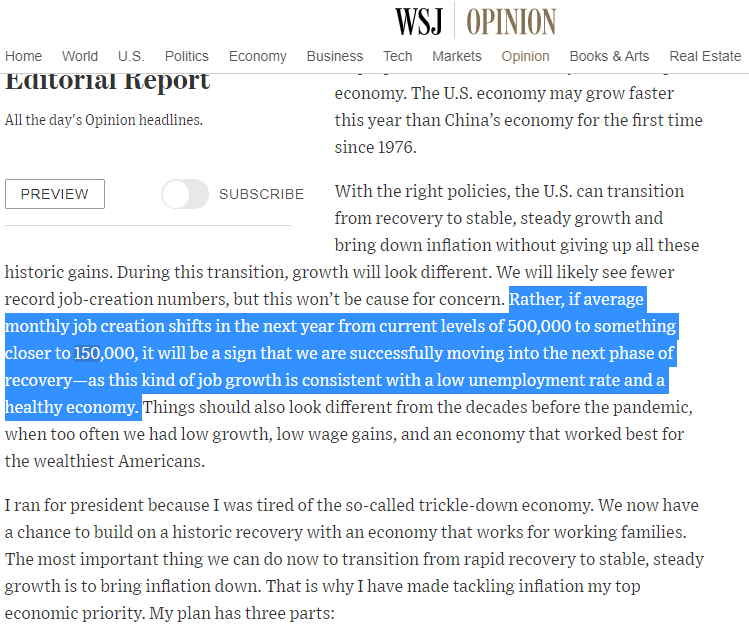

Just the other day, President Biden took to the pages of the Wall Street Journal to reassure Americans the government is doing something about the greatest economic challenge they face. Biden says this is inflation when that’s neither the actual affliction nor our greatest threat. On the contrary, recession probabilities have sharply risen as the real economy slows down given the emerging downside to last year’s supply shock.

One thing we might agree on, the President told the country to expect a slowdown primarily in the labor market from here on. In consultation with the rate-hikers at the Fed, he’s been coached into the Phillips Curve – pretending that the Federal Reserve’s policies will cool down a supposedly red-hot labor market therefore no one need worry about consumer prices over the months ahead.

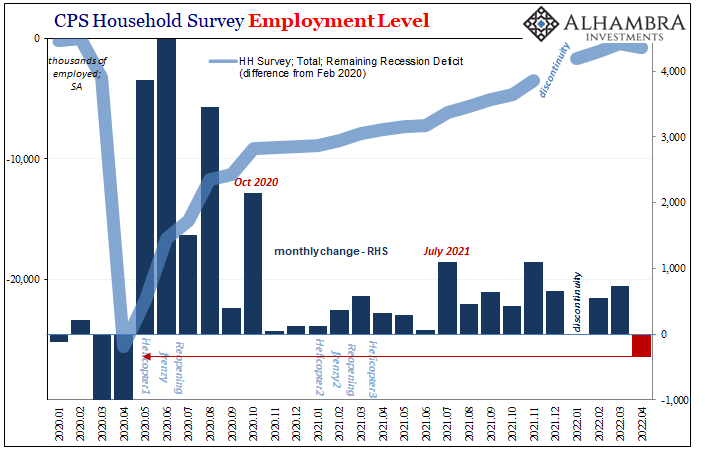

But even Biden says they will need to get used to lesser job growth though as a matter of choice. The possibility remains, however, that it isn’t his or anyone’s option and the outcome could be fewer outright jobs (as last month’s Household Survey already showed) if he’s wrong regarding this Phillips Curve nonsense.

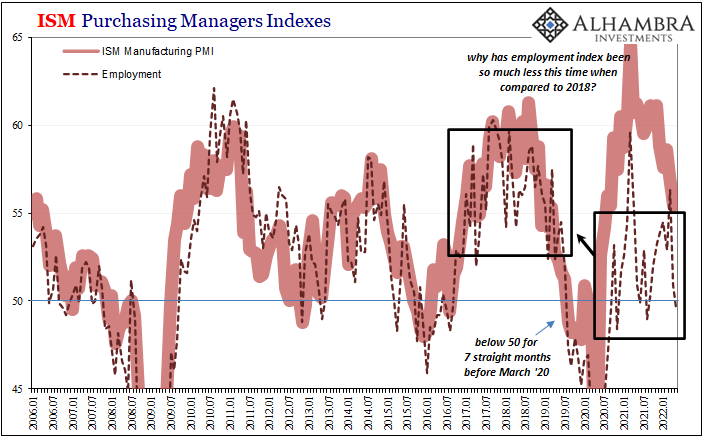

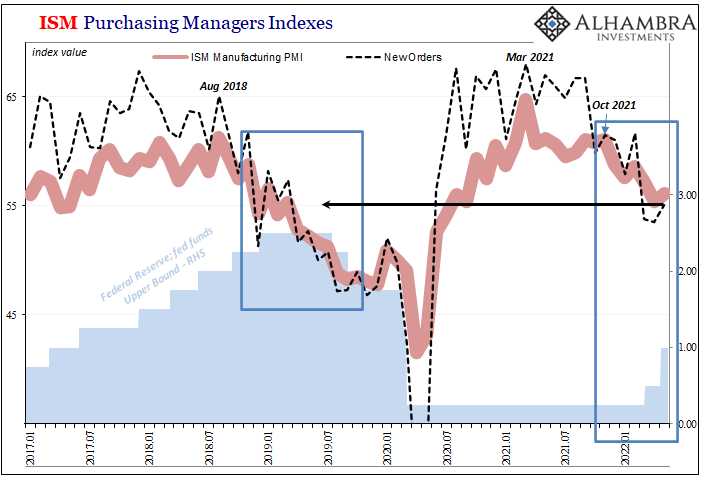

Today’s ISM data for the domestic manufacturing clutter, for example, has already reached the same conclusion as the President. While the headline number ticked modestly higher, not significant (56.1 from 55.4), the employment component dropped below 50.

After having attained a moderate peak of 56.3 back in March, the ISM’s employment component since declined sharply to 50.9 in April before now 49.6 for May. To begin with, why hasn’t this measure been so much better, particularly when compared to 2018-19?

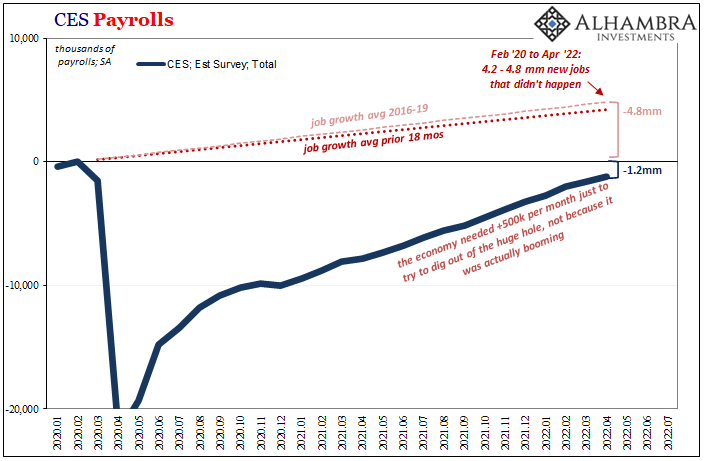

Some citing the Phillips Curve as a basis would argue this is the labor shortage plotted via ISM data. Not likely at all, instead it’s what we see in the Establishment Survey where there are today fewer jobs overall (and in manufacturing) when compared to more than two years ago back in February 2020 (the May payroll figures will be released this Friday and are likely to show, you guessed it, substantial slowdown).

The generally lower ISM Employment index corresponds only-too-well with the consistently lower jobs level (not to mention the almost 5 million payrolls that never happened).

Biden said in the WSJ that what we should expect will be nothing worse than an overheated economy and labor market downshifting to take care of inflation (the theoretical Phillips Curve trade-off, accepting less employment for less consumer price gains). The result will be happy voters appreciating the economic stability (who is he, Xi now?) predicted by exploiting these Phillips Curve tradeoffs.

To that end, the US goods economy (manufacturing) has been the lone bright spot. The ISM has already indicated there’s definitely a downside where it comes to manufacturing, not just in terms of employment but also going forward with new orders (like the headline, up an insignificant amount 53.5 to 55.1 last month).

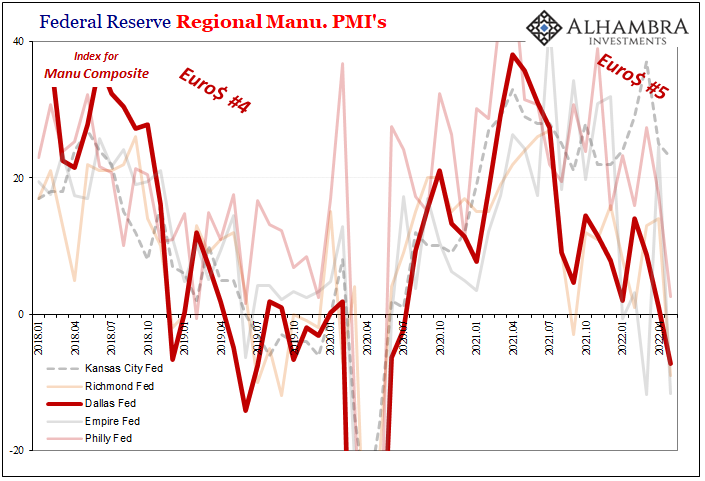

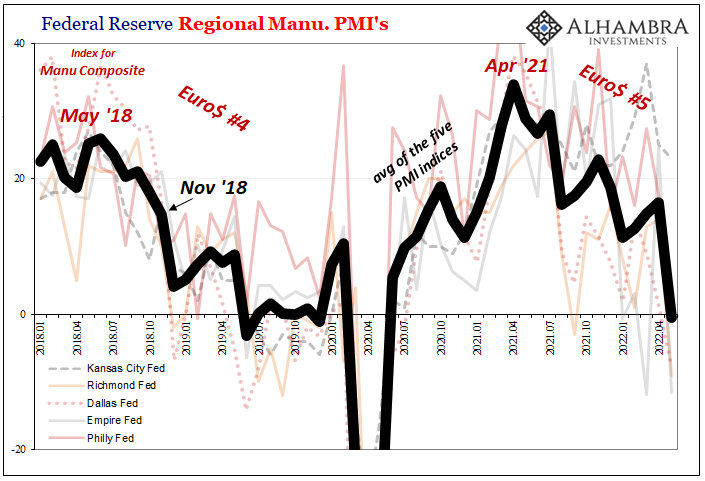

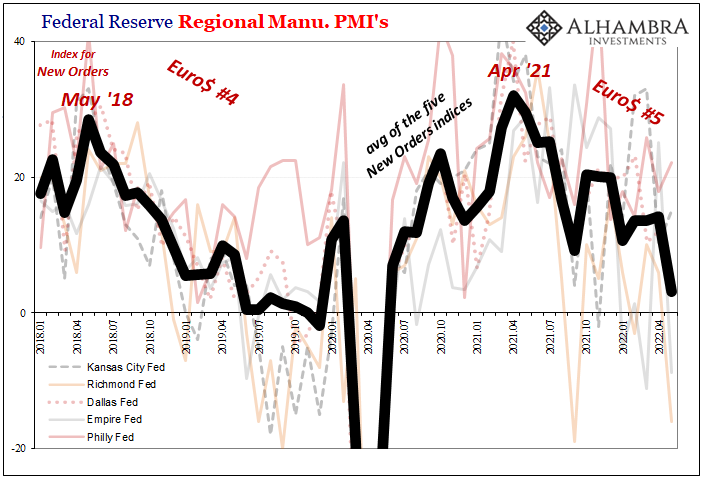

Yet, further out in front of these, the Federal Reserve’s various regional manufacturing surveys spelled more real trouble for May. Out of the five that I watch closely, four absolutely plunged; the lone exception Kansas City’s. The latest was, alarmingly, the Texas survey which really should be booming given oil prices (but we know never was).

Three out of the five have gone below zero, one (Philly) barely above, so that the average is now likewise a small minus. The various new orders indices among the quintet fared only a tiny bit better, their average down all the way to a mere +3.1.

Together, for the Fed data, anyway, it puts the economy in the same range as, well, the ISM which is somewhere like the middle part of 2019. Yeah. The same territory as when the same Jay Powell was then rushing to switch his hawkish stance predicated on the same unemployment rate and Phillips Curve view because the latter proved to be misleading and inappropriate for the real condition of a much weaker economy.

And this thing is just getting started in 2022 (just like it had been in the summer of 2019, too, only we’ve all forgotten about it because coronavirus overshadowed what might’ve been).

Even if they can’t say for sure why, both Powell and Biden have figured out there’s a slowdown afoot. They’re claiming it’s fine because the US begins that slowdown in a very good place, perhaps even exceptionally good, and then further claiming this is the result of intentional beneficial policies (rate hikes).

But is any of it true?

The data – even at this early stage – like all the markets have answered that question for you already. Not one bit; the slowdown didn’t just show up last week or last month, it’s been building for months, as much as a year and it has nothing whatsoever to do with rate hikes.

This is globally synchronized, again, after all.

Furthermore, markets point to the serious possibility the economy (globally; see: Germany, in particular) really is heading into a more serious slowdown, doing so starting from at best a questionable condition nowhere near full employment and nothing remotely close to actual recovery.

There’s a vast difference between things-are-great-so-pump-the-brakes-a-little-bit and the-plane-never-really-got-far-off-the-ground-and-now-its-engines-have-shut-down. Political theater surrounding rate hikes and now this administration-wide lean on the Phillips Curve is all about making believe of the former, hoping by little more than sheer random luck it actually happens.

You know, like in fairy tales.

Stay In Touch