Being a member of the institutional “elite” means never having to say you’re sorry; or even admit that you have no idea what you are doing. For Christine Lagarde, Mario Draghi’s retirement from the European Central Bank could not have come at a more opportune moment. Fresh off the Argentina debacle, she failed herself upward to an even better gig.

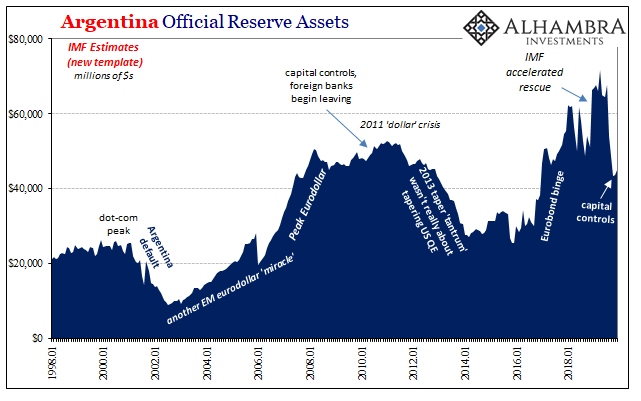

Lagarde had staked a lot on the organization’s largest ever rescue plan. It was a show of force meant to shore up confidence. The IMF still mattered to a system that still worked the way everyone in it still thought. Throw fifty maybe sixty billion at this small country in South America and wake her up for the parade.

In the wake of the peso’s devastating plummet (I won’t show you the chart for it here because what’s the point now with re-imposed draconian capital controls?) the new Argentine government is facing a stark reality. The dollar door is about to be slammed shut on them all over again.

Lagarde’s old comrades today admitted, get this, “IMF staff now assesses Argentina’s debt to be unsustainable.” What that means is obvious, steep bond haircuts and widespread debt restructuring. The very default mechanisms the 2018 rescue was supposed to rescue the country from.

How did it fail?

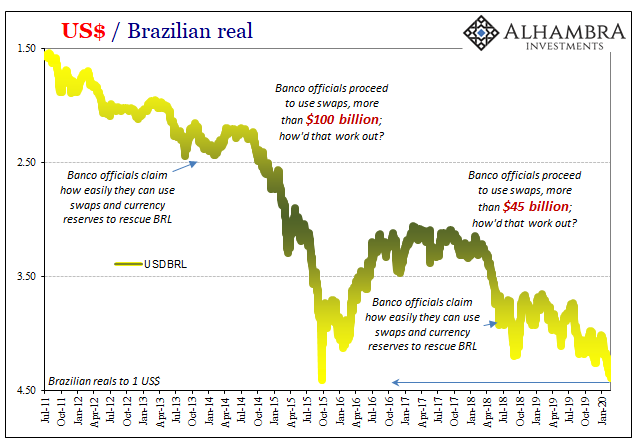

This is a question everyone asks (except those in charge of hiring at the ECB) but almost no one follows to its logical end. The purpose of any bailout like Argentina’s is to buy the country time, the same thing as when China’s PBOC or Brazil’s Banco intervenes in their own dollar backyards. They all seek some space in order to maintain order long enough for a resolution.

In each of those cases, the two on their own, the other with the IMF’s assistance, they buy time so that the problem can be fixed. When it comes to now accepting the failure of Argentina’s bailout, what everyone will conclude is that Argentina must not have been fixable. The place is, most often, a basket case.

And while that is true and certainly relevant, it does not preclude the other possibility one bit. That Argentina’s dollar problem wasn’t actually Argentina’s alone. If that was the case, then buying time would have meant a lot more than keeping the country afloat until it got its house in order.

A systemic dollar problem instead means that such a thing isn’t possible (the headwinds keep blowing from this global disinflationary pressure). It also means that buying time can only possibly succeed if at the end of that time the dollar system’s situation has been rectified. Which today no one believes is a problem.

In other words, the IMF sought to fix Argentina never considering that it would first have to fix the dollar – which it, nor anyone else, currently can.

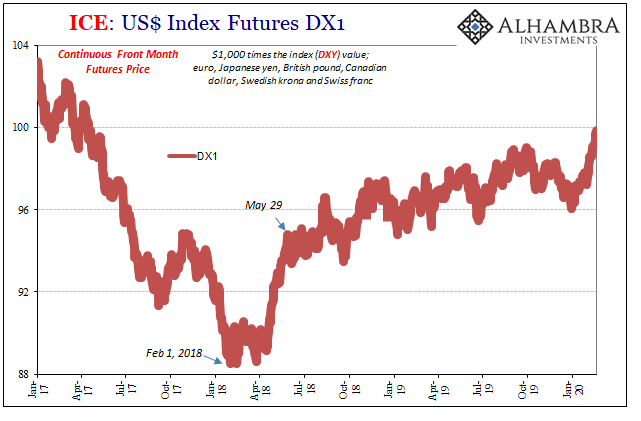

And why isn’t this ever considered? The legend of QE and its money printing puppet show. There can’t possibly be a global dollar shortage because the Federal Reserve has printed trillions in bank reserves. It doesn’t matter how much evidence keeps piling up all saying the same thing, shortage, officialdom begins and ends its frame of understanding with QE as an effective remedy.

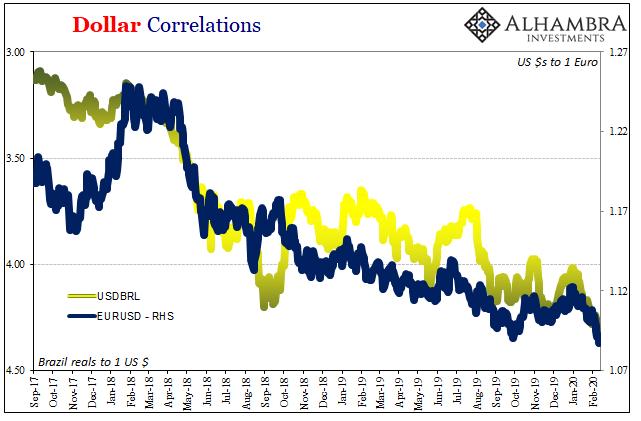

Which places Lagarde right where she belongs, in charge of another central bank right at this moment doing it – again. And what’s the euro up to lately? Very rising dollar there, too.

If nothing else, you’d think there’d be some pause somewhere out there from how many times QE has to be repeated. It’s the most powerful monetary stuff ever invented, so powerful you have to keep doing it. Something’s not right, and it’s not as if we couldn’t have seen this coming. After all, Japan and its 23 QE’s (or is it 24?)

DXY very nearly touched triple digits today for the first time since April 2017. A multi-year high wasn’t supposed to be possible because, we’ve been constantly told, everything started to go right many months ago. Not the least of which was because of one QE in Europe and another not-QE in the US.

Tell that Argentina. And Brazil. The latter’s central bank intervened in its currency markets last week, and already its currency, the real, has dived well past where it was before the intervention like Banco wasn’t even there.

Banco, as Christine Lagarde, just wants to buy more time. But time for what? These global shortages, eurodollar squeezes, have proven time and again that they can last for years – outlasting rescues and bailouts with ease. This latest one’s already past its second birthday and, by every measure, still going strong.

Euro$ #4 will eventually come to its own end, on its own terms regardless of the Fed or ECB, but these eurodollar cycles from squeeze to reflation and back to squeeze again will not until someone in one of these places finally figures out the issue isn’t Argentina, or Brazil and China, but dollar.

It’s been twelve and a half years already, so I’m not holding my breath. And if I was a central banker in one of these places, I wouldn’t be trying to buy time, either. Then again, as we’ve seen with Christine Lagarde, which way of thinking actually gets rewarded at least in these places of so-called authority?

Stay In Touch