What’s going on in China? It’s a question that is on everyone’s mind. While most attention is focused on the unfolding human tragedy of the COVID-19 pandemic, the potential for it to be compounded by any economic fallout makes for even more urgency. The sad truth is that China was in rough shape heading into the coronavirus.

How rough, though?

It can make quite the difference. Sticking with the virology theme, a relatively healthy body is better equipped and therefore stands a better chance of handling an infection without serious and long-lasting complications. An already-weakened system is more prone to passing whatever critical threshold.

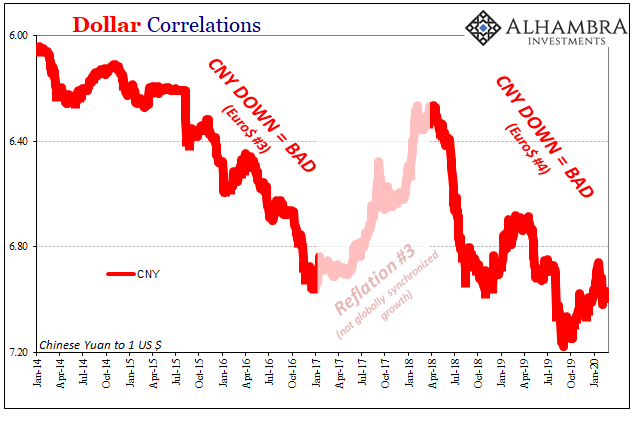

There are any number of ways to look at the situation in order to help make our assessment. Economic data and non-economy related factors. A big one is, of course, CNY; the country’s primeval connection to the global economy through its lifeblood eurodollar system.

The first thing that stands out about China’s currency is how very different it has behaved this time (Euro$ #4) as compared to the last time (Euro$ #3). The end result is the same regardless, “devaluation”, which only goes to show that it isn’t the central bankers and monetary authorities who are actually in charge.

You can plainly see the difference; during 2014-16, the exchange rate took more of a stepped approach in its plummet. Apart from that one day in August 2015 (stimulus!), it was a back and forth battle of ticking clocks. The clear signs of heavy and often repeated interventions.

Over the last few years, by contrast, much less so. When the currency drops it just goes almost straight down. Any interventions must have been at least less frequent if not also far less intensive each time. It’s as if Chinese authorities had realized the futility of what they had done the first time around, and how the significant costs to the interruptions were not worth the expense since the currency was going to drop no matter what.

The only thing that actually stopped the currency’s bleeding was Reflation #3 (with an unhealthy dose of Hong Kong). The eurodollar system itself spared China – for a little while.

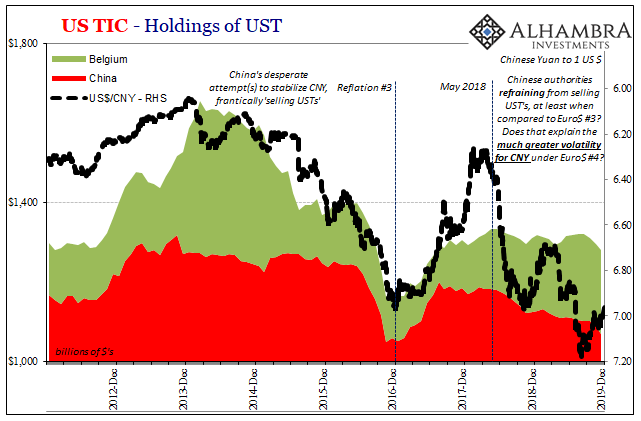

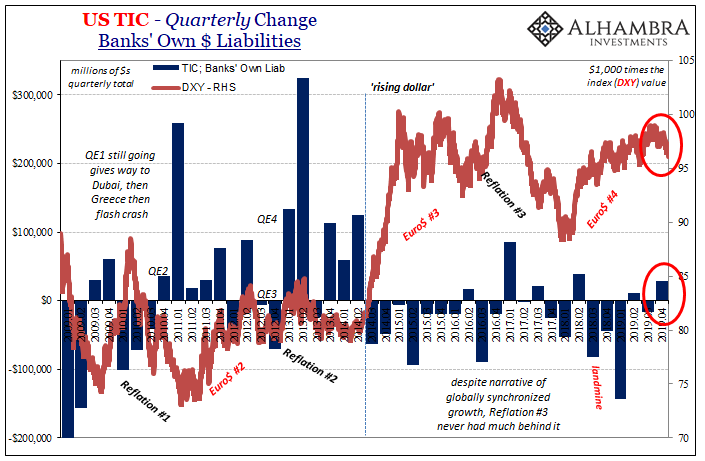

The Treasury Department’s TIC data gives us some welcome background information and confirmation for what we see in CNY’s price behavior.

Sure enough, according to the Treasury Department’s custody data, Chinese authorities did respond if not over-respond to Euro$ #3. They frantically sold or at least mobilized (sold forward) UST’s and reserves leading to the very different pattern in that prior decline.

Compare that to Euro$ #4 where the level of UST’s (including Belgium) simply stopped rising. Mainland holdings have dropped particularly since May 2018, but some of that has been due to posting collateral at Euroclear (located in Belgium) for whatever smaller, infrequent if still clandestine currency operations. A far more “hands off” approach this time around.

Thus, CNY’s tendency to fall uninterrupted once it got going (the exception being 2019’s “ticking clocks” which seems far less effective than those employed during #3).

What, then, might we make of the prospect that something has changed with regard to mobilizing UST’s? How does it impact China, the eurodollar system, and the rest of the world if the PBOC and SAFE might be together regressing back into a 2014-16 paradigm?

To begin with, understand the purpose behind intervention. It’s a temporary situation, or supposed to be, where you do something believing that in a few months’ time the underlying problem will be resolved. The more confident you are that “it” is nearing its conclusion, the more likely you are to get more heavily involved thinking you are right next to resolution.

This likely accounts for 2014-16; the PBOC mistaking Euro$ #3 for “transitory” factors that ultimately proved to be a multi-year disinflationary and economically destructive process (the headwinds). Chinese authorities intervened several times each time thinking it was the last time.

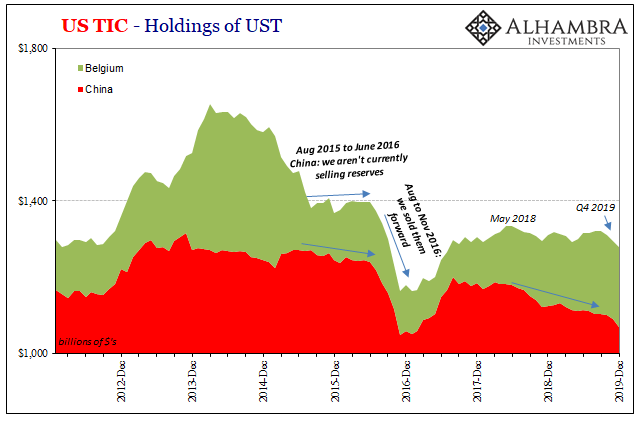

That’s the possibility the TIC data gives us. Going back to October last year, the decline in Chinese UST holdings (including Belgium) has accelerated – especially during December 2019. The Treasury Department says that the mainland’s balance declined by $32.5 billion during Q4; -$40.6 billion when including what’s in Belgian custody.

Now there are a couple of ways to consider and interpret this. The first is trade wars and trade deals. The US doesn’t want a weaker yuan, the President expressing his gross distaste for the “stronger” dollar many times the past few years.

Unable to make the connection between the dollar and why CNY has been dropping, it is apparently American policy to blame CNY’s behavior on Chinese authorities who are actually working for the same goal – to keep the currency at least stable if not rising (as in 2017). Might they have been working that much harder in order to reach a trade deal?

Keeping CNY around 7 could be a way of placating the wrongheaded “currency manipulator” critics, which would be an increasingly expensive (and long run unhelpful) bargaining chip. A bunch more UST’s would have to have been sold, as the data suggests, along with a bunch more to keep it this way.

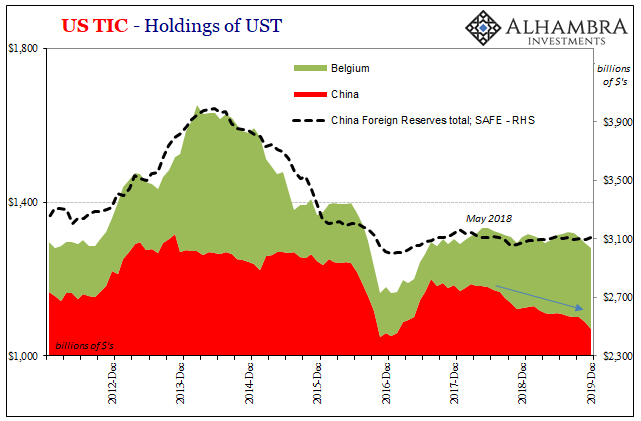

There is also some disagreement among viewpoints. TIC says UST’s are disappearing again at a rapid rate while China’s SAFE suggests a relatively more stable situation. It reports instead a steady, slightly rising level of total “reserves” (which includes all forms and currency denominations).

This interpretation, though, is further complicated because some of what SAFE includes is actually due to the fall in CNY’s exchange value (SAFE reports reserves at market prices). That makes the market value of all reserve holdings, including those left in dollar reserves, more valuable.

There’s no separating price from volume in this method.

With CNY dropping back toward and perhaps through 7 again, we should also consider other possibilities. Though the eurodollar problems were overall less intrusive during Q4, as we’ll see in a minute, that didn’t actually mean what it was taken to mean.

In other words, the modest improvement over the last few months of 2019 wasn’t really improvement so much as slightly less negative and less direct pressures (second derivative). These didn’t disappear, an end to a global recession scare, maybe even starting to swirl around the global monetary system again as 2019 drew toward a close.

The banking data included within TIC shows that for Q4 there was an overall net increase in aggregate cross-border liabilities, the highest, actually, since the second quarter of 2018. That fits with what we observed in the broad behavior of the dollar (not just against CNY) falling gently throughout the last few months of last year.

However, both make it sound like more than it really was; neither of those indicated categorical changes in condition. That’s just how everyone talked about and interpreted them, especially the dollar (the upward trend was broken forever!) And if the Chinese were actually involved “selling UST’s” at a much more intense rate, then that would explain (some of) the artificiality and therefore (some of) 2020’s sharp snapback higher.

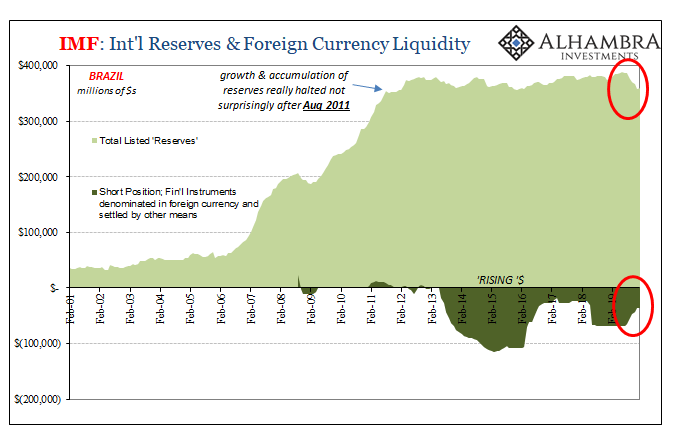

Did China pull a Brazil?

But because Jay Powell (and Richard Clarida) has said everything’s back to normal again, Banco has actually been paying those [swaps] off…with reserves. Going back to last August, Brazil reports (to the IMF) that its outstanding balance of these swaps (reported as “financial instruments denominated in foreign currency and settled by other means; e.g., in domestic currency”; see below) has declined by a little more than $33 billion. At the same time, total reported forex reserves have fallen by $27 billion.

I have to wonder (and to be perfectly clear, we’ll never know for sure; China unlike Brazil reports little to nothing of these kinds of its activities) if Chinese authorities were thinking the same thing as Brazil’s; Euro$ #4 (which they’ve yet to properly identify apart from non-specific “disinflationary pressures”) had reached its conclusion. Therefore, take advantage of what should’ve been Reflation #4 by paying down those past indiscretions under the cover of the anticipated positive dollar reflow.

Which should never have been expected in the first place. As I also wrote last week:

What that says is two things: first, authorities really did believe that the dollar was done rising, or at least done rising against the real, and that the eurodollar system would start pumping “dollars” back into Brazil again; second, it didn’t happen.

When it comes to all things dollar, the last thing you ever want to do is listen to the people who everyone is led to believe is officially in “charge” of the currency. You would’ve thought the Chinese would’ve figured that much out from Euro$ #3 (if not Euro$ #2).

It’s a way of making further weakness from a misreading of what isn’t actually strength. The consequences are whatever fallout from the sharp reversal which seems to have materialized in 2020.

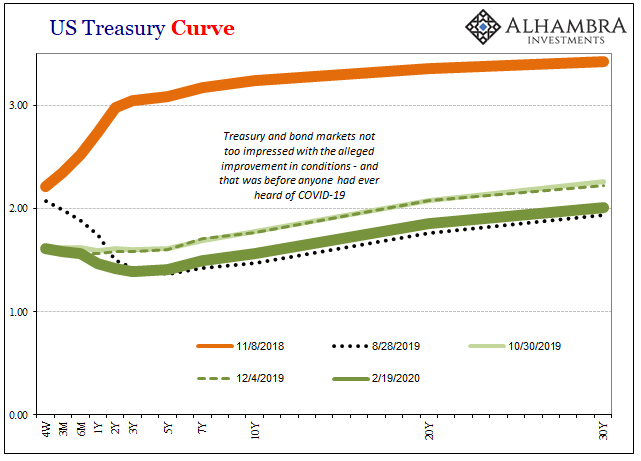

As you can see in all the curves, the last quarter of 2019 wasn’t actually better and thus it would’ve been an inopportune time to start believing that it was. Though we don’t know why there are now so much fewer UST’s in Chinese hands, unless Euro$ #4 actually did or does draw to a close China is in much worse shape to handle itself.

The weak patient was never cured but was taken prematurely off support and is now exposed to the (re)spreading (dollar) disease.

Stay In Touch