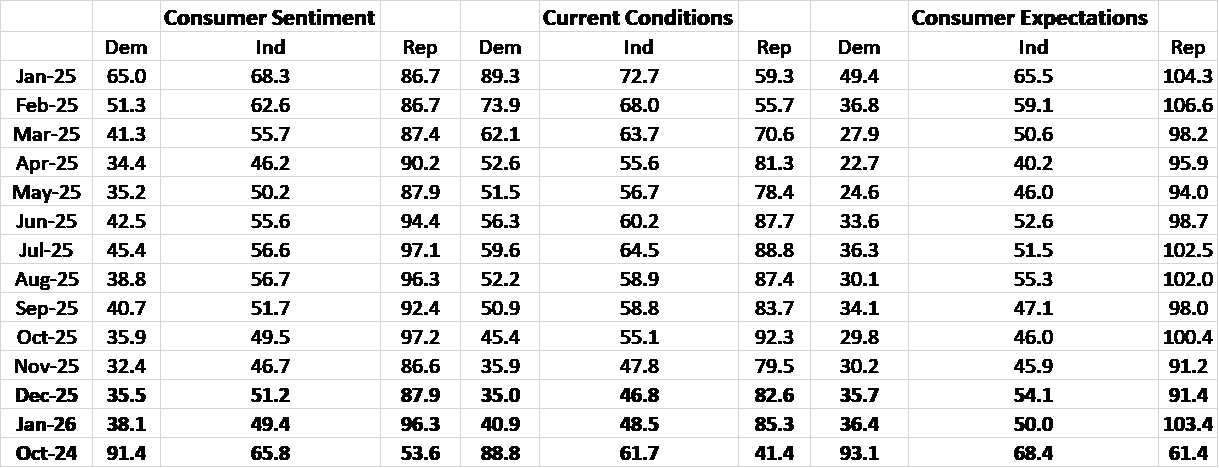

As we near the end of the first year of President Trump’s second presidential term, the debate about his economic policies hasn’t changed much. That’s because it isn’t an economic debate mostly, but a political one and that applies to the public as well as economists (yes, they are as vulnerable to political bias as anyone else). Democrats hate Trump’s policies and think the economy is awful. Independents approve slightly more than Democrats. Republicans think things are wonderful and will only get better. You can see the divide in the University of Michigan consumer sentiment poll, which conveniently breaks down their survey by political identification (self):

I’ve included the readings from October of 2024 for comparison purposes and you can see that Democrats’ and Republicans’ opinion of the economy is highly dependent on who occupies the White House. Independents are more consistent and probably offer a more honest view of the economy, which has deteriorated somewhat over the last year.

The debate among economists only appears more sophisticated because they adorn their arguments with data. Of course, there’s a reason everyone knows the phrase “Lies, damned lies and statistics” and that applies to economic statistics more than most. If you doubt the political nature of the debate, consider that 15 years ago there wasn’t one Republican economist (or politician for that matter) who would have had anything good to say about tariffs. Protectionism was a purely Democratic talking point then but today the roles have reversed, with numerous Democrats taking the anti side while Republicans have a new found respect for the policy (or fear of President Trump).

I am not immune to political bias – I instinctively dislike and distrust all politicians – but as an investor, especially an investor of other’s money, I have an obligation to see things as clearly as possible. I mostly use markets to determine the current state of the economy but I also review the economic data, aware that most of it is just noise on a month-to-month basis. If you want to get a sense of the economy, you need to look at trends over longer periods of time and compare them with history. I don’t spend a lot of time speculating about the future because it is impossible to predict and attempting to do so can lead to big investing mistakes. Usually, one has time to adjust to changes in the economy but you should have a strategic investment approach that will allow you to ride out any changes if you can’t. If your “strategy” depends on you or your surrogate predicting the future economy and making changes to your portfolio based on those predictions, you will almost certainly do worse than just buying and holding one strategic allocation come hell or high water. There are times to make tactical allocation changes to your portfolio but they are infrequent and should be small and incremental.

The simplest way to judge the current state of the economy is to review the two most important market indicators – interest rates and the trend of the dollar.

Interest Rates

Changes in the interest rate complex since the late 2024 election have been very modest. Rates rose early in the year on optimism about the Trump administration’s policies but fell back when they proved quite a bit more aggressive than his first term. The “liberation day” tariff announcement drove long and short-term rates down, a rapid and large reduction in growth expectations. This could also be seen in real rates, which also fell, and in credit spreads, which blew out by almost 200 basis points in a matter of days. The slowdown scare eased as the administration backed off the implementation of the tariffs.

Markets have calmed considerably since last April as investors have become accustomed to President Trump’s negotiating style and current expectations are almost exactly the same as they were prior to his election. One could argue that expectations would be worse – and rates lower – absent the surge in AI spending and its potential impact on future productivity but I see little to be gained from that argument. It is, in any case, impossible to quantify any such effect. In the end, it doesn’t matter why rates are where they are; it is sufficient to know that growth and inflation expectations have changed very little over the last 14 months and are in line with long-term averages and norms.

The 10-year Treasury rate is a proxy for market expectations for NGDP growth (NGDP = real growth + inflation). Right after the election in late 2024, the 10-year Treasury rate stood at 4.42%, rose to its 2026 high on January 10th at 4.79%, fell to its low on October 22nd at 3.97% and today stands at 4.19%. Market expectations for NGDP growth have changed little since the election but have fallen more significantly since the peak in early January when we started to get a clearer picture of the policies to come. Overall, though, despite a lot of turmoil over the last year, the outlook has changed very little. Longer term, the current 10-year rate is right at the average since 1990.

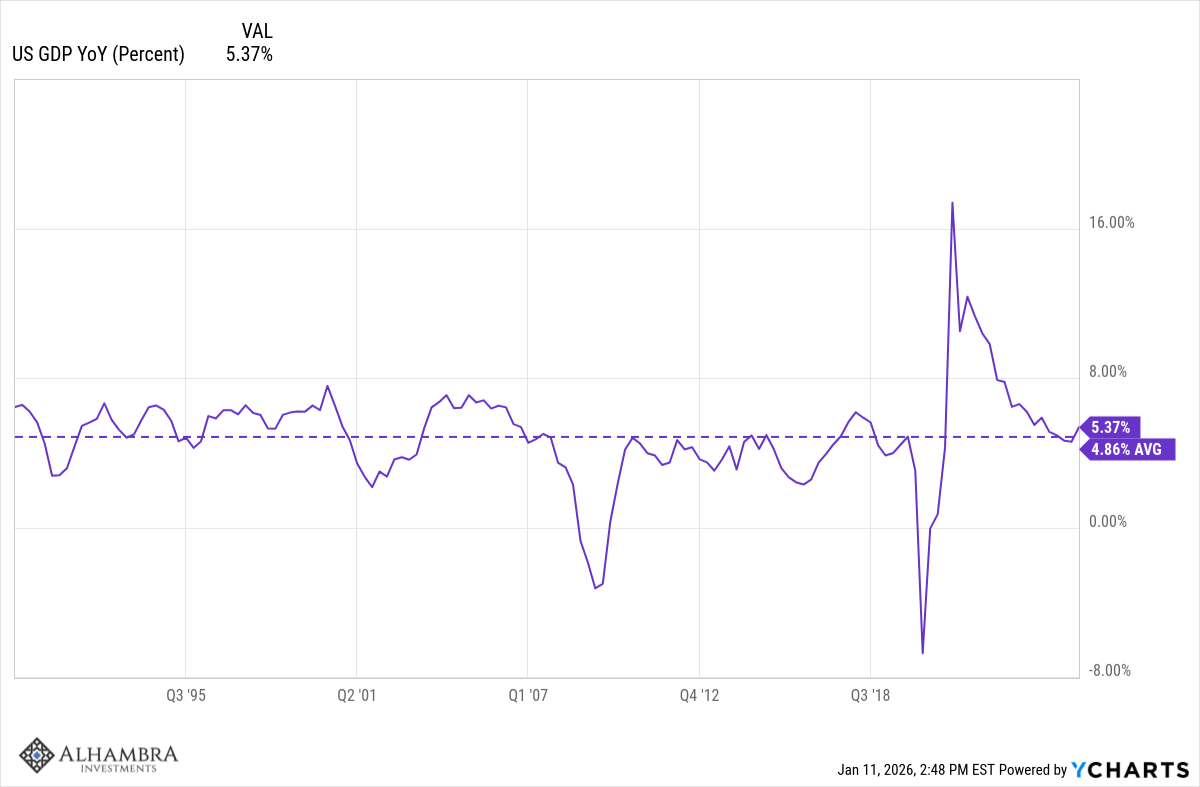

The current year-over-year change in NGDP is 5.37%, a little above the long-term average of 4.86%. Since the 10-year yield and the year-over-year change in NGDP tend to converge, we would expect either a mild slowing of the economy or a rise in the 10-year rate over the next year. The best case scenario from an economic growth point of view would be a slight rise in rates and a steeper yield curve.

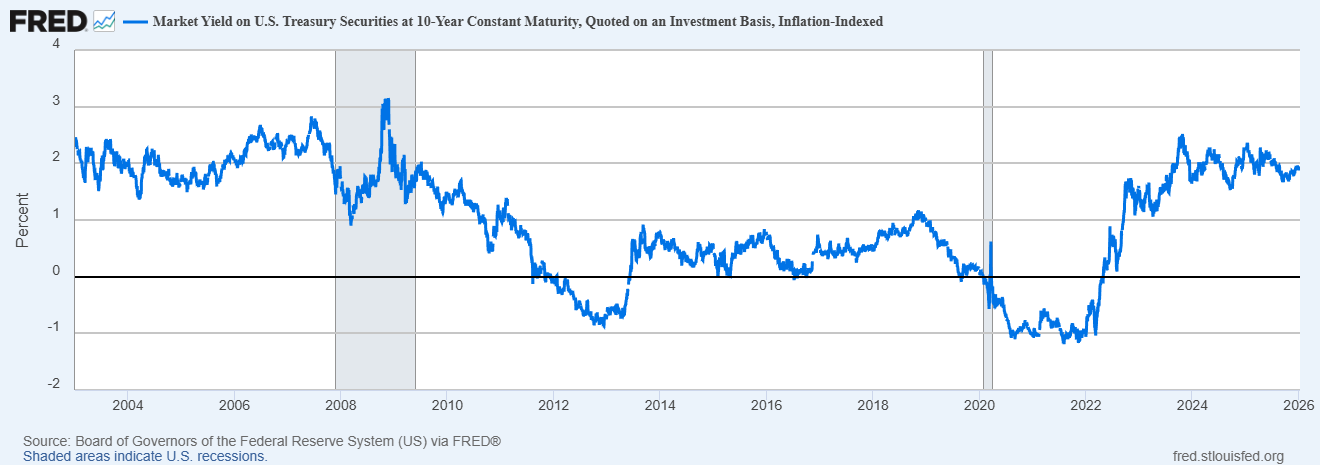

Real interest rates have also changed very little since the election, falling from 2.04% to today’s 1.92%. They are also in line with real rates that prevailed before the 2008 financial crisis:

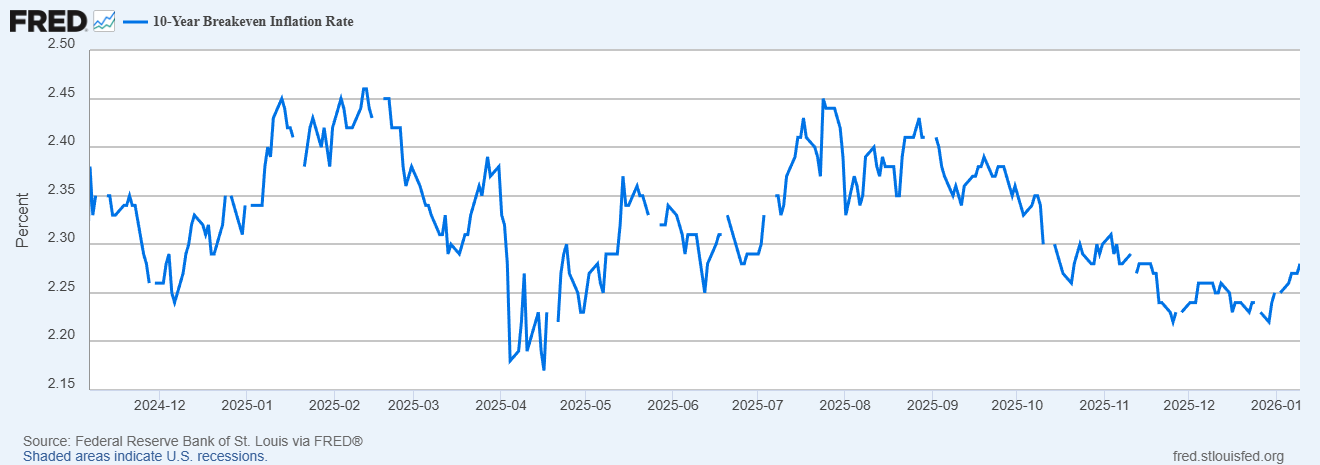

Since the nominal 10-year rate fell slightly more than the real rate since the election, inflation expectations have fallen very slightly:

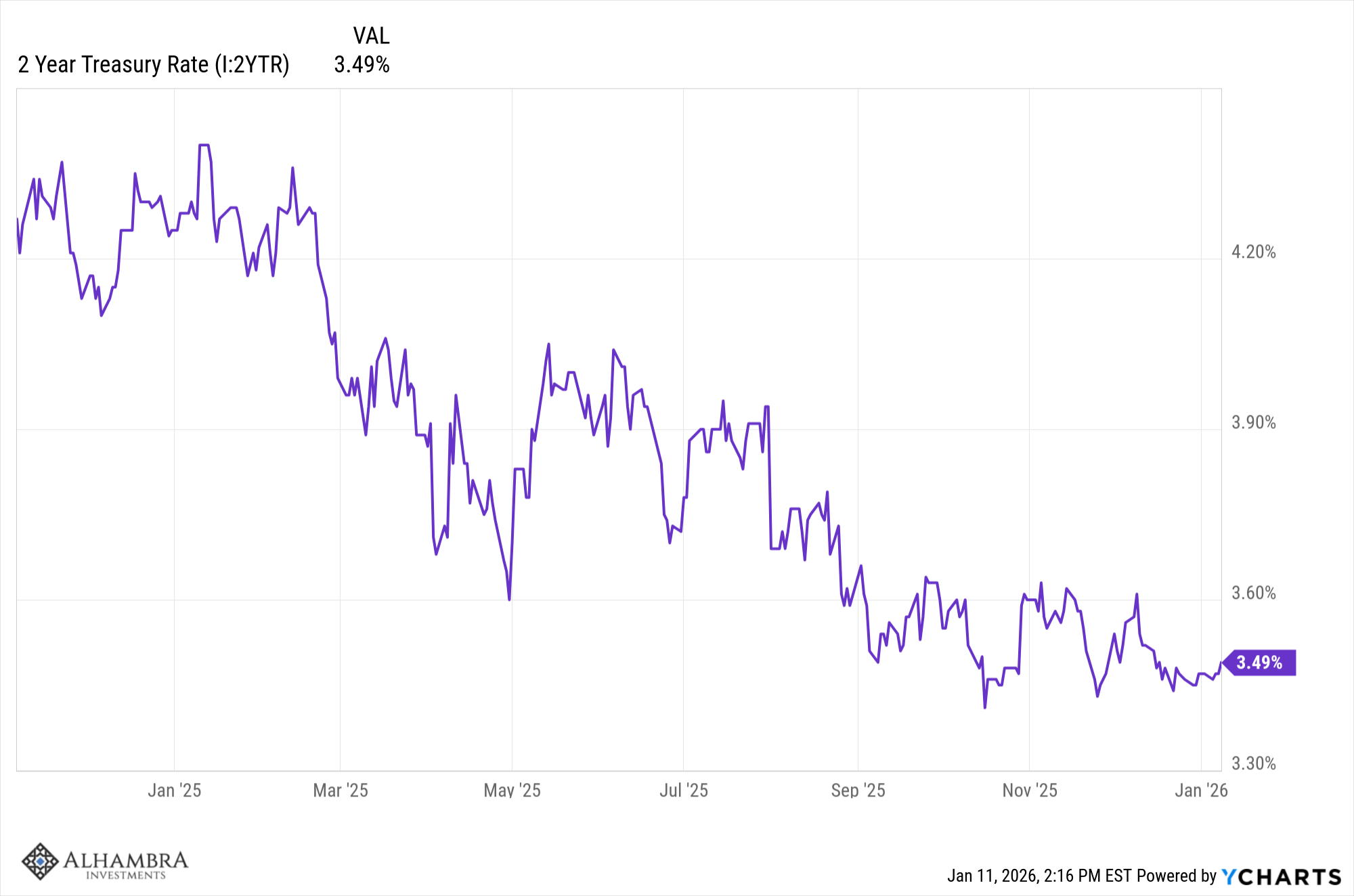

Shorter term interest rates have also fallen since the election, much more than long-term rates:

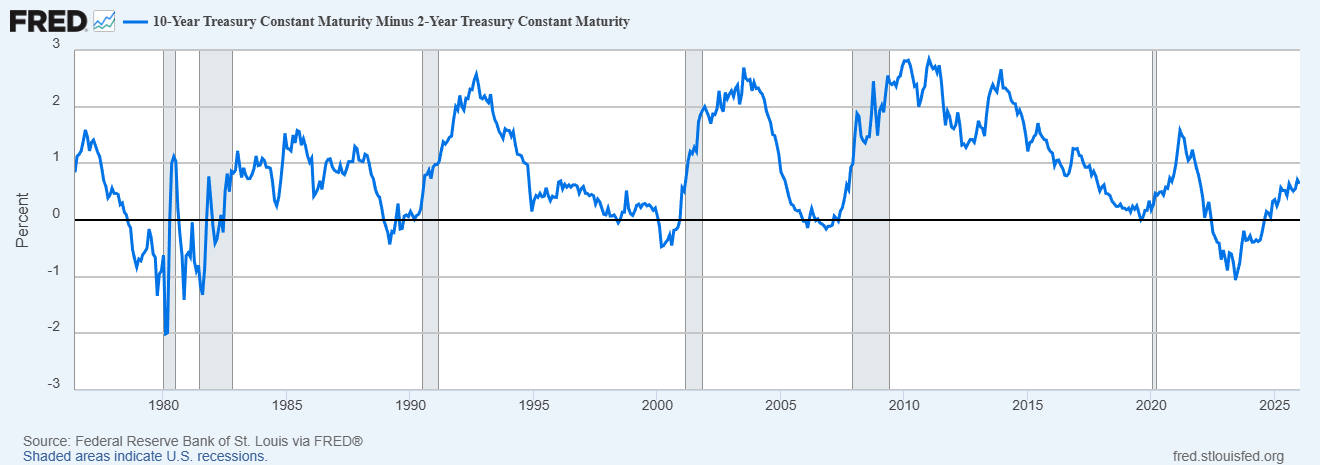

The drop in short-term rates reflects the market’s expectations for Federal Reserve interest rate cuts. There were 3 cuts in 2025 – in September, October and December – of 1/4 point each. Expectations right now are for one or two more cuts in 2026 but based on current pricing in the futures market, it isn’t a strongly held opinion. Highest odds for a cut are for the first one of 2026 at the June meeting but it is less than a 50% chance. There is about a 33% chance of a cut in the fall. The larger fall in short-term rates so far means the yield curve – the difference between long and short rates – has steepened:

This steepening, where short-term rates fall faster than long term rates, is known as a bull steepener and is often associated with the onset of recession. However, the steepening before recession is usually very rapid as short-term rates price in an aggressive Fed easing cycle. That isn’t what’s happening now. In general, a steeper curve is associated with better growth a year hence with peak growth expectations coming when the curve hits its steepest point. As you can see the curve is not currently anywhere near its past peak steepness and argues for continued modest growth with a slight upward bias.

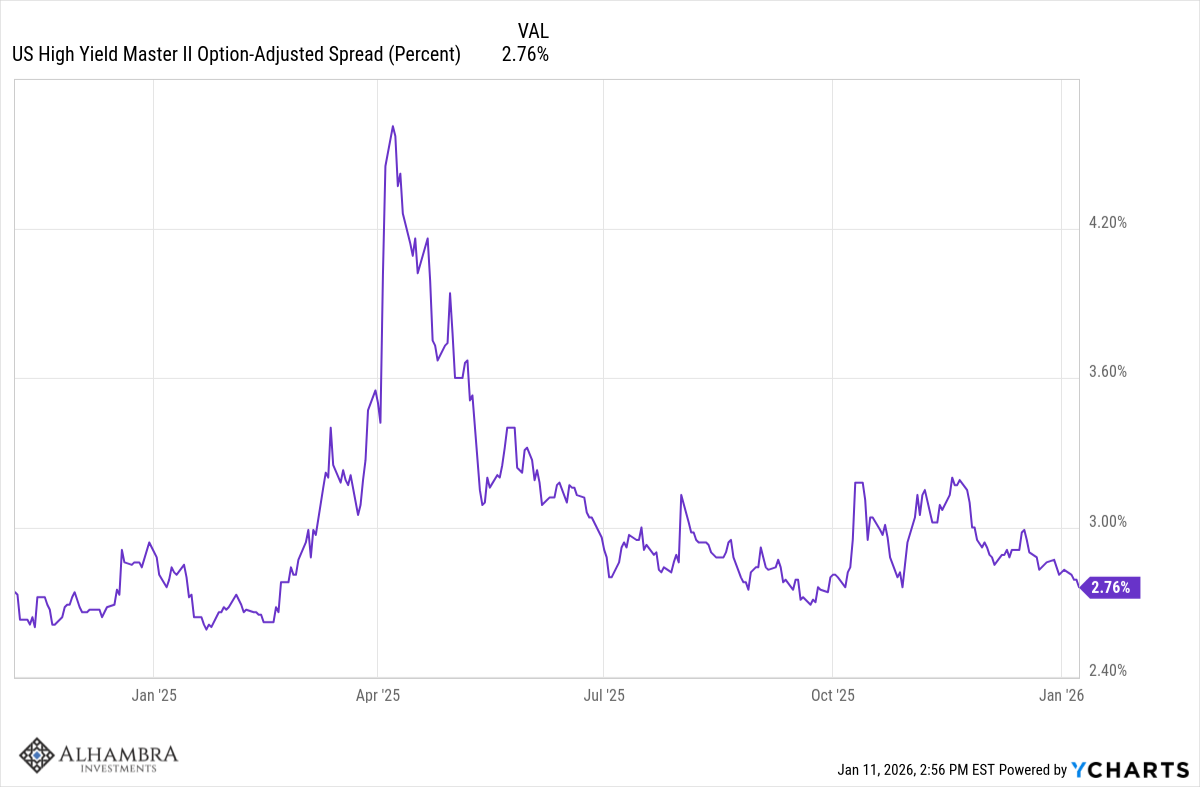

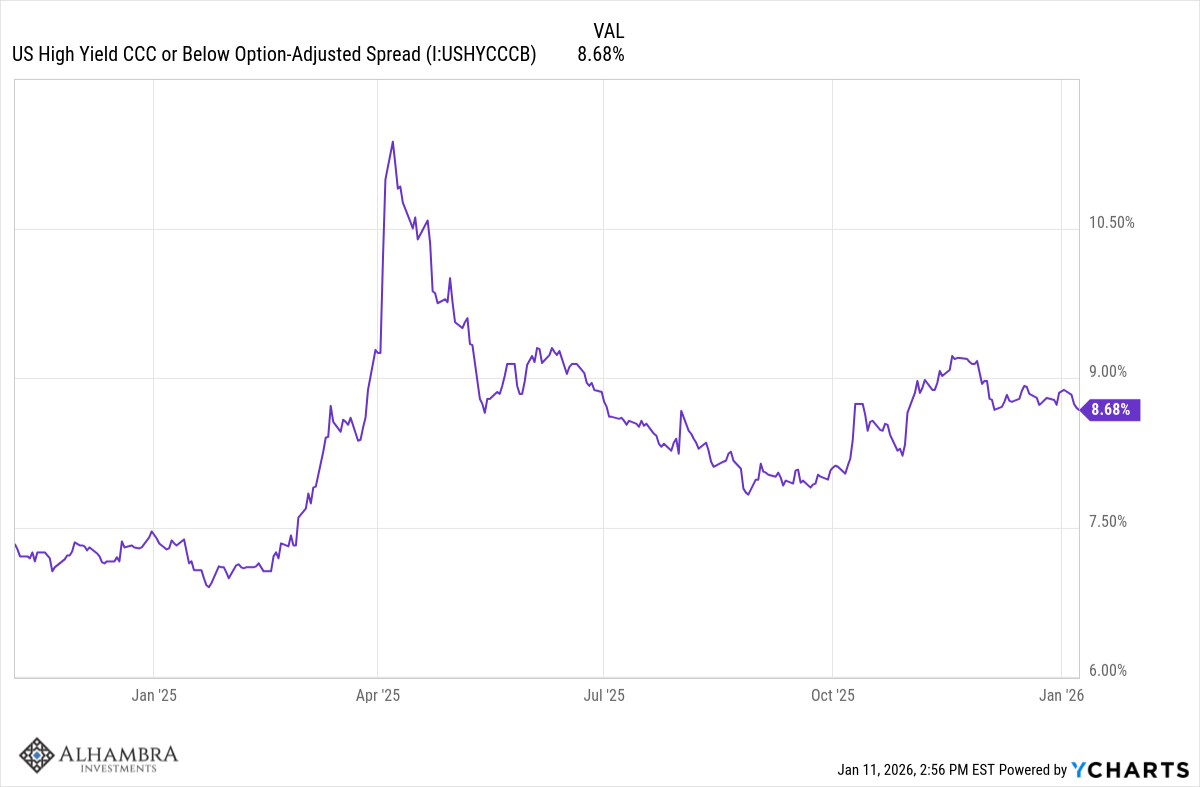

In corporate bonds, credit spreads for junk rated debt are unchanged since the election although there has been some widening in lower rated bonds (CCC):

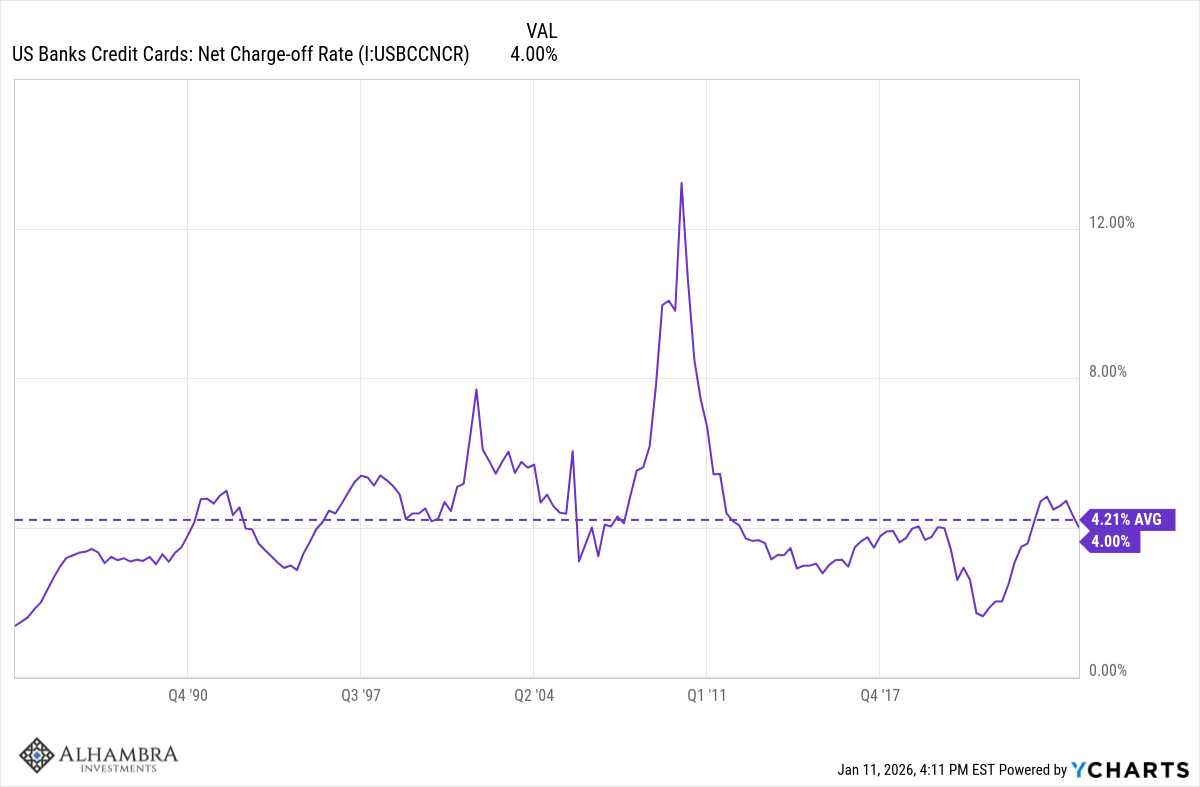

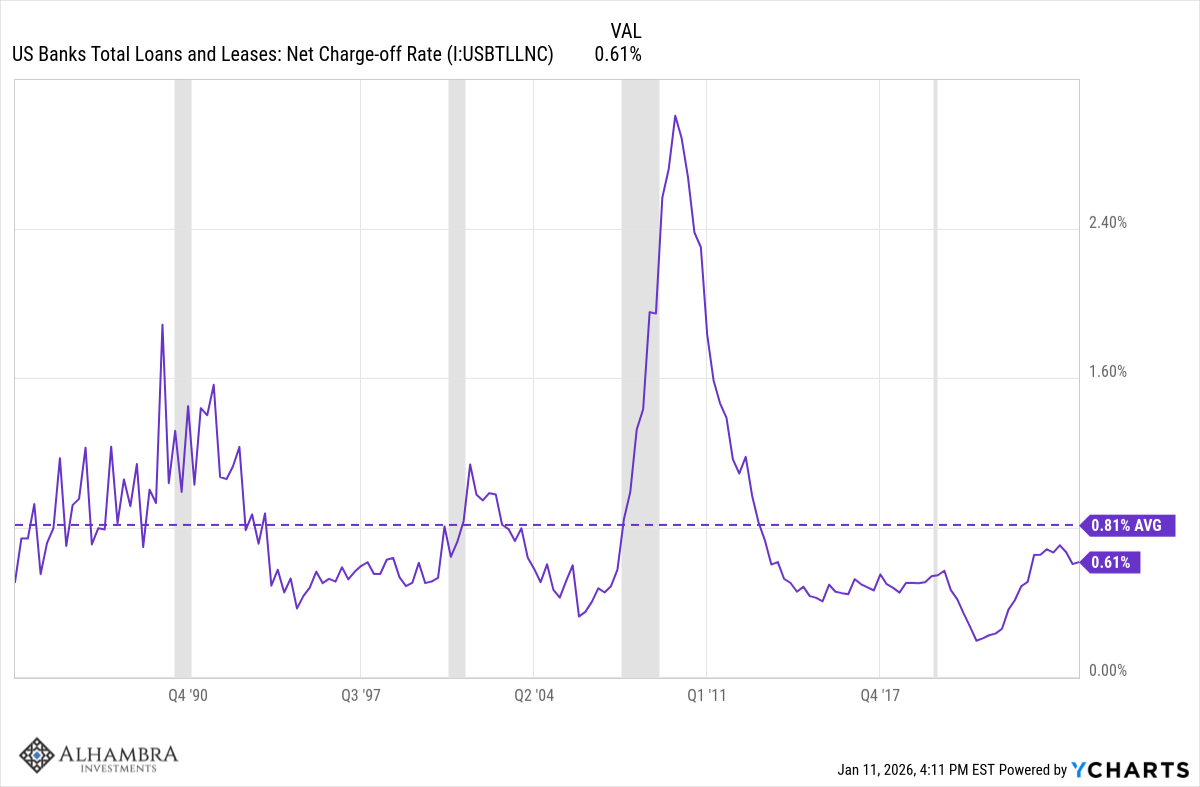

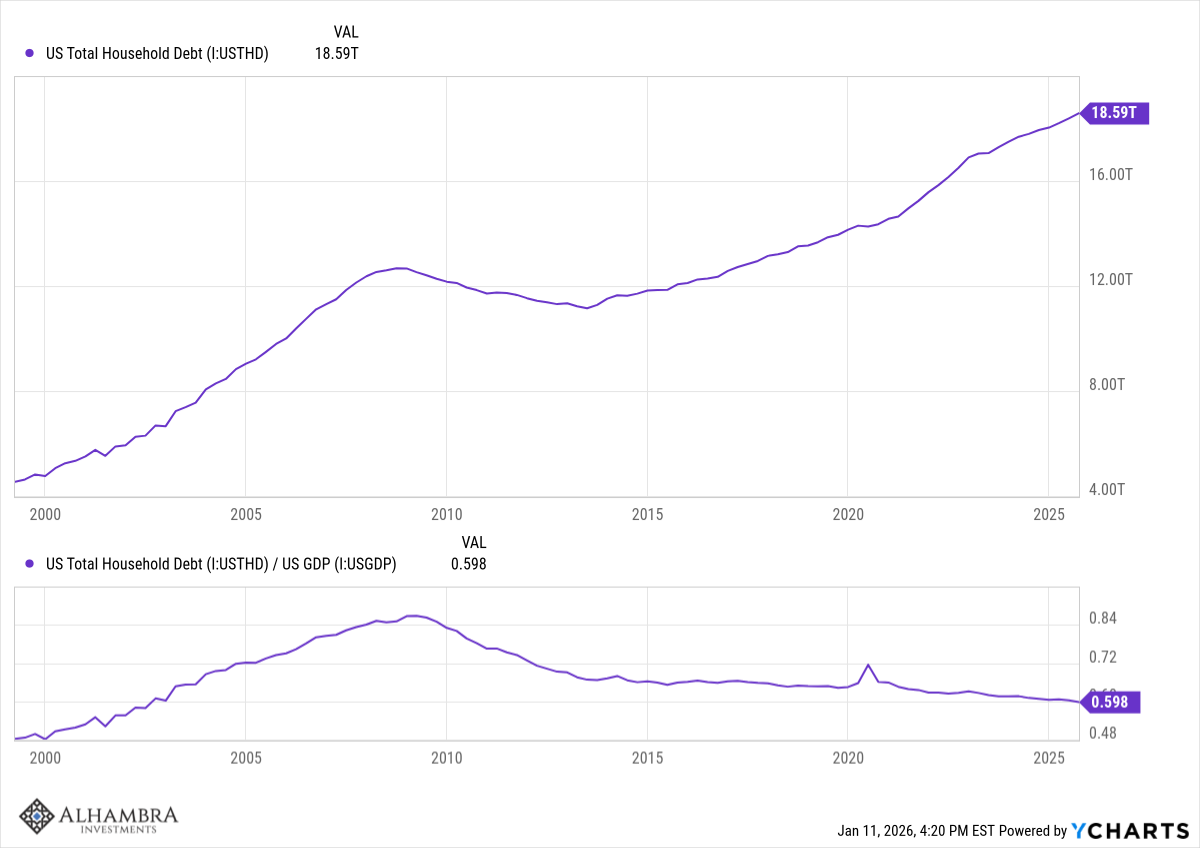

Credit markets are generally healthy and despite some chatter about households having trouble paying the bills, loan charge-offs actually improved in the first half of the year. Household debt as a percent of GDP continues to fall.

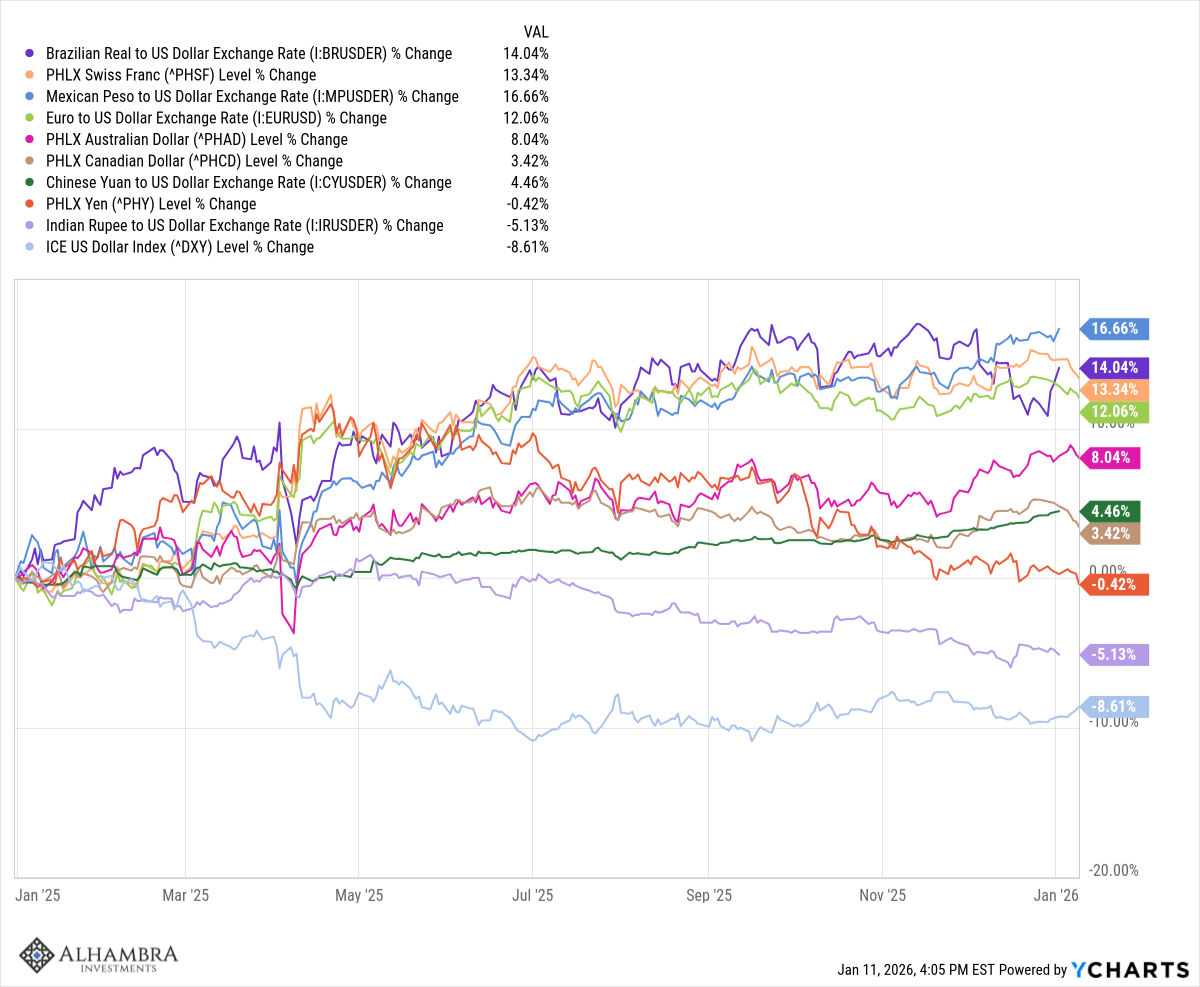

US Dollar

The change in the dollar generally tells us about the change in relative growth expectations between the US and the rest of the world. This is where we see the biggest impact from President Trump’s tariff barrage. The dollar index is down nearly 10% since peaking last January 10th, an indication that growth expectations for the US have fallen relative to its biggest trading partners. The DXY would be down more but for a 14% weight in the Japanese Yen, which is mostly unchanged versus the dollar this year. The Euro, however, is up 12% against the buck. The emerging market index is down less – about 6.5% – but Latin American currencies have done particularly well with the Brazilian real up over 14% and the Mexican Peso up 16%.

This devaluation of the dollar is not what was expected at the beginning of the year or by the textbooks on tariffs. The textbook says that the countries on which tariffs are imposed will see their currency devalue to offset the impact of the tariffs and that is what Treasury Secretary Bessent and Stephen Miran predicted. That expectation is based on past experience and a dash of common sense, but the response to Trump’s tariffs has been quite a bit different than in past trade wars. Generally, we expect the countries on which tariffs are imposed to retaliate and impose tariffs on their adversary’s goods. But in this case, the retaliation didn’t happen. Why would that cause the dollar to fall? Well, in the long run we know that tariffs are negative for growth – for the country imposing them. If the other countries don’t retaliate, the delta, the change in relative growth between the two countries moves against the US and the dollar.

Most of the focus since the imposition of Trump’s tariffs has been on the effect on prices. Economists of all kinds have mischaracterized this as a discussion about inflation but that is, as I pointed out several times last year, plain wrong. In the short term, tariffs will raise the price of the goods being tariffed but absent a change in monetary policy, prices of other goods not being tariffed should fall and inflation shouldn’t change. The long run may be a different story but it still has to do with monetary policy. If tariffs reduce the capacity of the US economy by making us less productive, then tariffs could be inflationary. But that assumes that monetary policy doesn’t change.

If 5% NGDP growth produces 2.5% real growth and 2.5% inflation today but tariffs reduce the capacity of the economy, then 5% NGDP growth might produce 1% real growth and 4% inflation. To reduce inflation, the central bank would have to reduce NGDP growth. The problem is that getting inflation down to the target would likely cause a recession which is why it is so hard to kill inflation. Most people would prefer growth and higher inflation to contraction and lower inflation.

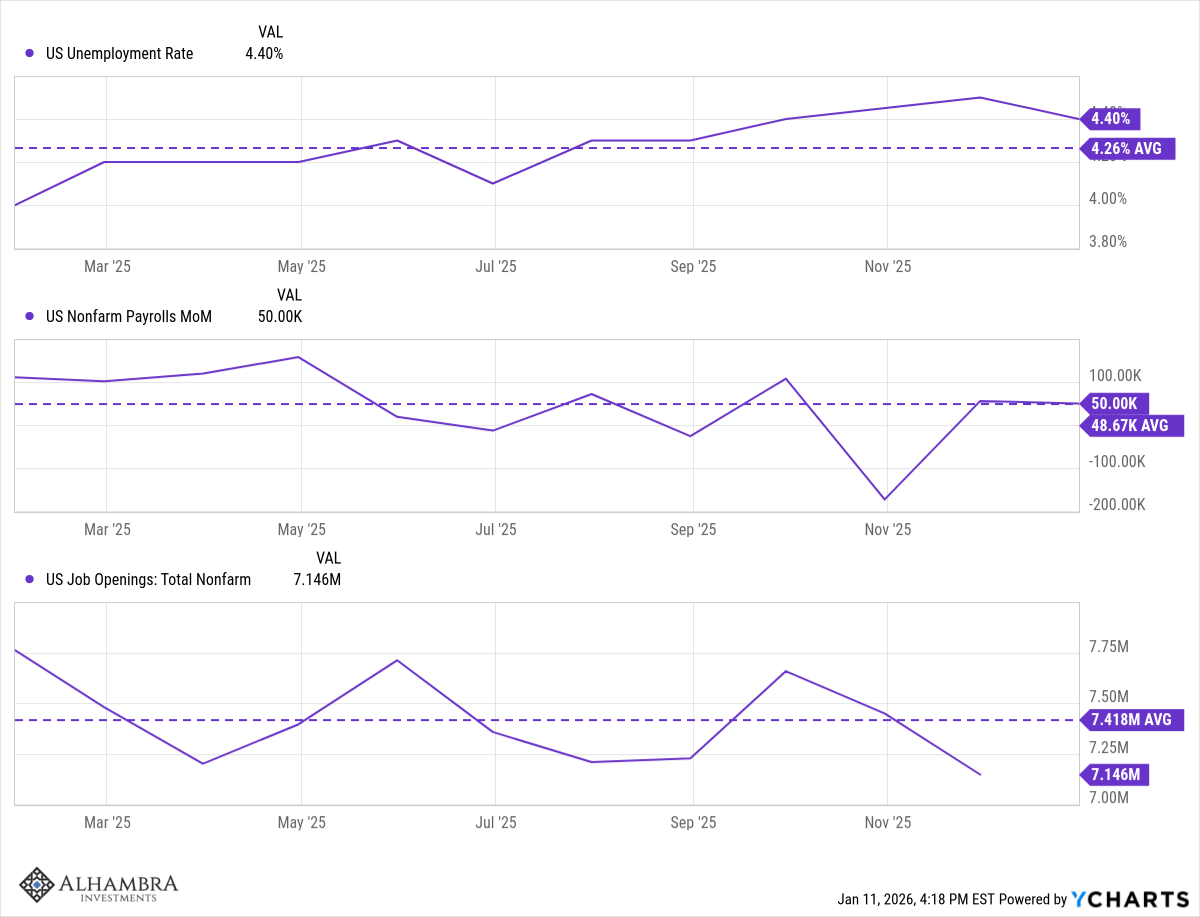

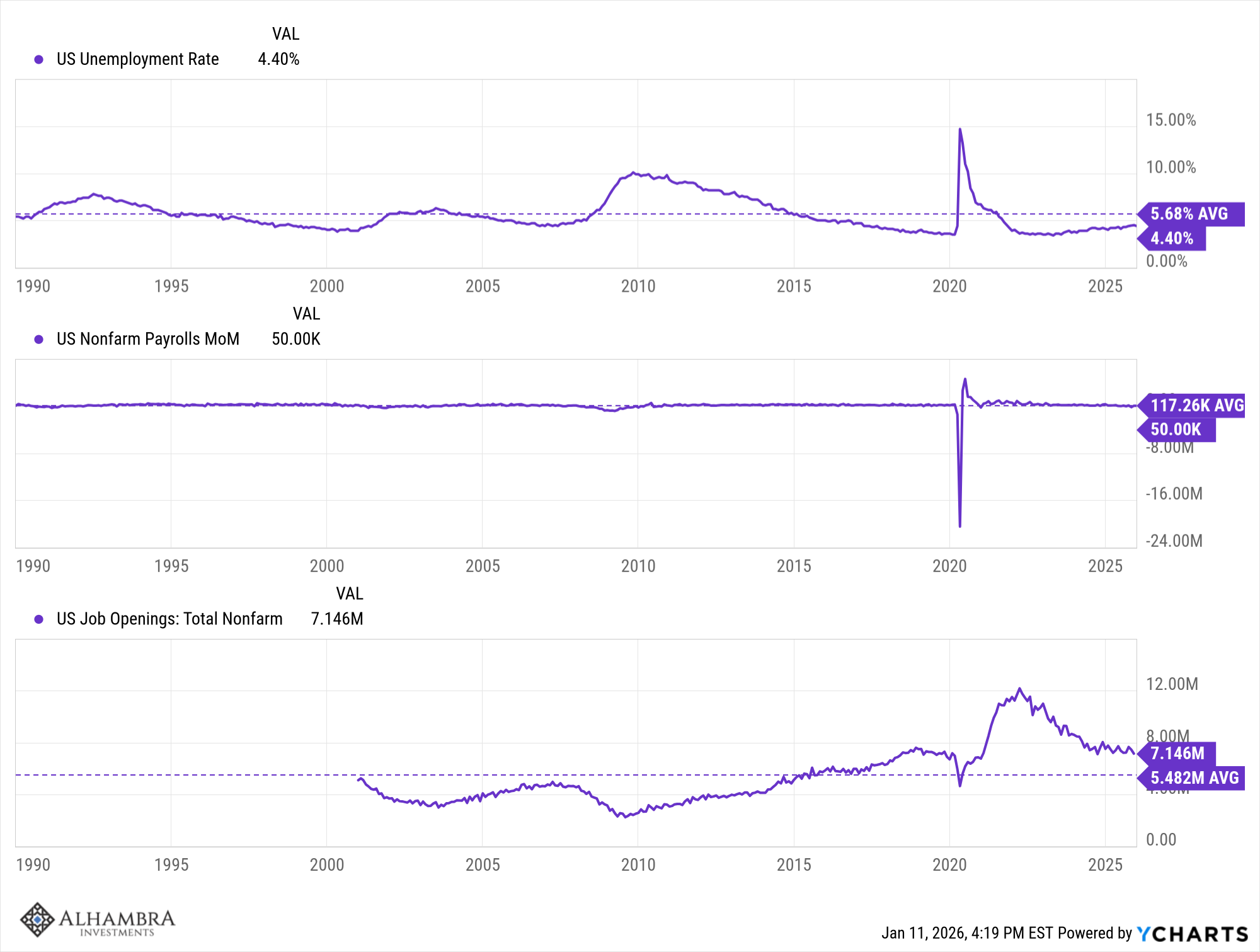

There has been little focus on the growth implications of tariffs so far because the negative growth effects have been, so far, quite localized and not large enough to affect the national aggregates. We have seen a slowdown in the labor market over the last year but so far it isn’t big enough to warrant much concern. The unemployment rate is up, monthly payrolls have averaged just 50k per month (vs 117k long term average) and job openings have fallen. But compared to long-term averages, the labor market still looks pretty good:

Over the last year

Since 1990

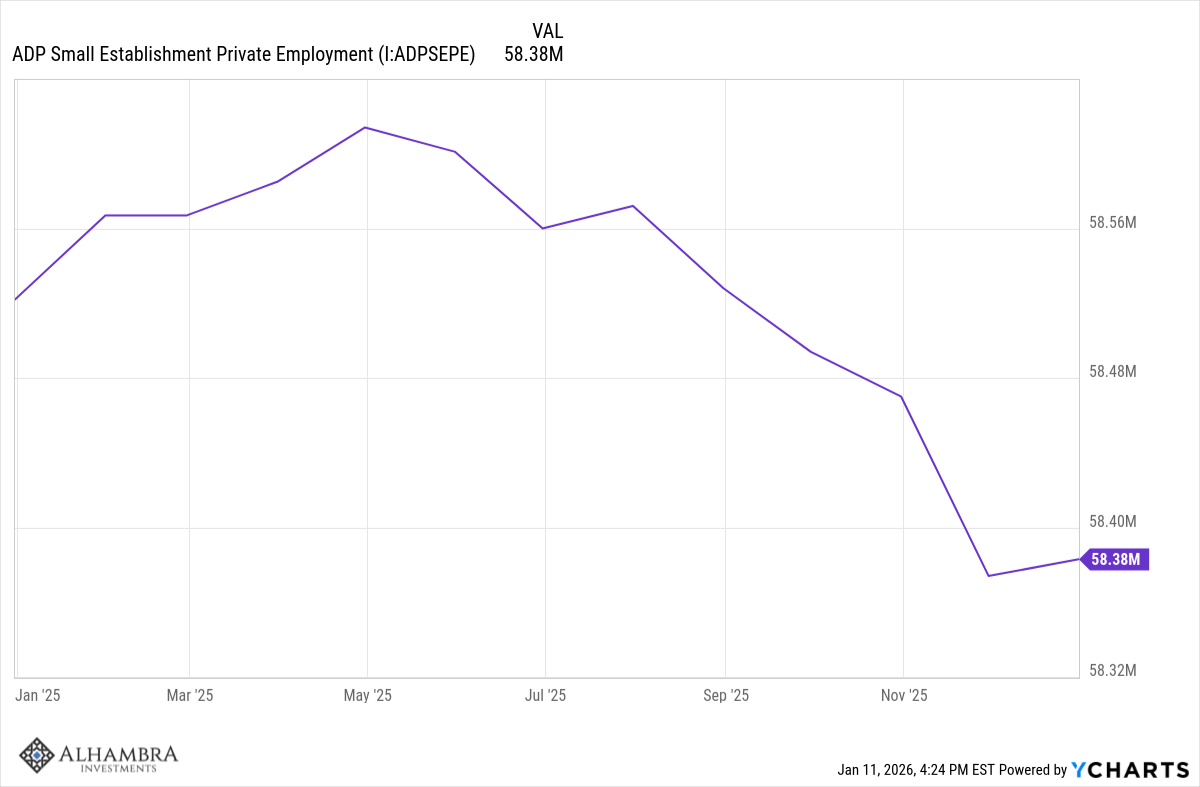

A lot of the change in employment happened in the small business sector. That’s something I warned about last year with regard to tariffs; small companies have a much harder time coping with tariffs than large, well-funded companies. Notice that small companies started to shed jobs right after “liberation day” which was nothing of the sort for them.

.

.

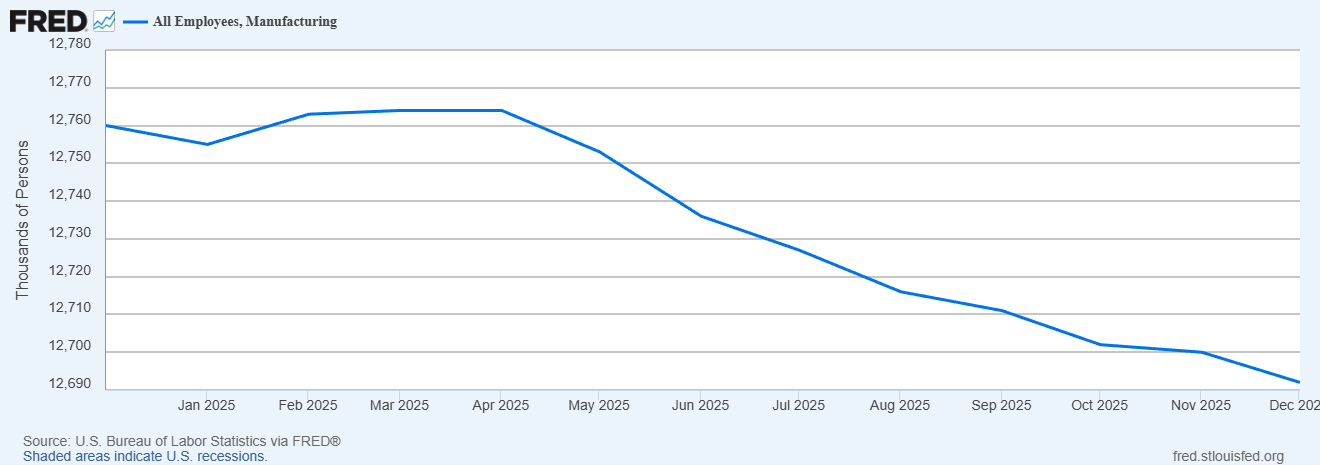

It should also be pointed out that while President Trump believes tariffs will revive manufacturing, so far it isn’t working and in fact may be doing the opposite. The only caveat is that it is still too early to know how this plays out over the long term.

I’ll close with two more charts, one potentially negative and one potentially positive.

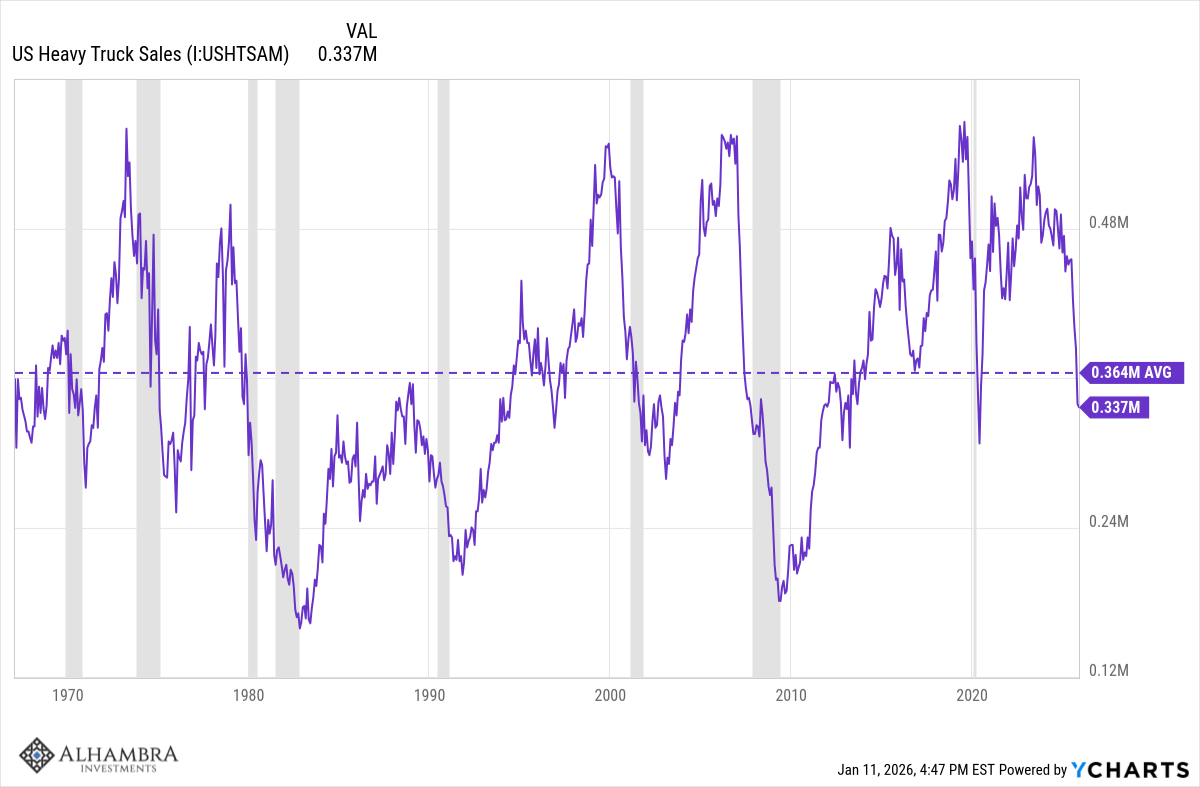

This is heavy truck sales, which has been a great recession indicator in the past. As you can see, sales have taken a dive recently and are now below the long term average.

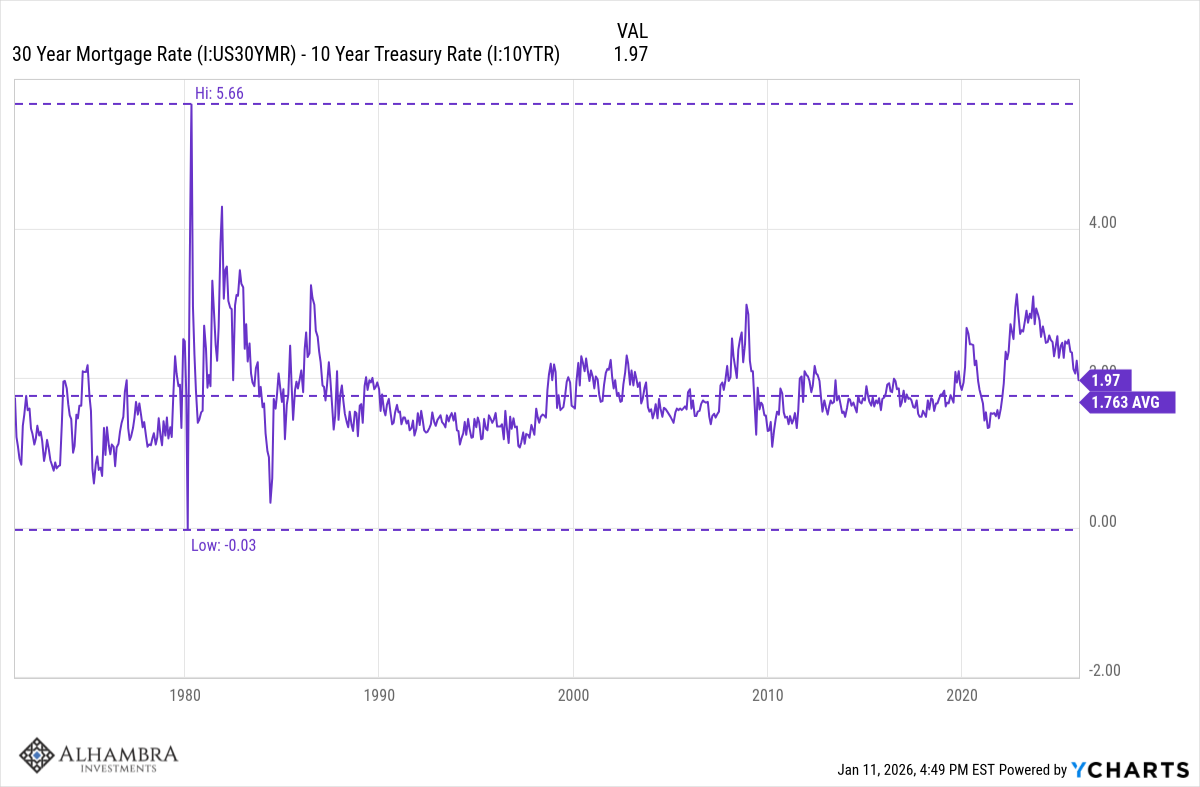

And this is a chart of the 30-year mortgage rate versus the 10-year Treasury rate. You might remember I highlighted this repeatedly last year because it was much wider than the long-term average. As the spread has come down, so have mortgage rates. And it is starting to have an impact on the real estate market. I’ll write more about that in coming weeks.

The economy right now is not significantly different than it was before President Trump was elected. If that surprises you, in either direction, you probably need to stop thinking about the economy in political terms. I have said many times that people over-estimate the impact politicians have on the economy; if last year doesn’t prove that, I don’t know what does. President Trump and his administration made big changes – both sides believe that – but the outcome wasn’t much change, at least for now. A warning though – there are only two things that create economic growth. Workforce growth and productivity growth. The President’s immigration policy is a negative for the former and his tariffs are negative for the latter. What we don’t know is how long and how big. One year is certainly not long enough and the impact so far is negligible. If that changes, the markets will tell us.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch