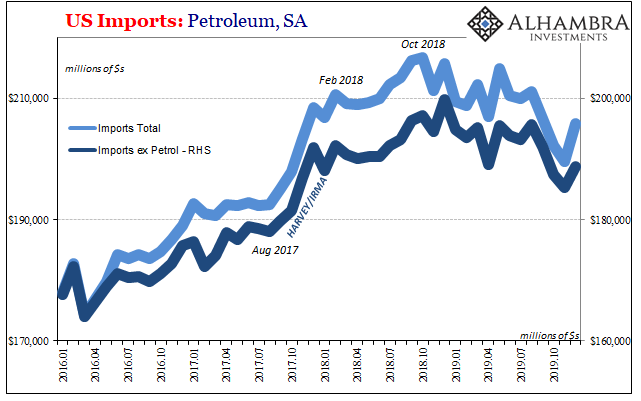

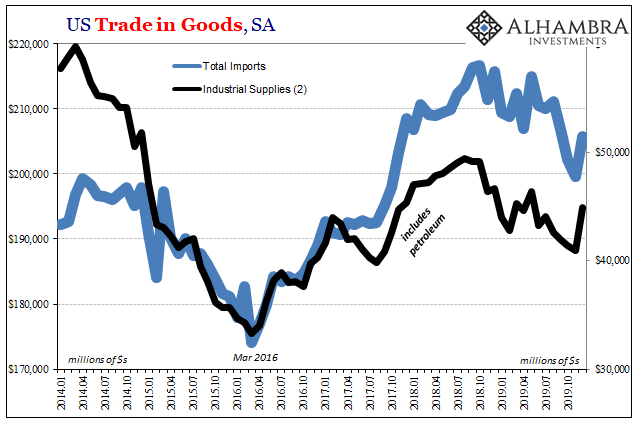

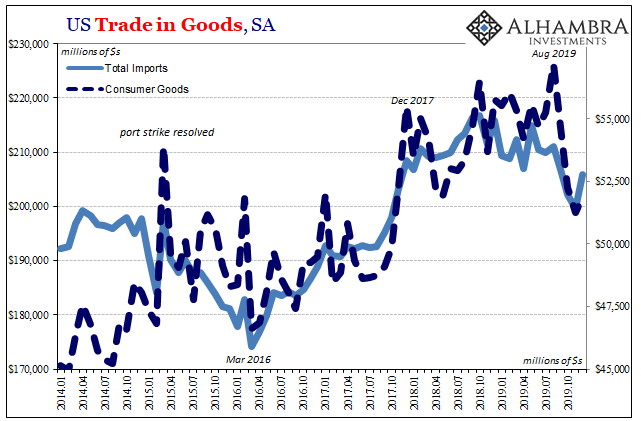

After a stunningly bad October and November, the Census Bureau reports US imports rebounded in December 2019 on a seasonally-adjusted basis. Having fallen below $200 billion for the first time since October 2017, total imports of goods rose to $205.8 billion in the final month of last year. However, most of that increase, two-thirds of it, was due to “industrial supplies” meaning crude oil.

The benchmark WT price had been, on average, $59.82 in December compared to $56.97 in November and $53.96 in October. The higher price along with slightly higher volumes meant that imports of petroleum rose faster and farther than everything else included in the overall monthly totals. Excluding oil, the total value of imported goods was $188.8 billion, only slightly higher than October (and still well short of September).

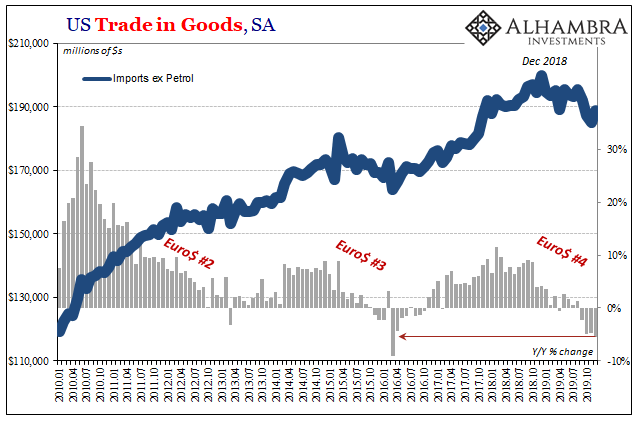

On a year-over-year basis, the level in December 2019 was 4.3% below the level from December 2018 (seasonally adjusted; -2.3% unadjusted). When excluding oil, however, the contraction increases to 5.5% year-over-year.

Not only is that the worst monthly change of Euro$ #4 it represents the second worst result in the last ten years; only March 2016 at the very bottom of Euro$ #3 had a greater decline.

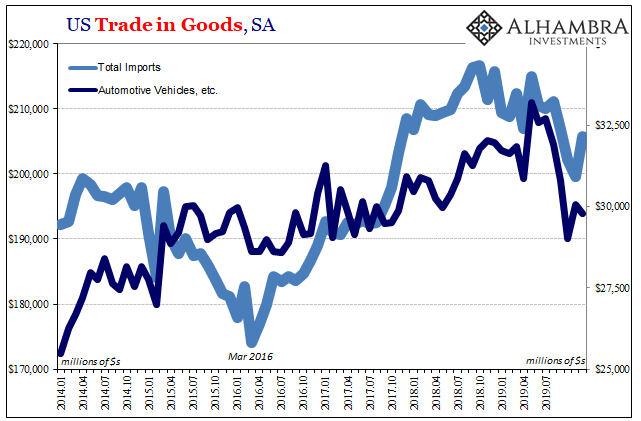

This would suggest that underlying US demand for goods remains subdued, to put it mildly. The other categories for imports show only small gains in December after the last few months of large setbacks. In automobiles, for example, the Census Bureau believes that just $29.8 billion worth of vehicles were imported during the month of November, barely more than the $29.1 billion which had been brought in during October.

October’s level for inbound cars and trucks had been the lowest since August 2016, and about the same as the monthly totals from early 2015 – five years ago.

In the broad category of consumer goods the total for December was just $655 million better than the $51.2 billion from November. That prior month had been the lowest since October 2017.

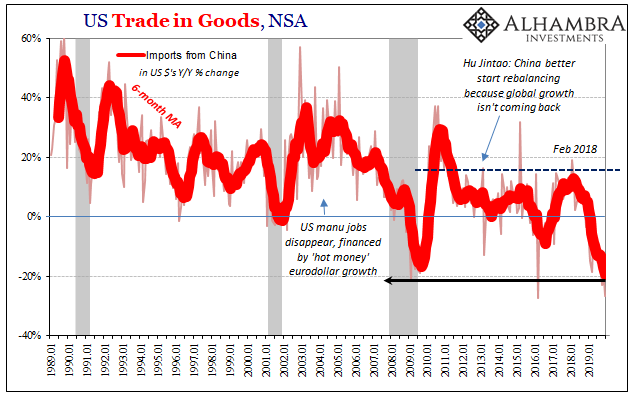

In terms of geography, the trade wars continue to plague demand for Chinese-made products. As expected, as well as intended, we are starting to see record numbers which, from the Chinese perspective, is an unwelcome development (contrary to the Chinese numbers). The Census Bureau reports that year-over-year imports were down 26.8% in December (unadjusted), making the 6-month average -19.5% and the lowest in history.

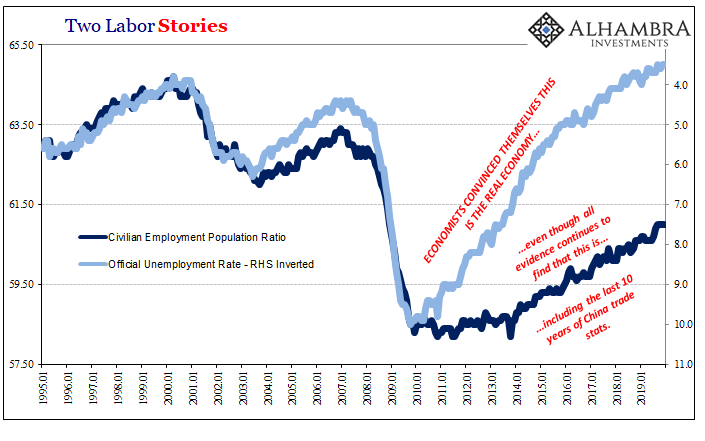

However you feel about them, the President’s protectionist policies have managed to exceed the Great “Recession” in terms of hitting China where it hurts the most. It is actually pouring pounds of salt in an already gaping wound, a sore spot that opened up at that time and never healed (because, contrary to the deliberately large number of references to the unemployment rate in last night’s State of the Union address, the US economy and its labor market have not come close being recovered, either).

China’s loss continues to be, for now, no one else’s gain. With the weak euro plied against the (re-)risen dollar Europe has been poised to benefit, but American demand has tailed off in that rush of the dollar’s disinflationary headwind. Imports from Europe rose just 3.3% year-over-year in December following a 1.6% decline in November – the first American minus for the European export sector since 2017.

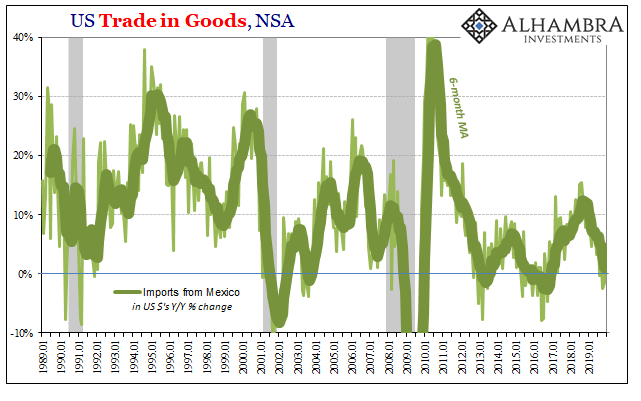

It was no better in and for Mexico, the one country which should have been raking in the boom during all of last year as demand for China’s produce tanked. Instead, imports from Mexico waned. The US took in just 1.9% more goods in the final month of 2019 than in the final month of 2018. The more important 6-month average is now down to just +0.9%.

Mexico as much as Europe or anywhere else clearly defines Euro$ #4’s more immediate effects. The rising dollar which should be turbocharging American demand for foreign goods made anywhere outside of China instead had become those mysterious global headwinds (or domestic cross currents, if you are like Jay Powell) which had turned the whole thing sour.

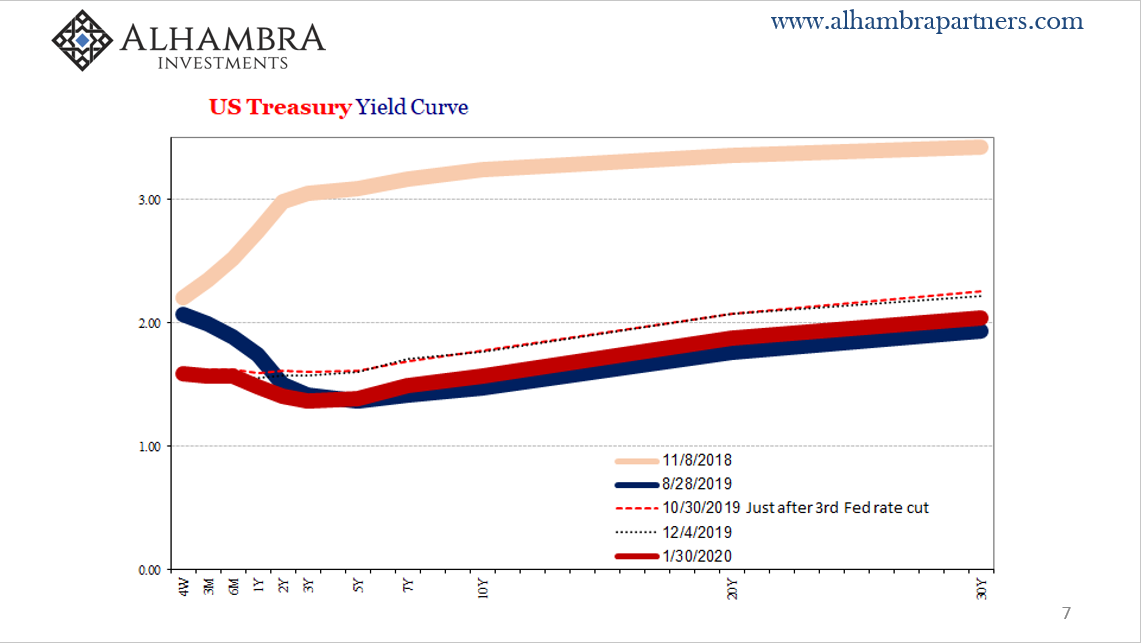

Remember, that was the message of the flattened curves in 2017 and early 2018 – more likely to sour than soar, there was too much risk the global dollar system would breakdown (again) leading to another (the fourth) worldwide downturn of uncertain proportions. It was only the last part which was captured by curve inversion(s) beginning late in 2018.

Given how oil prices traded in January 2020, there won’t be any boost to imports for last month. It’s not really oil prices and oil demand that we’re interested in analyzing; it’s the economic conditions for everything else. While it is possible the US economy has bottomed out, the December trade data doesn’t suggest anything better than small positive monthly noise.

If there had actually been an economic rebound going on, there would have been a whole lot more than WTI in the imports.

Stay In Touch