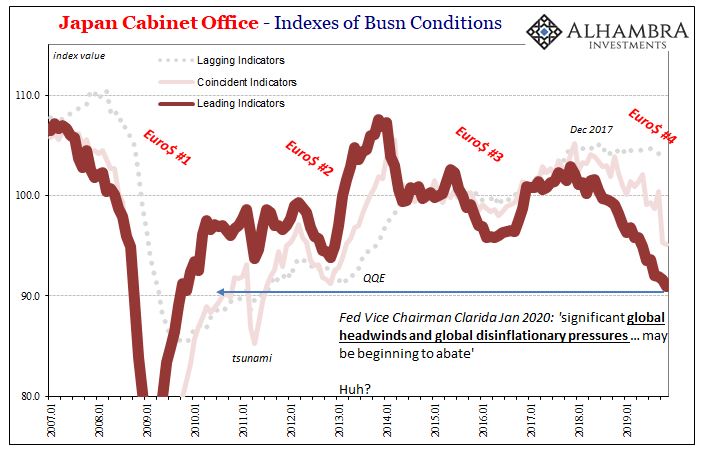

In the middle of 2018, Japan, they said, was riding so high. Gliding along on the tidal wave of globally synchronized growth, Haruhiko’s courage and more so patience had finally delivered the long-promised recovery. The Japanese economy had healed to a point that its central bank officials believed it time to wean the thing off decades of monetary “stimulus.” They even publicly speculated on just when QQE would be terminated.

At least that was the story, one which was widely accepted without question and broadcast that way. In June 2018, for example, the Washington Post was eager to tell us all about Japan’s successes. No longer would the pitiful system stand in as the primary example of economic failure, replaced as “the rare cautionary tale that’s turned into a success story.”

Always quick to hype technocratic prowess (even if half a decade or longer passes just to reach a point of plausibility), the Post’s real message was the world’s bright future. If Japan could do it, just give these Economists and central bankers your undivided attention.

This is really two stories. The first is that Japan wasn’t doing as badly as we thought 15 years ago — that’s when it really started to catch up — and the second is that it’s been doing even better than we realized the last five years. That period, not so coincidentally, is when Prime Minister Shinzo Abe started saying he’d do whatever it took to revive the country’s economic fortunes.

The only reason Japan “caught up” to the US was because the American economy has spent the last decade in a reported boom that looks suspiciously like Japan’s lost decade. Indeed, even the article’s author acknowledges how the Japanese economy “didn’t shrink at all in the 1990s but only stopped growing for a few years” as if stopped growing for a few years was some kind of achievement.

We live in a non-linear world which means that when you are in a hole already every day you don’t get out of it the hole actually gets deeper. You can’t see if from where you are at the bottom of the pit, but lost compounding forces the sides ever steeper. Prolonged lack of growth is actually far worse than the biggest temporary decline.

Japan is a forerunner, a leading indicator of sorts long run and short.

Now, whether we’re talking about robots, smartphones or housing bubbles, Japan is where the future happens first. In particular, when it comes to that last one, its boom-and-bust cycle happened a full 16 years before the rest of the world’s did.

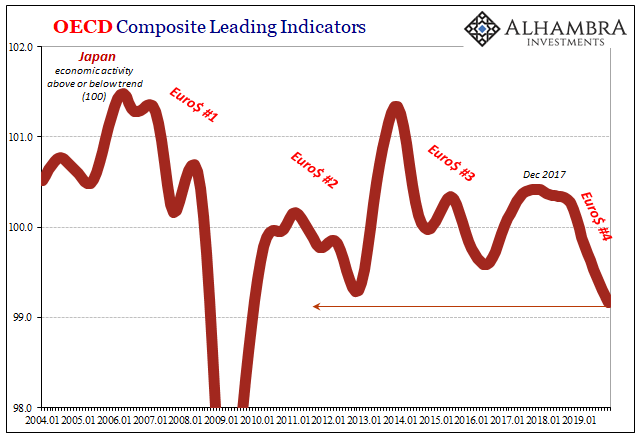

And, as usual, the technocrats not only failed to foresee those big ones they can’t seem to get a handle on the smaller versions thereafter; including what was already happening when these words were being published. The current globally synchronized downturn by then had erupted, Japan right at the front of the line leading in the opposite direction of success. Yet another devastating setback, unscheduled or not.

Though that was a year and a half ago, only now are the numbers getting serious. Forget ending QQE, the question now for Kuroda is what other letters he might pile onto the abbreviation so as to “do whatever it takes” to hopefully get back to just going nowhere.

While some point to the rise in the VAT tax rate which hit at the start of October 2019, it just doesn’t explain the level of declines, when those declines began, and more than anything their synchronized stature.

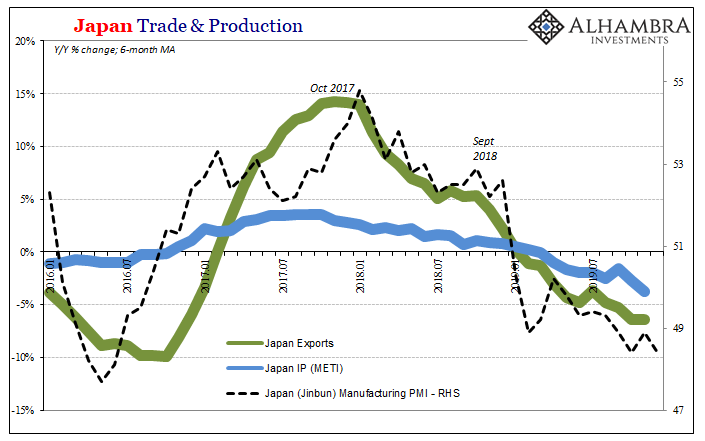

Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) confirmed yesterday that Industrial Production, maybe the best global leading indicator there is, was a little worse than first thought in November 2019. The figure was revised downward to -8.2% year-over-year, following a 7.7% drop in October. That brings the 6-month average down to -3.7%, the lowest in more than six years.

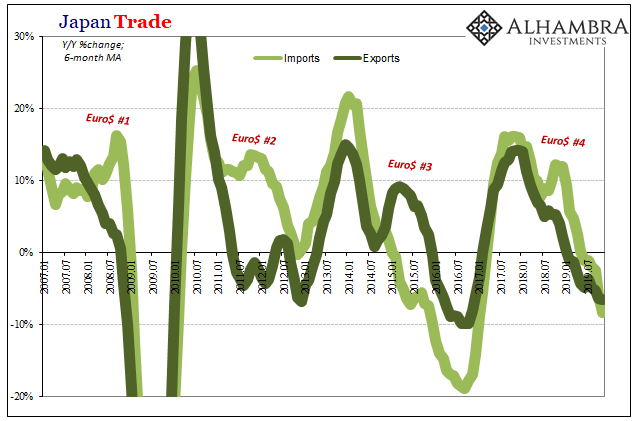

While maybe there are some tax effects to them, the fiscal change cannot explain outbound trade. As IP contracts at an accelerating rate, so does Japanese exports. These are now falling consistently at near double-digit rates and the 6-month average a sharp -6.4%. Japan’s Finance Ministry later this week is expected to report another sizable decline for the month of December.

On the other side, imports are dropping by a considerably faster rate. They tumbled by 14.7% year-over-year in October and by 15.7% in November. While taxes, sure, imports instead suggest Japanese demand is waning every bit like it did during Euro$ #3 in 2015 and 2016 when there was no such tax hike.

That is likely why despite the excuses and the positive sentiments reaching elsewhere around the world it hasn’t touched Japan’s beautiful but still-beleaguered shores. In that case, we must hope that the Washington Post was wrong about everything in that article; meaning that Jay Powell better hope Japan isn’t any longer where “the future happens first.”

For the Japanese economy as well as the whole global system, another confirmed downturn no matter how much longer it lasts is that economic pit of despair getting bigger and bigger. Neither the island nation nor any other nation can really afford to squander several more years waiting for actual rather than imagined temporary successes.

Stay In Touch