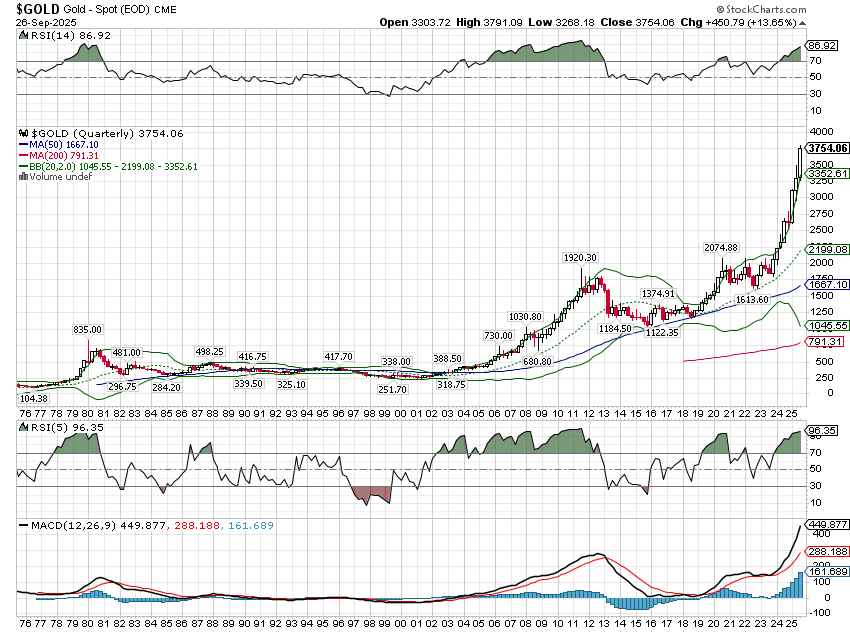

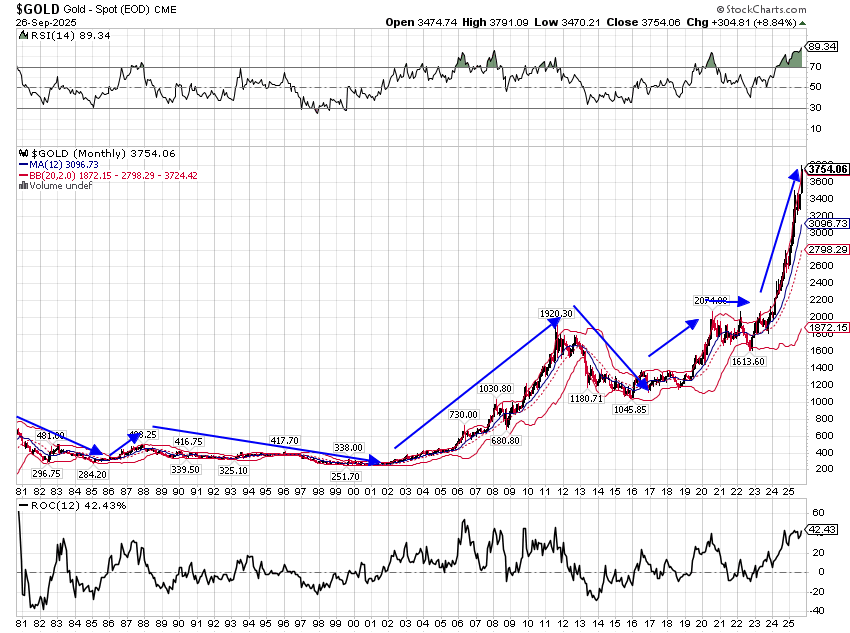

The price of gold set an all-time record last week, with futures trading over $3800 and spot prices just a bit less. The new price high was also an inflation-adjusted all-time high, breaking the previous record set in 1980 of about $3500 in today’s dollars. The most important question facing investors today is this: why has gold more than doubled in price since October of 2023? An additional question that may be relevant is this: why has the increase in the price of gold accelerated this year?

Gold hit its post GFC low in early 2016 ($1045) as the dollar rose out of the Euro crisis in the early part of the decade. It rallied some after President Trump took office in 2017 but really took off when tariffs were imposed in 2018, continued to rally as COVID hit, and finally peaked in the summer of 2020 at around $2000. It corrected until late 2022 but the rise since then has been rapid and relentless; there have been only 4 down months over the last 23.

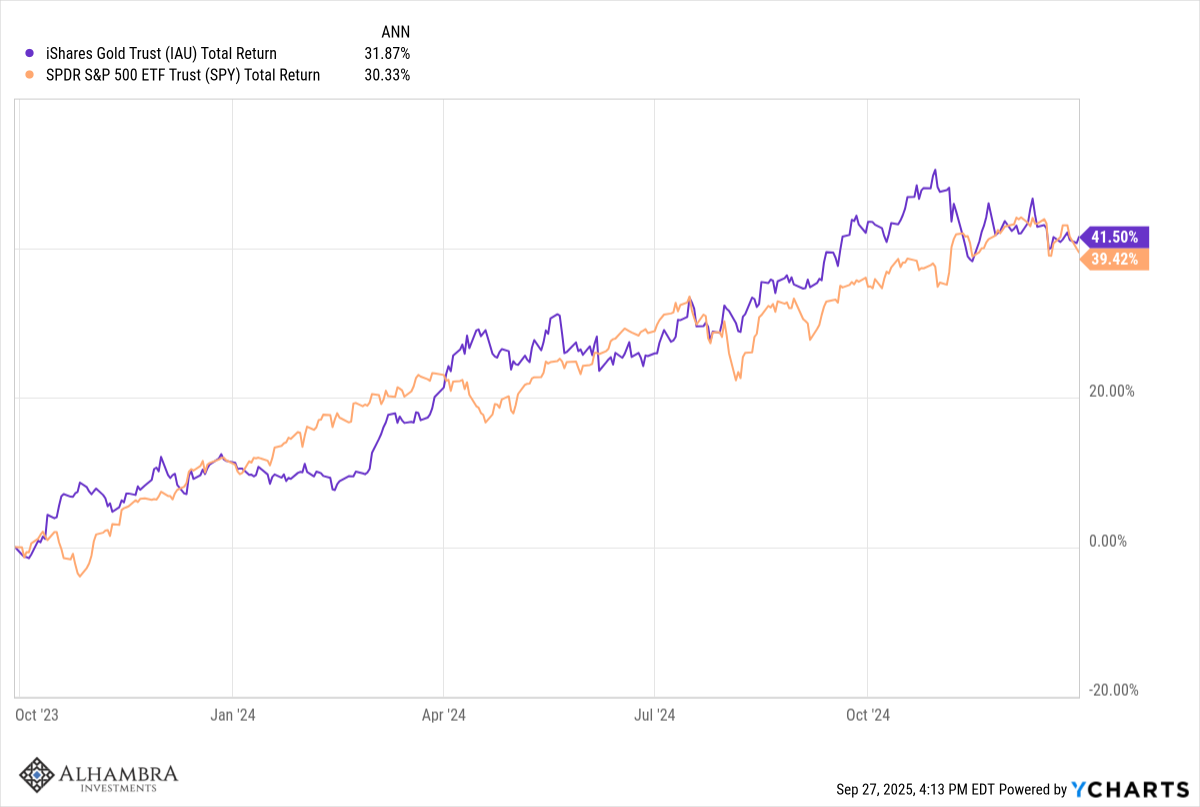

Gold rose, along with stocks, 41.5% from October of 2023 to the end of 2024.

Gold continued to rise in 2025 but at an accelerated pace that stocks couldn’t match:

It is impossible to know exactly why gold is in such high demand today because investors may have different fears and motives, reasons for buying. It is most often thought of as a good hedge against inflation and that has been true over the long term. The obvious modern example is the 1970s after the US ended the Bretton Woods monetary arrangement. There were two waves of inflation in the 1970s, one that started in late 1972 and peaked – at a year-over-year rate of over 12% – by late 1974. Inflation fell back to a still unacceptable 5% or so by late 1976 when prices accelerated again, inflation finally peaking at 14.5% in the spring of 1980. With the dollar falling nearly 30% from the end of Bretton Woods to the inflation peak in 1980, gold did exactly what we would expect, protected investors from a devaluing currency – and inflation – just as it has throughout history.

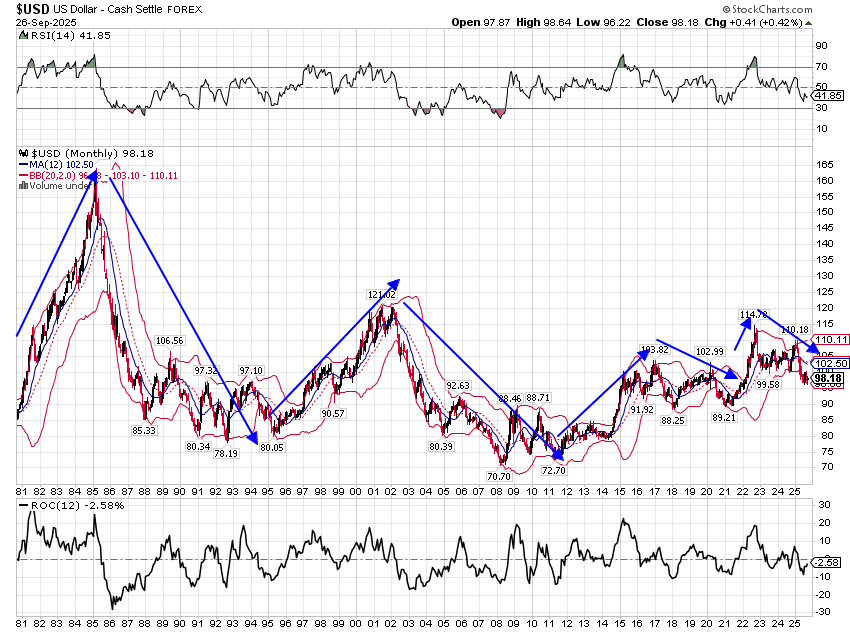

Gold and the dollar maintained this inverse relationship through the next 4 decades and it continues today, the buck down 15% and gold up 130% since the dollar peaked in late 2022.

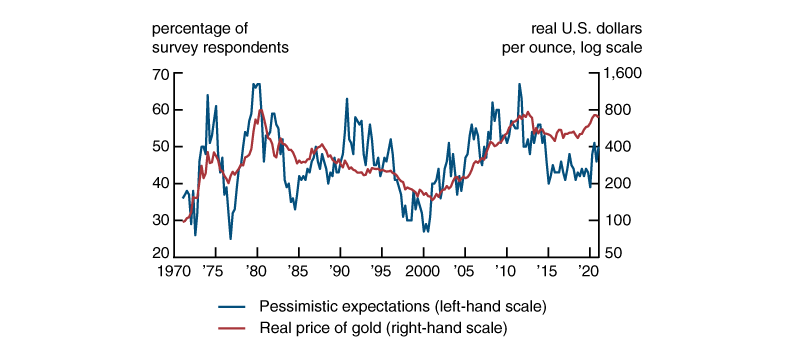

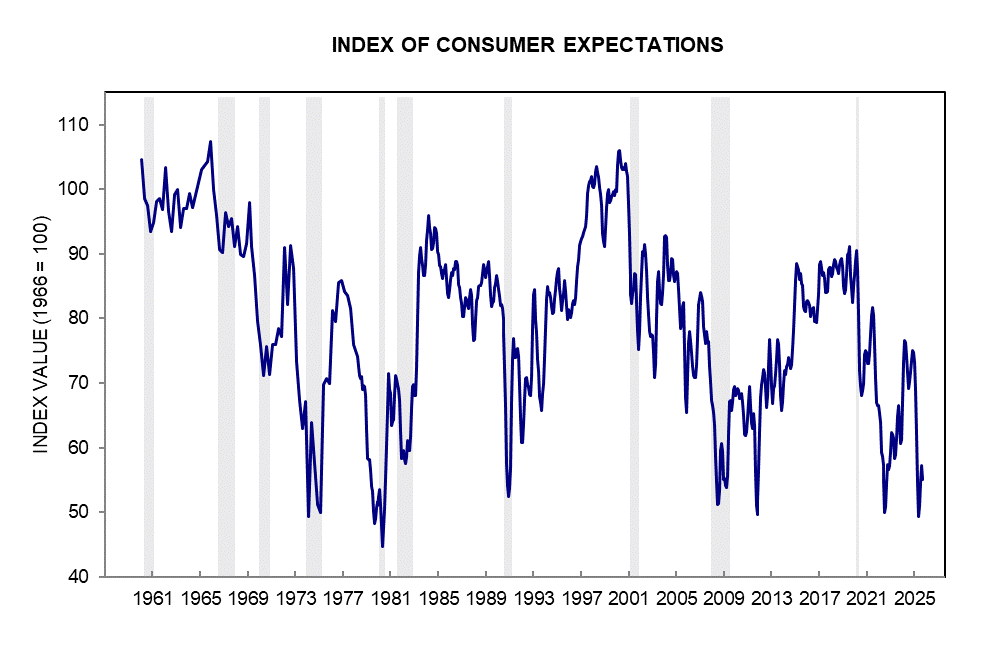

What drives the price of gold? From the 1970s to the turn of the new century, gold tracked inflation expectations but that hasn’t held true in the 21st century. After that, real interest rates were predictive of gold prices; gold prices rose when real interest rates fell and fell when rates rose. That relationship started to sour in late 2022 and gold’s most recent rise has coincided with higher real interest rates. The one thing gold has responded to consistently over that entire period is expectations for the future as recorded in the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment polls. When people are pessimistic about the future, they buy gold and when they become more optimistic, they sell it.

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

In a sense, all of the things that gold has seemingly responded to over the last 50 years can be equated with this one metric – confidence about the future. In the 1970s, the huge change in the monetary system and the inflation it generated created a pervasive pessimism that culminated with Jimmy Carter’s so-called Malaise Speech in the summer of 1979:

I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy.

I do not mean our political and civil liberties. They will endure. And I do not refer to the outward strength of America, a nation that is at peace tonight everywhere in the world, with unmatched economic power and military might.

The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.

The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America.

(Emphasis added)

Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” first term saw gold fall and the dollar rally as confidence returned. Iran/Contra, the rise of Japan, the S&L crisis, and the first Gulf War in the second half of the decade reversed that feeling. The second half of the 90s brought the dot com boom, which was all about rising confidence in the future; gold and other commodities were afterthoughts. The dot com bust in the early ’00s, along with corporate scandals, 9/11, and Gulf War II spurred another round of pessimism; gold soared, the dollar fell. The Great Financial Crisis pushed gold to its 2011 high, while the recovery sent gold lower and the dollar back up again. Tariffs and COVID in Trump’s first term brought back the fear and while gold steadied from 2020 to 2024, the lack of confidence in the future persisted.

The second election of Donald Trump certainly fits in with the theme of a lack of confidence in the future, extremely so in the case of those who voted for him. His tariffs and immigration policies are certainly creating new fears about the future of the US and global economy. But it is an odd time right now with stocks and gold both sitting at all-time highs. Artificial intelligence is driving a massive increase in corporate investment, a huge bet on a brighter future, which is driving stock prices. At the same time, the dollar is down 15% from its high and central banks are furiously adding to their gold reserves as their confidence in the US and its currency wanes.

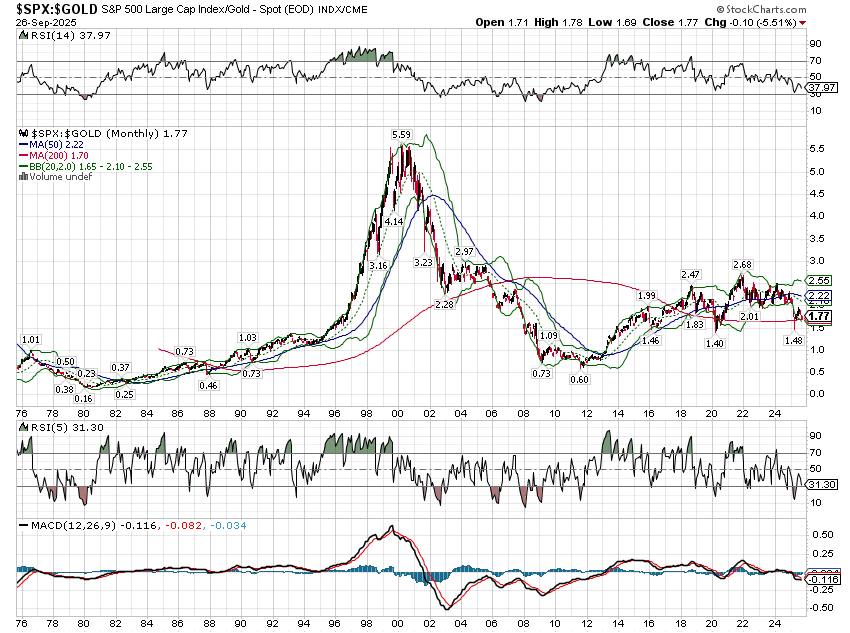

The rise in gold, however, has been more extreme than the fall in the dollar would have predicted and its relationship with other assets is reaching extremes.

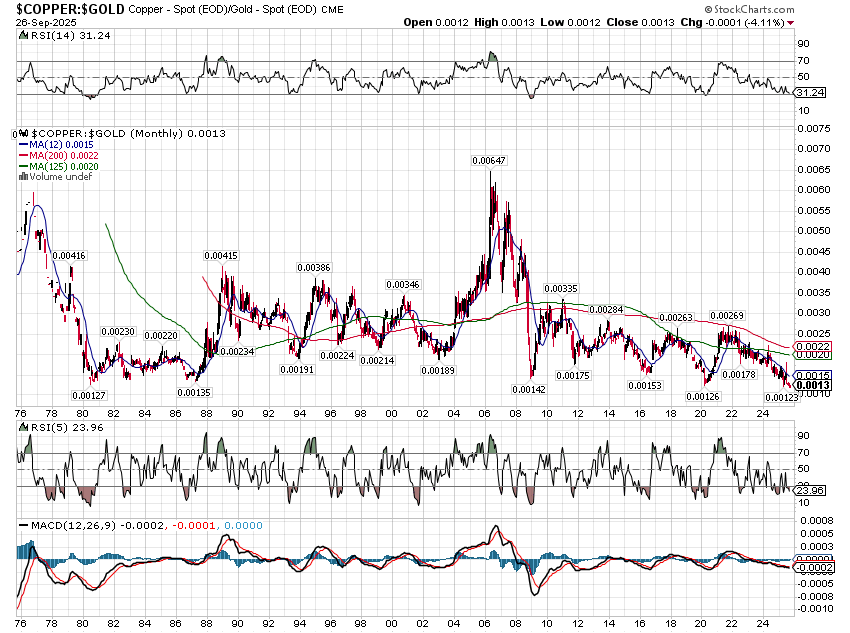

The ratio of the price of copper to gold is at a low not seen since those dark days of 1980:

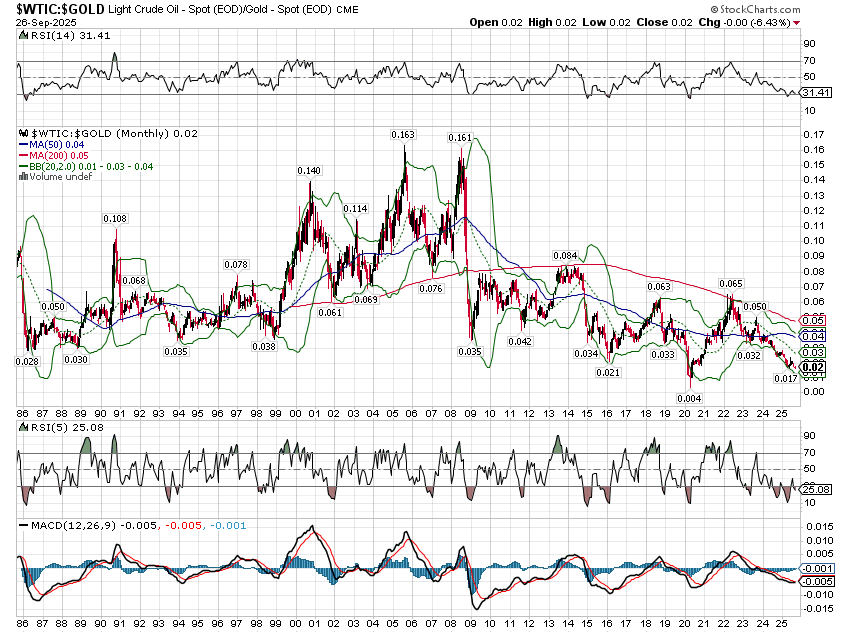

The only time in the last 40 years that crude oil was cheaper relative to gold was when oil prices turned negative during COVID:

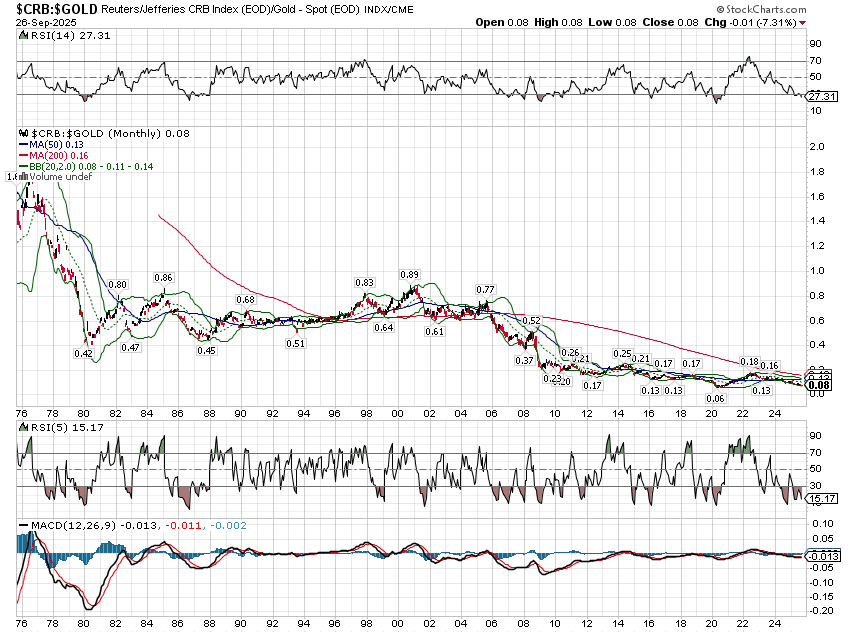

Other commodities are also cheap relative to gold: Platinum and Palladium are just off multi-decade lows. While there are a few exceptions, most agriculture prices – corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton – are at all-time lows relative to gold. Lumber was only lower in the aftermath of the 2008 housing bust. The CRB commodity index – a more diversified index than the GSCI – is near an all-time low, the COVID lows the only exception since at least the 1970s.

With the Shiller P/E recently passing 40 again – not seen since the dot com boom – there has been some talk about how expensive stocks are, but if you compare the S&P 500 to gold, they aren’t anywhere near the heights of the dot com peak. I think that just shows how ridiculous that era was and anyone making that comparison today likely wasn’t around then. This isn’t even close to the madness we saw back then. But that doesn’t mean today’s markets are a bargain.

Market extremes are points of opportunity but they aren’t easy to navigate – extremes can get more extreme. There are also numerous ways the extreme can be corrected. Gold could continue to rise while other commodities rise faster. Gold could fall faster than, say, platinum. Gold could fall while crude oil rises. Knowing there’s an extreme does not mean there’s an easy way to profit from its reversal.

One clue might be that some of these commodities are already starting to rise to meet gold. Platinum and Palladium are up 77.7% and 44.2% year-to-date. What hasn’t moved this year is crude oil, down a little over 9%, but it is interesting that production increases from OPEC+ don’t seem to be affecting the price much. Will crude oil be the next commodity to start playing catch up to gold?

The outcome, how this extreme move in gold is resolved, can be simplified even further. In the end, markets reflect the uncertainty of the future economy, with stocks representing the optimism of AI and gold representing the pessimism about Trump’s policies. On the former, I am more than a little skeptical that the current spending on AI infrastructure will produce an acceptable return but I could certainly be wrong about that.

As for Trump’s policies, I would point you to Stephen Miran’s speech last week in which he laid out his rationale for why the economy needs much easier monetary policy right now. His speech focused on R*, the so-called neutral rate that represents the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate that would prevail when the economy is operating at its maximum sustainable level (full employment) and inflation is stable. In short, he believes that R* – which can’t be observed or calculated – is roughly 0% or about 1.75% below current rates because of reduced immigration and tariffs. And why would those things reduce R*? Because they reduce the economy’s growth potential. I suspect he revealed more than he intended with that speech but if he’s right, then the move in gold makes perfect sense and so does the chart below.

University of Michigan

Note: Alhambra and/or its clients and employees own gold (IAU, GLD, PHYS), platinum (PPLT), palladium (PALL) and general commodity indexes (GSG, COMT, PDBC). This is not an investment recommendation and our positions could change at any time without notice.

Stay In Touch