.

Thus, when Black Tuesday struck, it wasn’t just a portfolio issue for shareholders planning for retirement. It was immediately a monetary matter for the whole damn system, as losses on shares meant the death spiral in correspondent balances and relationships; everyone tried to get their “money” out at the same time, leading to several years of deflationary chaos since there simply wasn’t enough liquidity (and, as Milton Friedman noted, the Fed stood idly by wondering what all the fuss was).

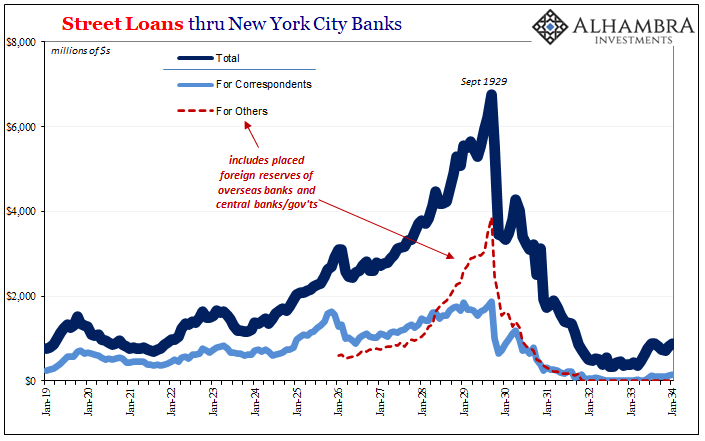

Street loans, however, weren’t strictly a domestic issue. How did the Crash of ’29 become the spark which lit the global Great Depression? This:

The massive rise in call money in NYC secured by that ancient equity bubble was financed by more overseas “reserves” than it ever was domestic correspondents. In fact, the blow-off part of the bubble, 1927 to October 1929, was from foreign correspondent reserves flooding the US and, like reserve city correspondents, offered the “safe” yet fat returns in street loans.

Destroyed by Wall Street’s debacle, deflationary money spread worldwide.

What follows is not to claim the current world’s monetary system is as it was in its most fragile state in late October 1929. As I started out, stocks have been neatly parted from money in the US$ sense. At least, domestic stocks.

How about the other side of the eurodollar world, though?

In places like, say, Hong Kong where global trade meets global finance in bulk with the eurodollar system involved in every possible angle in between them, might there still be a connection between correspondent relationships (especially those involving China on one side, both merchandise transactions as well as financial flows) and the perceived safe haven of the city’s various financial outlets?

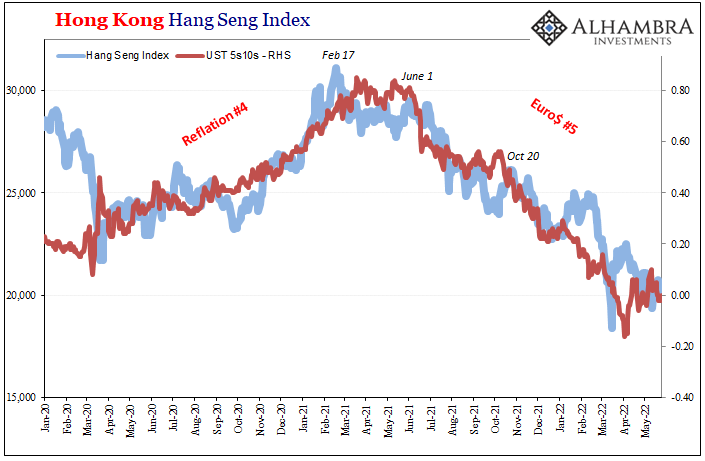

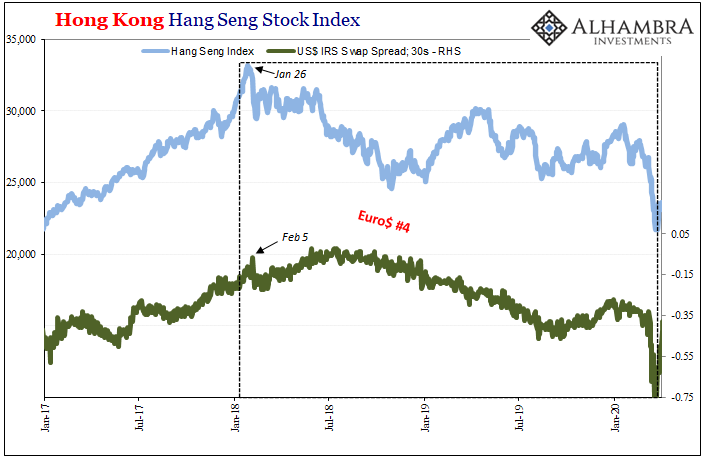

It seems as if there just might be. The Hang Seng stock index, for example, correlates a little too closely (though not exactly) with the repeated episodes of eurodollar shortages.

Starting with the current one:

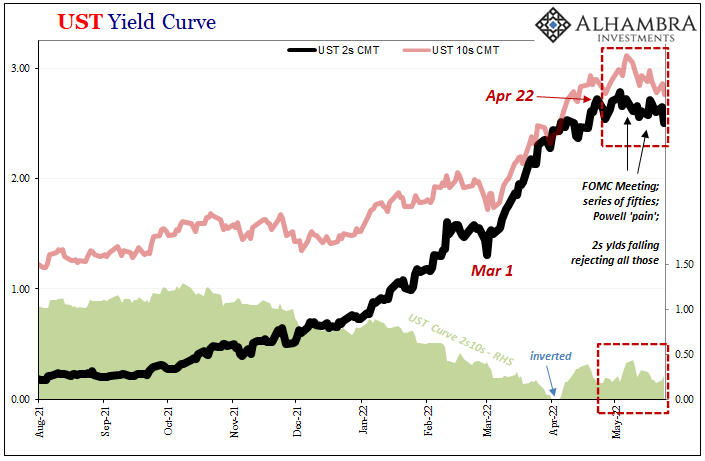

This particular relationship between UST curve and the Hong Kong index is murkier the wider the historical lookback, if only because the yield curve has itself flattened so much and at different intensities over the last decade and a half since Euro$ #1 – the original “somehow” Global Financial Crisis.

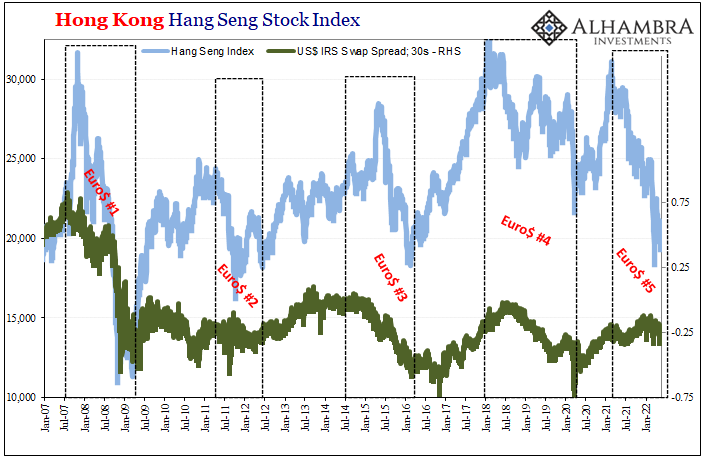

Dates still match overall, though, which we can better observe using instead one of our favorite dollar shortage indications: 30-year swap spreads. The swap spread, and difficulties revealed by it, is a toxic mixture of balance sheet constraint and collateral shortage all piled neatly into a single market spread (set against nominal UST yields, too).

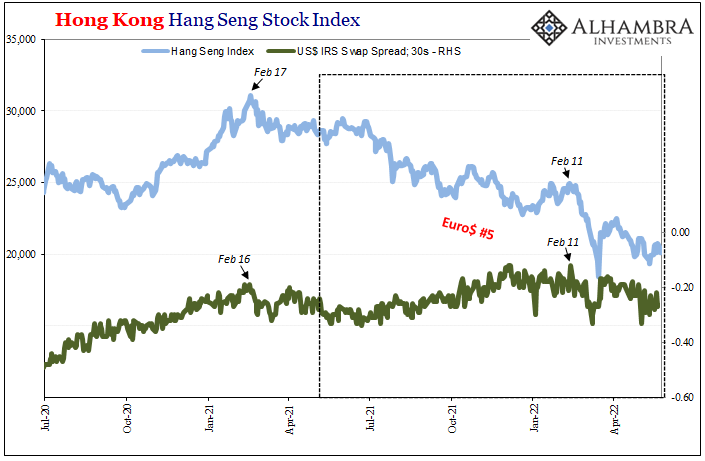

Never exact, yet there’s more than a passing relationship here. And given how it repeats every time, up to now five times, there’s no chance this is some random fluctuation.

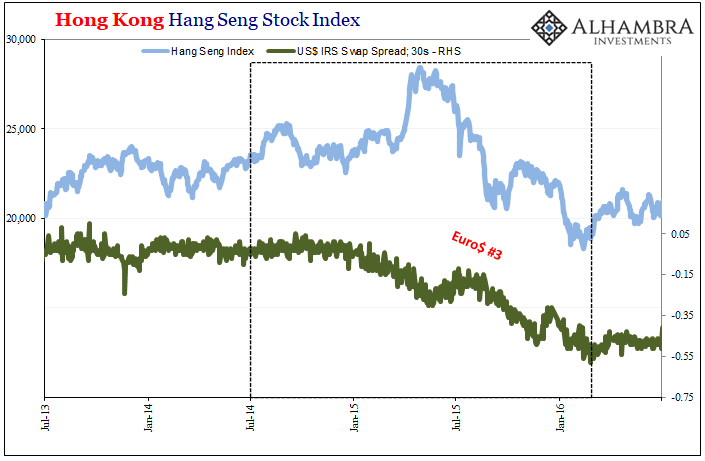

When you examine each instance individually, the relationship becomes even more compelling:

But what is “it” that connects eurodollar squeezes, these all-too-regular dollar shortage instances, with specifically Hong Kong equity markets?

It could be nothing more than sentiment; HK therefore China when highly susceptible to the same thing driving eurodollar (and collateral) scarcity. Repetition, though.

In my view, and you are, as always, free to make your own determination, there’s correspondent behavior behind all this (why the detailed opening). And if that is the case, it would mean something like contagion.

Again, I’m not saying 1929-style global contagion, or even 2007, rather what seems to be a financial/money mechanism whereby one problem gets passed into another systemic piece which only makes the problem worse for everyone participating in either. Since eurodollar, and eurodollar as global reserve, it’s a problem for everyone just starting to and from China.

So, with Hong Kong share prices, at least the Hang Seng, careening down toward values last seen in 2016, might this be telling us something about the true and more seriously negative potential of Euro$ #5?

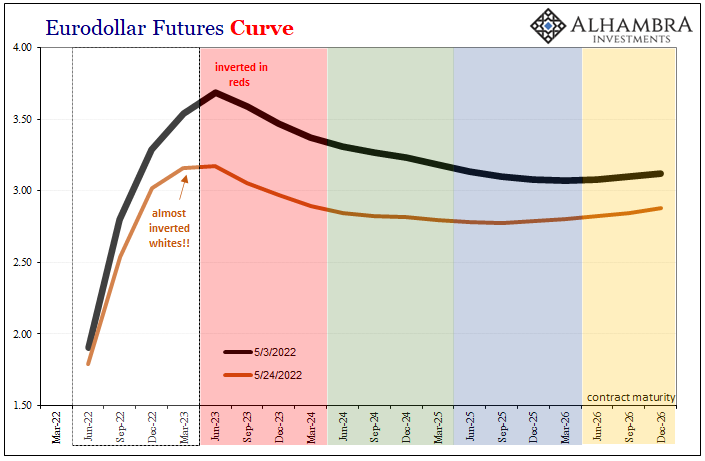

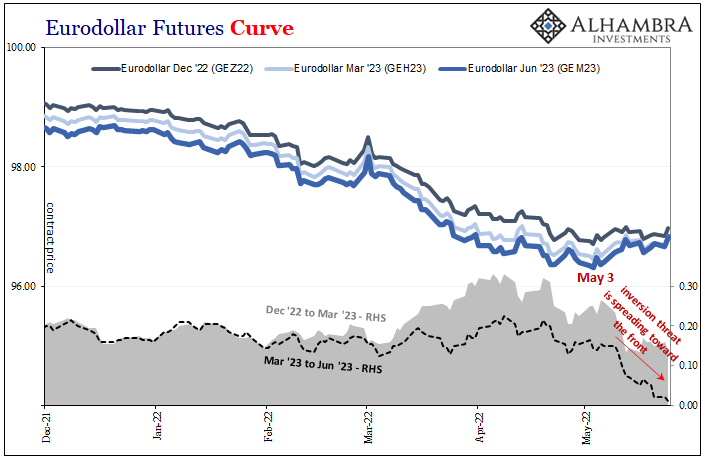

With eurodollar futures inversion nearing the whites, there’s obviously something very much amiss right now; certainly several things. Hong Kong connections wouldn’t explain everything, they might, however, represent deeper (kind of ancient) fault lines due from lingering systemic fragility. With an unhealthy dose of imperial Xi Jinping arrogance.

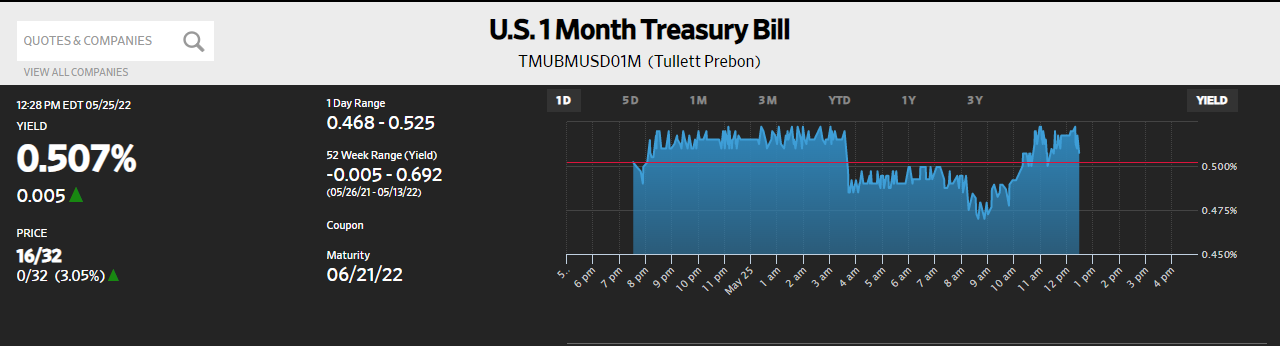

Further (not necessarily extreme) deflationary money potential. As if we didn’t already know it; yet another sizable and sustained scramble for collateral just this morning. From near the end of the Asian trading session.

Stay In Touch