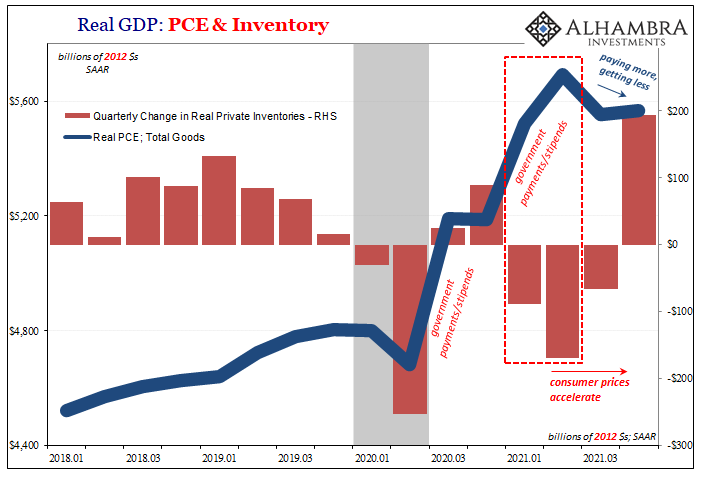

The goods economy in the United States is – maybe was – the lone economic bright spot. That in and of itself should’ve provoked more caution, instead there was the red-hot recovery to sell under the cover of supply shock pricing changes. The sheer spending on goods, and how they arrived, each unabashedly artificial from the get-go.

Combine those two factors, however, the necessary supply squeeze surge in prices along with the artificiality behind it wearing off, eventually perhaps inevitably the world’s lone bright spot would have to dim. Maybe the real question(s) always was (were), OK, slow, by how much (and how fast)?

Here lies the intersection between sales, inventory, and demand destruction created by consumer exhaustion in all its dastardly forms. Paying more for gasoline. Higher grocery tickets. Maybe a labor market that everyone says is short of workers yet doesn’t seem like it for too many barely hanging on in or just outside of it.

I think I heard this somewhere. https://t.co/aLCVfKi5eh pic.twitter.com/kPumM5WvLi

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) April 18, 2022

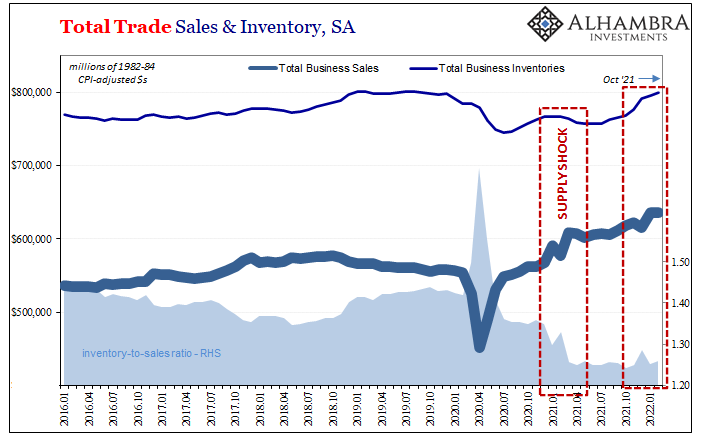

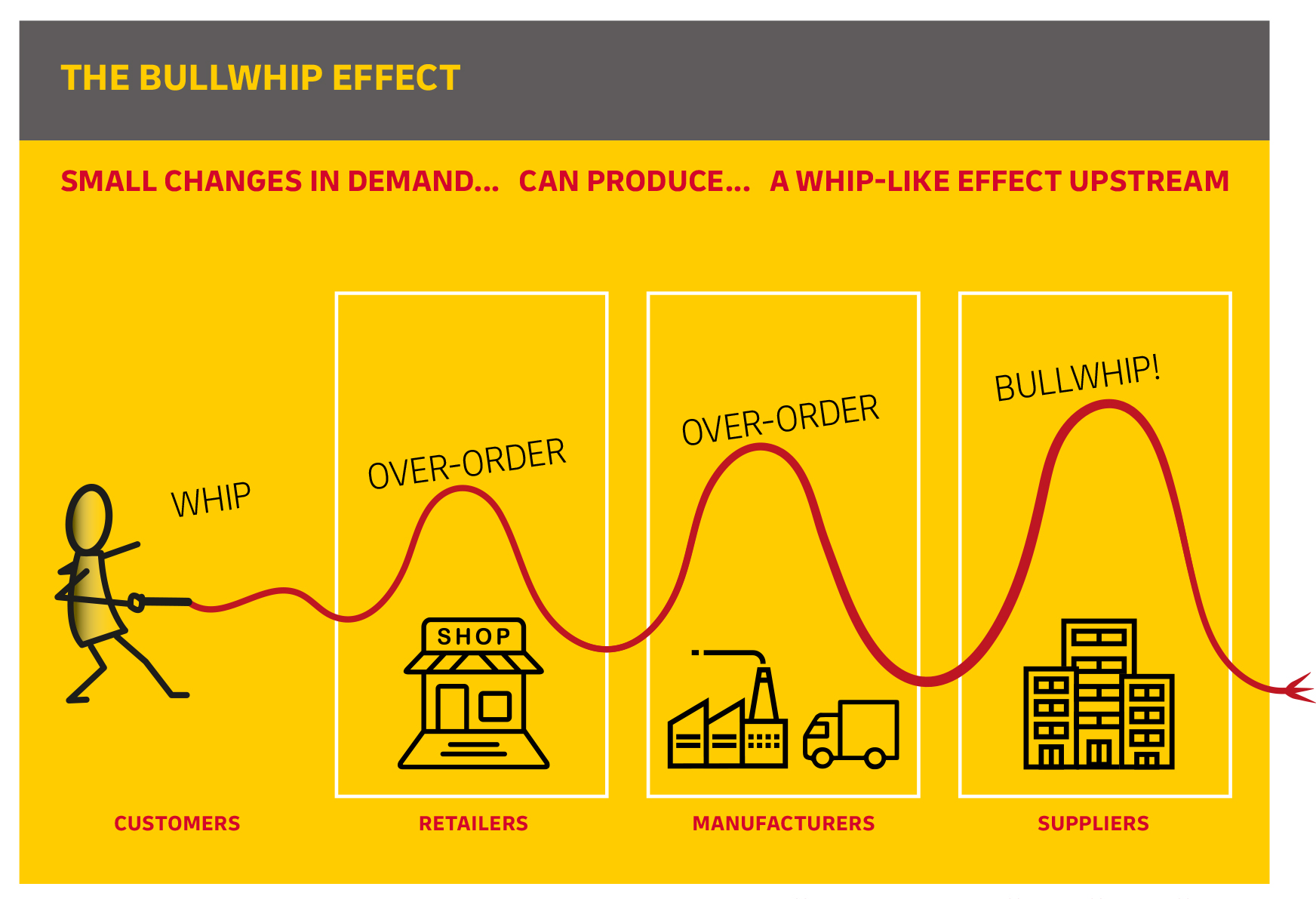

Since October, the rise of inventory in relation to potentially softening sales across the entire supply chain – even if still upwards near historic levels – puts the entire global goods economy in line of a hair trigger firing squad. Pumped up on both Uncle Sam along with mainstream Economist inflationary predictions and forecasts, small deviations from those might rapidly transcend the usual mechanical, cyclical downward swing.

One company already believes this has begun, and it has quickly progressed to compare as unfavorably as the last time the economy went through such a downturn (Euro$ #4 just three years ago).

FreightWaves’ view of the market has become clearer, and the picture isn’t pretty. We think another sharp, painful downturn in the U.S. truckload market is imminent, and it could be as bad as 2019…March is typically a strong month for trucking, as shippers start to stock their shelves in preparation for summer. And late March normally gets a reliable end-of-quarter boost in volumes as shippers pump sales and reduce inventories. This year, we are not seeing that surge. In fact, March volumes are softer than at any point in 2021 (other than holidays).

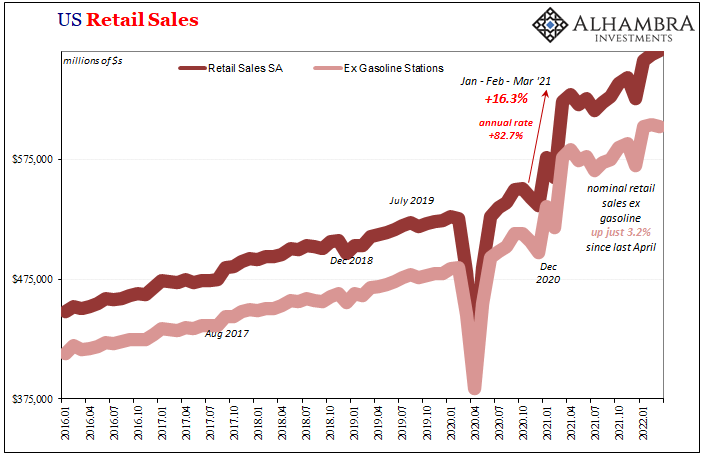

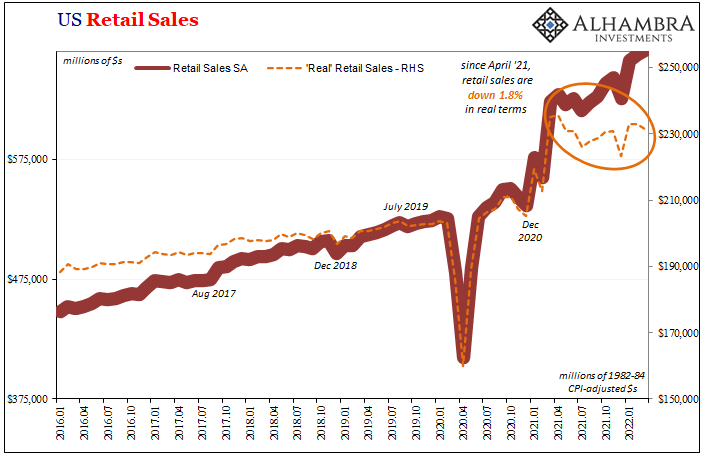

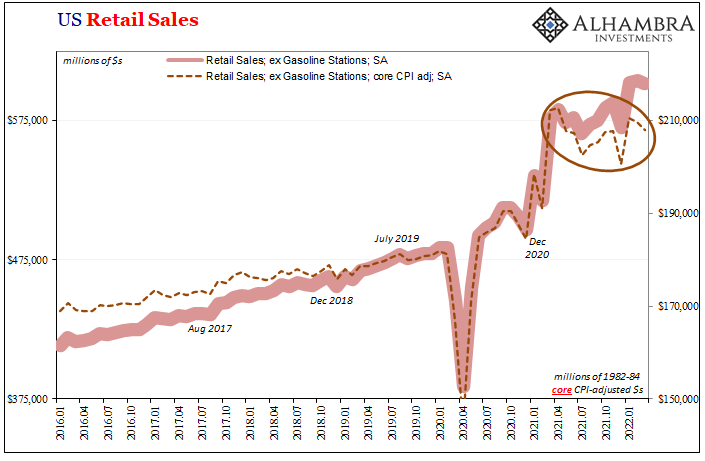

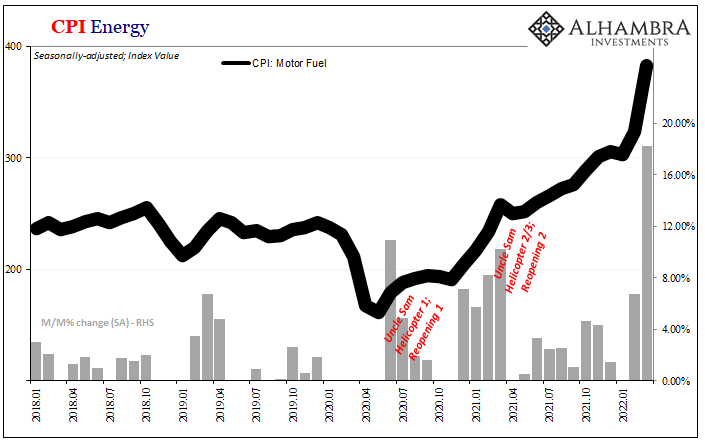

According to the US Census Bureau last week, retail sales remained elevated but only modestly when compared with most of last year. Furthermore, overall sales have been boosted largely by those of gasoline as well as overall prices (including the price of gasoline). Accounting for one or both, again, sales are high relative to pre-helicopter days but heading lower since them.

Using the CPI to deflate the estimates, seasonally-adjusted retail sales in March 2022 were down 1.6% year-over-year, and lower by 1.8% compared with April 2021. Excluding retail sales recorded by gasoline stations, the numbers are slightly worse (-2.2% since last April).

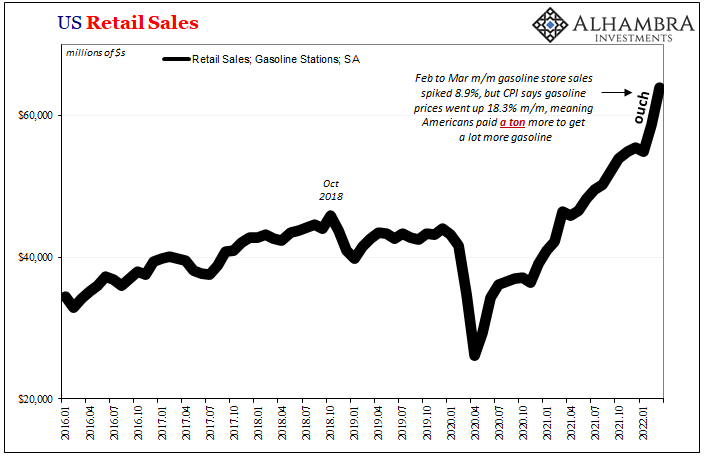

Furthermore, on the sales side there’s been far more volatility in them especially last December and again to a less extent in February then March this year. As consumer sentiment crashes for every dollar higher in oil, there’s less available purchasing volume under consumer discretion. Demand destruction, in its basic form, is when price gains in one sector literally rob from spending potential in others.

Gasoline station sales were sent skyrocketing over February and March 2022, as was the price of gasoline, leaving somewhat less for everything else.

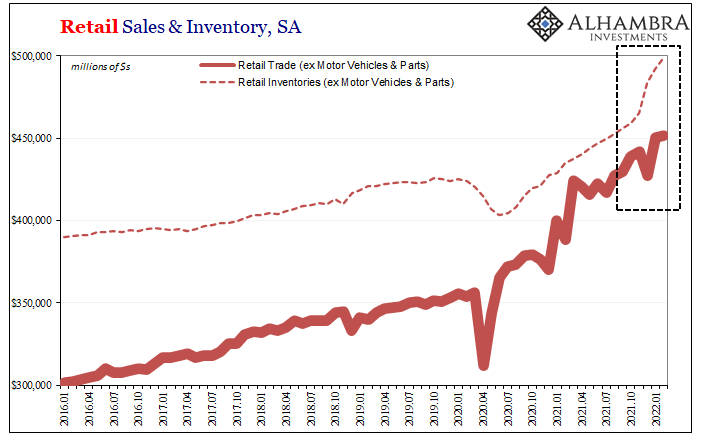

At the same time, inventory levels have turned much less volatile. Going back to October 2021, like so many markets, uncertainties surrounding the availability of excess stocks have diminished. The two ends of the supply chain have yet to get very far out of whack, but if the goods economy had to depend upon being so finely balanced by these other factors then no wonder a possible hair trigger angst at places inside of it.

Retail inventory is far from recession-level imbalances, but such is due entirely to ongoing sales. Even with them, inventory – nominal as well as deflated into real terms by the core CPI – has since outpaced those high sales; no complicated math to see where this could go.

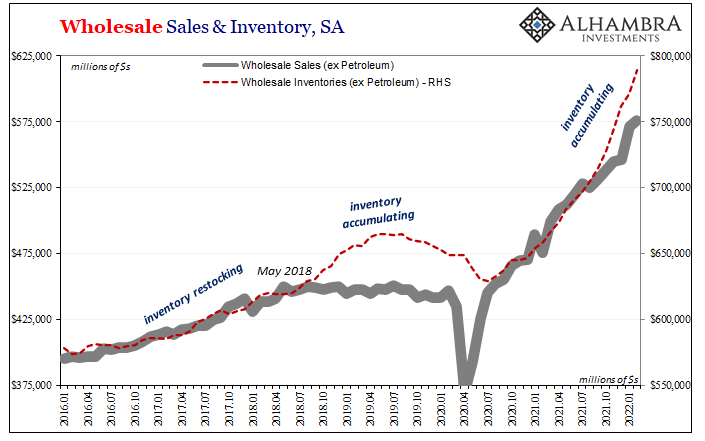

Most of it has ended up in wholesaler hands, which instead of retail lags might begin to explain the negative action, thereby potential, described by FreightWaves’ view.

If we take overall sales across the entire domestic supply chain, something called Total Business Sales, account for as much inventory as possible within it, Total Business Inventories, and then deflate both by the CPI we clearly see starting point for the supply shock.

Inventories declined in real and absolute terms last year during the helicopters since supply worldwide had become inelastic, sending prices on goods surging. Over-ordering in between, and now inventories are outpacing even continued high sales across all the supply chain tiers.

What may be becoming more visible is the other side bracket.

So, even as the inventory-to-sales ratio (either nominal or real) remains near its all-time lows, that’s not on the minds of retailers nor especially wholesalers and maybe now trucking firms. It is how likely, and how quickly, that low level might change unfavorably if consumers really do pull back, particularly in light of the one further variable not included in any of the data here.

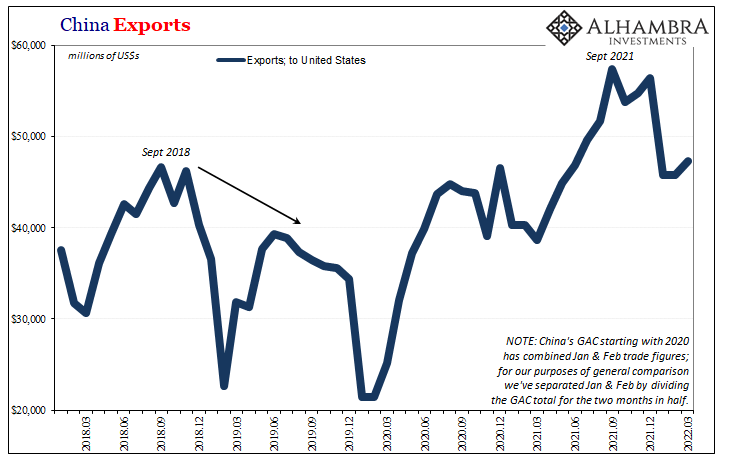

That would be overseas therefore shipped goods still in progress or in transit. A fair chunk of 2021’s supply shock was filled by stuff made overseas, aided by consumers’ preferred post-2020 mode of shopping – online.

For as much “real” inventory has already found its way into these statistics, and more to be worked into it in the coming months, how much beyond them is already being manufactured in China, Germany, or Japan? How much has been produced and still sits on a downshifted ship or waiting for railroads to pick it all up and move it into the data-stream?

If the answer is, more than we thought, then maybe you’d understand why suddenly wholesalers or retailers might now really start to call a halt with local truckers. Rethink what’s easier which means closer to the end user. In other words, the bullwhip cracks back.

Retail sales are near highs, sure, yet inventory has more than begun to start catching up. And if the two continue to head in the opposite direction, Jay Powell wouldn’t figure it all out for a long time after it becomes a substantial real economy problem. Also just like 2019.

Stay In Touch