What changed? For over a month, the Treasury market had the Fed and its rate hiking figured out. Rising recession risks had been confirmed by almost every piece of incoming data, including, importantly, labor data. It is the jobs market where much of the official “inflation” jawboning is centered, all that Phillips Curve stuff.

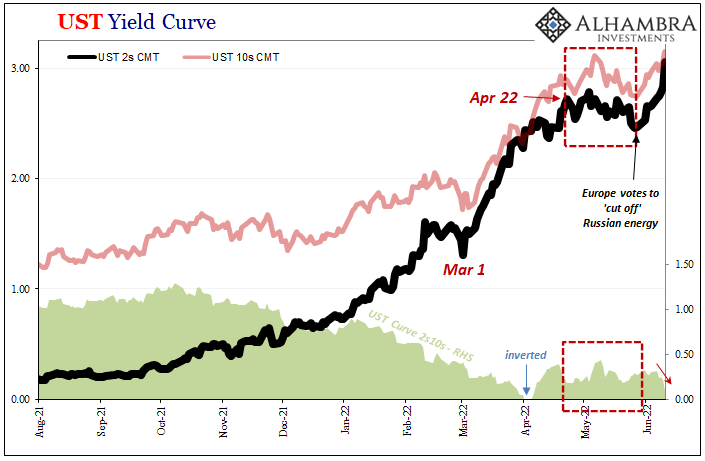

So, whatever might seriously undermine Phillips would put the end to the rate hikes in sight. Short-term Treasuries therefore ignored everything that happened between late April and the end of May, the key 2-year note sideways to lower over those six weeks projecting forward that very end to Powell’s plan.

On May 30, however, the Europeans insinuated themselves via the Russian conflict. While America was solemnly observing the Memorial Day holiday, the 27 countries of the EU finally agreed to terms on terminating purchases of whatever crude Russia manages to deliver via seaborn methods.

Covering an approximate two-thirds of what they import from the pariah, even factoring inevitable cheating that’s a huge chunk of oil about to go missing from the rest of the Continental economy.

Boom for oil prices with yet more supply left in doubt. Trouble for Jay Powell, though.

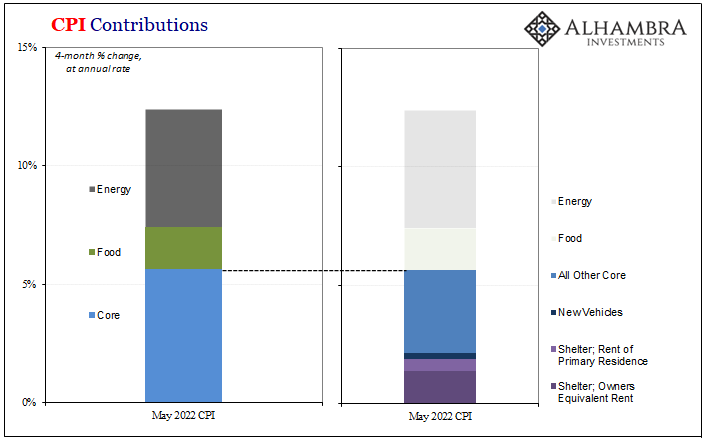

In econometric terms, whatever the CPI might have theoretically “benefited” from softer labor (as President Phillips himself warned) would be undone by the European Price Hike™ being added to the Putin Price Hike™.

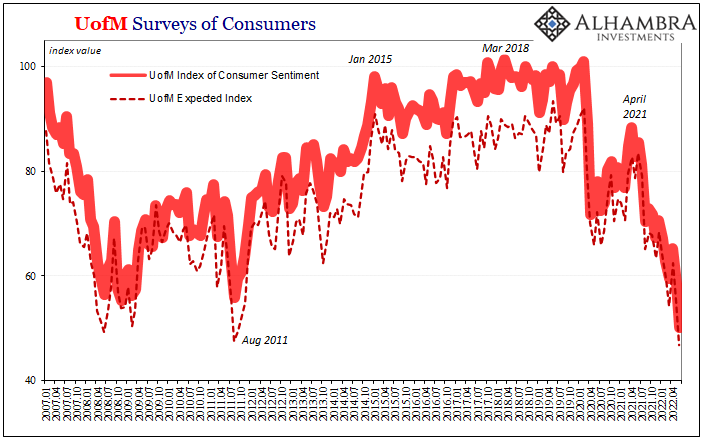

It’s pretty obvious at this point, Fed’s rate hikes are really about politics anyway, with various policymakers making it amply clear that they’re rate hike target is, essentially, the CPI regardless of what happens with the rest of the economy. For non-economic reasons, FOMC priorities therefore being set in the oil market.

After today’s CPI blown higher by, yep, almost exclusively gasoline prices, the point punctuated by another round of headlines decrying this latest 40-plus year high for “inflation.”

Emboldened by the potential from Europe, confirmed by consumer prices in May, the prior balance of perceived policy fears has shifted back toward CPIs from recession. Regardless of whether the FOMC really appreciates the growing possibility of the latter, they’ve left themselves no alternative but to further prioritize the former.

Higher future oil, higher future gasoline, the stickier the CPI will be (offsetting recessionary forces which will be lowering other goods prices over the months ahead), the stickier rate hikes end up. The market via the 2-year UST rate has since redone the probable rate hike path reflecting this new crude calculus.

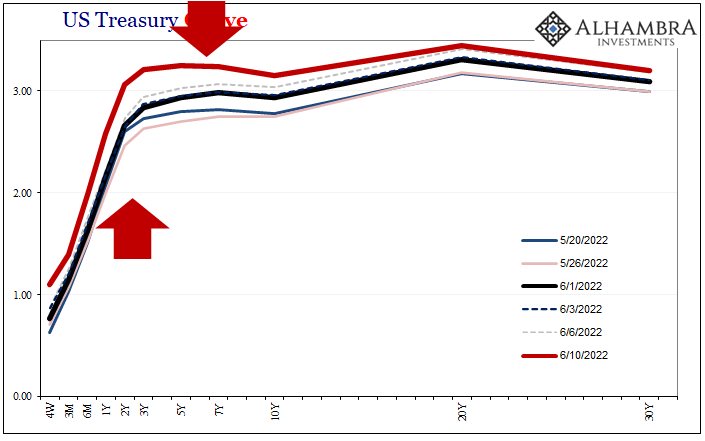

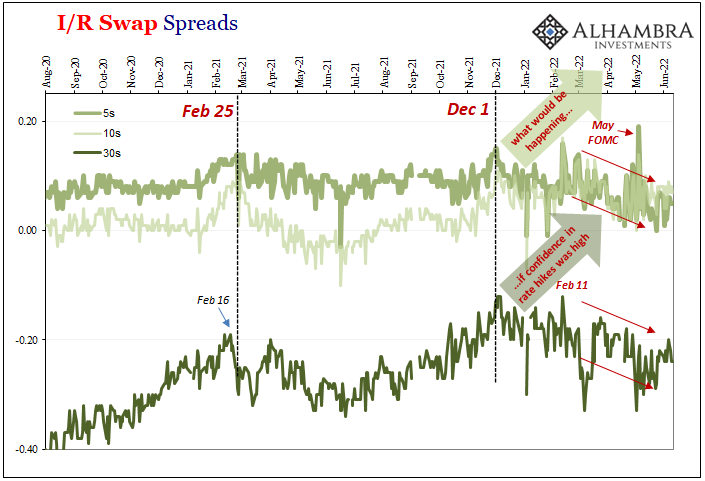

That’s where it ends, however. As my friend Mr. Tateo reminds me, for all the inflation hype and certainty Greenspan’s series of one-year forwards are taking it on the chin again today.

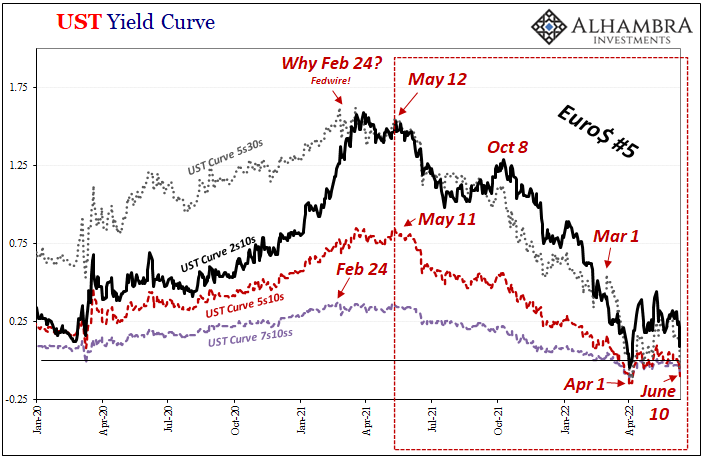

In other words, the yield curve has flattened and importantly re-inverted in significant fashion for all this Europe-based trouble. Prospects for maybe more and prolonged rate hikes (again, regardless of recession risks; see: Europe in 2008 and 2011) are supposed to be priced by both ends of the yield curve as the “maestro” tried to claim to Congress back in 2005.

The all-powerful Fed is said to control everything, from money to finance therefore interest rates which, we’re told, are as easy to manipulate at the push of a fed funds button. Independent rates would be more than a fly in the stinky Volcker Myth brand ointment; destroying their credibility in several key ways.

There never was a taper tantrum celebration last year leading up to this year, meaning the independent part of the curve(s) has indeed been acting independently, consistently rejecting the justification for taper then rate hikes from the very beginning. It still is rejecting them now, thus ongoing inversion.

Fed pressure keeps pushing up front, but it doesn’t dent the resolve – the recession risk resolve – at the long end no matter how the ST USTs refigure whichever new rate hike rationalization. What I said in January still applies, the conflict of interest rates as conflicting as ever:

With no 2021 or yet 2022 landmine, the yield curve is actually two curves again waiting for this clash or conflict of interest rates (thanks Mr. Tateo for suggesting this title) to be settled one way or the other. Balance of probabilities in the front are more favorable, yet still so much unappreciated negative potential keeps a lid on it at the back.

Those front probabilities had been looking soft in that interim between late April and the European decision end of May. The upturn potential for crude rebalanced the consensus if only in that part of the curve.

The only factor which has changed over the sixteen months since Fedwire is the Federal Reserve. Not whether there are real slowdown now recession risks to the global economy, rather how far and for how long the FOMC will be able to go before those become too immediate and desperate to finally, maybe inevitably supersede these new boosted CPI politics.

Despite new highs for the CPI, inflation or even growth potential hasn’t budged an inch. Not just in recent months, but, again, since last year. The question insofar as the independent curve is concerned, where the series of one-year forwards breaks down in reality, it’s entirely about when this rate conflict gets settled.

Not how.

Even swaps confirm that much is settled.

Stay In Touch