Inflation* in the US is falling rapidly with the CPI rising just 0.9% in the second half of 2022 versus 5.4% in the first six months. Existing home sales are down 14.6% in the last 3 months and 34% over the last year. Housing starts are down 22% and permits are down 30% year-over-year. Orders for durable goods are down 1.2%, exports are down 3.8%, and imports are down 4.3% over the last 3 months.

Real disposable income is up 0.8% in the last six months but was down 3.3% in the six months prior. Real (inflation-adjusted) personal consumption of goods is down 0.7% over the last year but real personal consumption of services is up 3.5% and services spending is 60% higher than that for goods. US payrolls are up 4.5 million jobs in the last year and there are still 10.5 million job openings.

Meanwhile, the Chinese have thrown caution to the wind and are attempting to re-open their economy after maintaining very strict lockdown procedures to control the spread of COVID for the last 3 years. The virus is now spreading rapidly and expectations for Chinese growth are rising but the Chinese New Year starts today and that will keep most factories shut for the next two weeks. In Europe, the economy is performing better than expected as natural gas prices have fallen back to pre-Ukraine invasion levels; inflation is falling rapidly there too. The economic outlook has improved so much relative to the US that the Euro is up nearly 14% since October. In Asia, the Bank of Japan is widely expected to end its practice of yield curve control and the Yen is rallying in anticipation, up 17% from its October low. Overall, the dollar index is down 11.3% since late September.

In Ukraine, there are rumors that Russia will start another offensive and try to take Kyiv this spring if not sooner. Belarus may or may not be involved. Europe and the US are still sending weapons to Ukraine but there is a debate about what kinds of weapons are lethal enough to help but not so lethal as to drag NATO into the conflict directly. In Latin America, there have been political riots in Brazil and Peru in the last month and Colombia has elected a leftist who openly fantasizes about nationalizing certain natural resources. Argentina is, well, Argentina just as Italy is Italy and Greece is Greece; none seem able to get anything right for very long.

What will be the impact on the global economy of the Chinese re-opening? How will the recent drop in the dollar impact US multinational companies’ earnings? How will the rise in the Euro affect inflation on the continent? Will the rise in the Yen and JGB yields affect the price of US Treasuries? When will the Japanese allow Chinese tourists to return? Exports from Japan to China have doubled in Yen terms since 2016 and grew through COVID. Will the reopening accelerate the pace of this trend? How much will the ongoing reorientation of global supply chains affect long-term Chinese growth? Will the shift of production to Mexico affect US immigration?

What about the recent revival of industrial policy in the western world? The US government is backing an expansion of semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the US despite the fact that we already have a shortage of engineers and workers to operate such facilities. Heck, we have a shortage of welders who might be needed to build the place. The Biden administration’s Build Back Better, CHIPS and Science Act. and the misnamed Inflation Reduction Act contain multiple provisions that support various favored (green) industries directly and indirectly. The Biden administration is also continuing the trade practices of the Trump administration and their limitations on exports of technology to China are, if anything, tougher. What is the impact on US growth, short and long term, from more government-directed investment and generally more government involvement in the economy?

And of course, we aren’t alone in pursuing policies that are intended to benefit domestic producers at the expense of our friends and enemies alike. European and Asian countries have long pursued these types of policies along with favorable currency policies to build trade and current account surpluses. The state of the US trade account is not solely a function of our own lousy fiscal policy, although our wanton profligacy certainly plays a large role. Many countries around the world are now restricting exports of what they deem critical materials, mostly foodstuffs.

The US and Europe are both planning to stockpile commodities and other goods believed to be of strategic importance. How will people in poor countries react to these artificial shortages? Will there be protests? Governments overthrown? What will be the impact on prices of those goods the government decides to amass and keep off the market? Will it affect production of those goods? Will some other goods, acting as substitutes, rise in price? Will some goods not be produced because of labor shortages or raw materials price distortions caused by the government purchases?

So, I ask you, with all that going on, do you really think you or anyone else can predict the course of the global economy? The above is just what I thought of off the top of my head; there are plenty more unknowns of the known and unknown variety. Do you really think anyone can, given all the data they request, produce an accurate estimate of future growth to the tenth of a percent? Or inflation? What about non-quantifiable inputs to economic growth? Is it only the things you can put a number on that count? What about Keynes’ “animal spirits”?

Investors spend an inordinate amount of time trying to figure out something that is beyond figuring. Their views of the economy and markets are shaped by current economic data and expectations regarding the future actions of a small group of economists who have no better chance of predicting the future than a coin flip. And their collective track record at such tea leaf reading hints that the coin might be the better choice.

Fortunately, investing does not require that you know the future. In fact, you’ll be a better investor almost immediately after you stop trying to know the unknowable. We have no control over the economy at all and trying to guess the outcome of all the interactions and feedback loops in our modern global economy takes time away from working on what we can control.

We can control our asset allocation. We can invest in companies with superior management. We can diversify our investments across multiple asset classes. We can control our spending. We can control the cost of our investments. We can observe the economy in the present and be aware of existing trends in markets. All of that is a lot of work and lot more valuable than trying to figure out next month’s payroll number. Don’t waste your time trying to do the impossible. Investing is already hard. Don’t make it harder.

*At Alhambra we don’t really think of inflation as most people do. We concentrate on the value of the dollar because it is much more important in the long run than mere changes in prices that may not be “inflation” at all. Inflation is a devaluation of the currency. Note that I didn’t say the devaluation causes inflation; it is the actual fall in the value of the currency that is inflation. What we’ve experienced in the post-COVID period – with a rising dollar – is rising prices, driven by a demand shock and, to a lesser degree, a supply shock. That demand shock was a result of a $5 trillion fiscal blowout, started by the Trump administration and continued by Biden. And given that the price hikes were driven by fiscal spending they will be permanent unless we have a fiscal retrenchment. Which doesn’t look likely. If the dollar continues to fall, as it has since September, we will just be adding inflation to the already elevated price level.

Environment

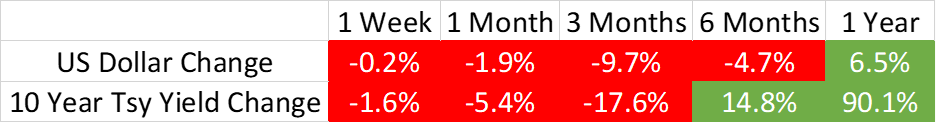

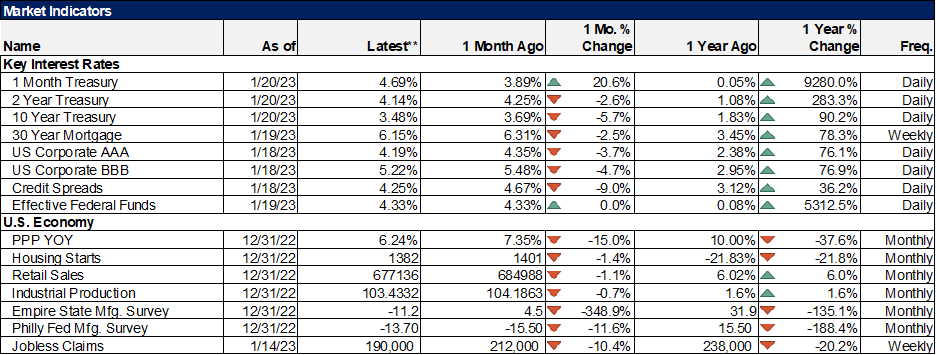

The 10-year yield and the US dollar were both lower on the week as US economic data continued to weaken. Short-term trend is still down on both and both are on the verge of breaking their intermediate-term uptrends; the dollar may already have done so. We have not made any changes to our portfolios yet but the temptation to extend duration (buy longer-term bonds) is nearly overwhelming.

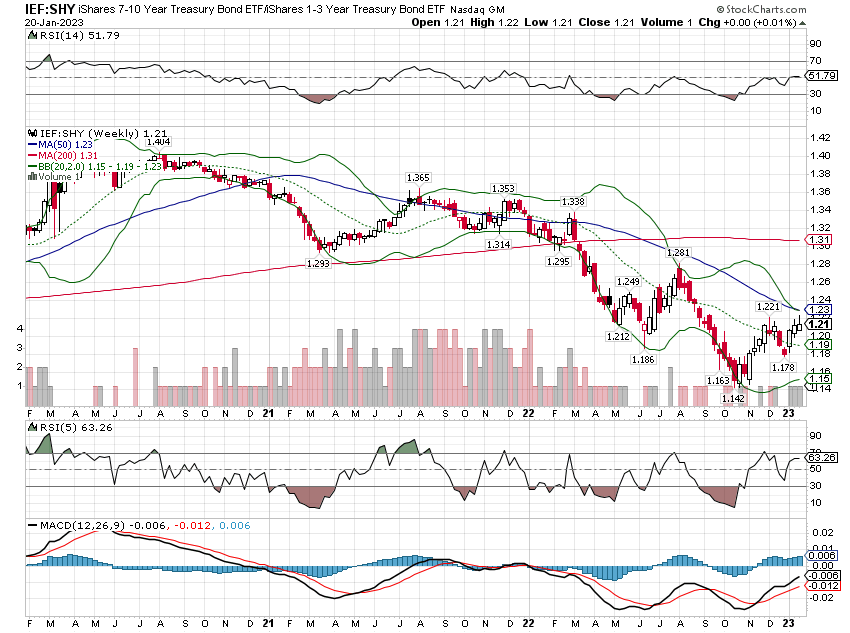

Everyone wants to buy bonds right now because everyone knows the US is headed for recession. But neither the 10-year, the 2-year or shorter-term yields are currently falling at a pace that we would expect just prior to recession. I would also point out that if we are headed for recession, the right trade is to buy long term, not the short end where everyone and his brother is currently buying. It is so easy to look at the inverted yield curve and just assume that buying the higher-yielding paper is the right thing to do – and it probably isn’t. In the lead-up to the COVID recession (yes, the markets were throwing off recessionary vibes prior to COVID), rates peaked in October of 2018 and bottomed in July 2020. Here’s the performance of SHY (1-3 years), IEI (3-7 years), and IEF (7-10 years) over that time:

If we go into recession you’ll make more by buying long-term bonds – duration matters for total return. When rates start to fall in anticipation of recession, the longer-term bond generally outperforms even if the short rate is falling faster. Duration matters for total return; the extra capital gain more than offsets the lower interest payment.

Buying the shorter-term notes and bills right now is actually more a bet on a soft landing or no recession scenario. Better-than-expected growth is probably the only way the shorter-term paper outperforms. I suspect most people buying T-bills right now don’t understand that’s the wager they’re making.

We sliced this little Gordian Knot by concentrating our bond portfolio on the middle or intermediate part of the curve. If you can’t predict the outcome – if you don’t know whether we’ll have a soft landing or hard or none at all and nobody really does – then the only logical bet is to not bet. Wait until the market answers the question. Right now, the trend is still down for long duration vs short. Here’s the 7-10 year index ETF (IEF, Alhambra owns) vs the 1-3 year index ETF (SHY, Alhambra owns).

Yes, there is a short-term uptrend but the longer trend is obvious. Breaking above the 50-week moving average that has proved a limit in the recent past would be a positive development and probably warrant shifting more toward the recession camp. But as with so many things today, we aren’t there yet.

The dollar, on the other hand, appears to be breaking its intermediate-term uptrend:

The dollar is now essentially unchanged since May of 2022, 7 months ago. Looking back a little further it is unchanged since March of 2020, nearly 3 years ago. The best that can be said is that over the last three years, there is no trend, call it neutral. So, we now have a short-term downtrend, a neutral intermediate-term trend, and still a long-term uptrend. To me, that means you have to continue to tilt toward a weak dollar portfolio.

The dollar will rally at times even when it is in a downtrend and it may be near such a move today. But for now, the short-term trend is down and the short term is getting pretty long.

Markets

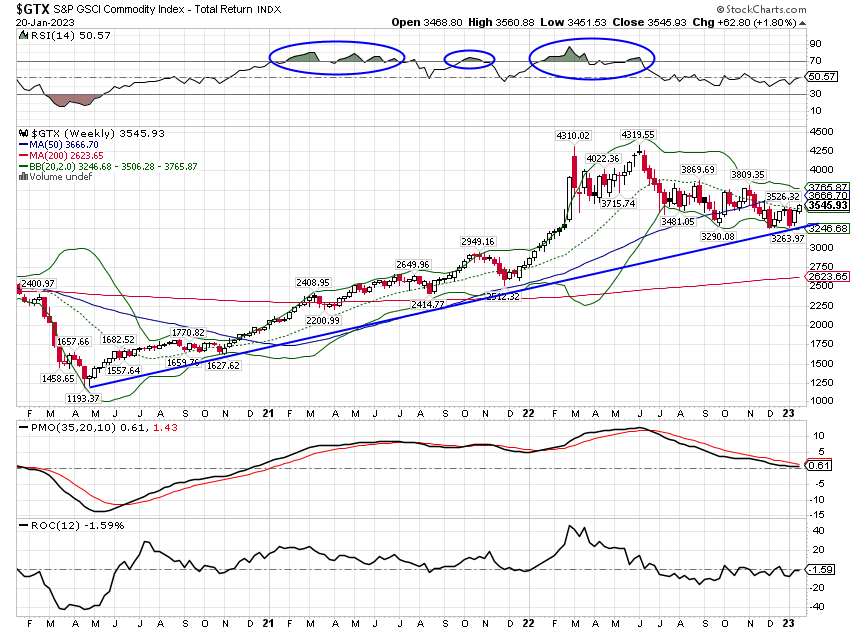

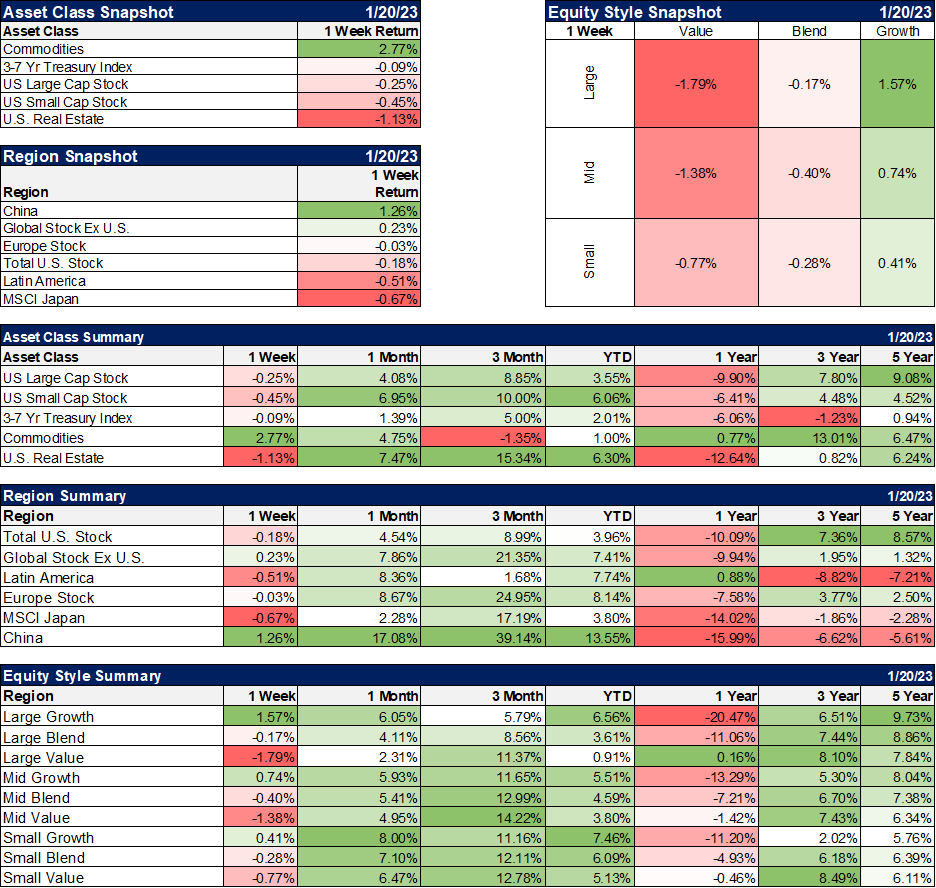

The only asset class we follow that was up last week was commodities, mostly due to crude oil which was up 2.2%. Gas prices were up by 4.1% and copper was also higher. Commodities peaked with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of last year. The GSCI has spent the last 10 months consolidating those gains. If the dollar continues to weaken, the index seems likely to resume its emerging long-term uptrend.

Growth stocks outperformed last week but are still well behind value over the last year. The valuation gap between value and growth remains very wide and I think there is a long-term shift toward value underway, especially if the dollar continues to fall. Value stocks tend to outperform in weak dollar environments.

Real estate was down last week and is the worst performer of the major asset classes over the last year. REITs are in a short-term uptrend though and last week didn’t change that.

China was higher on the week as the re-opening trade continues. Chinese New Year starts this week so there’ll be a dearth of news for a while. Don’t be surprised if the bulls take advantage of the lack of information to continue bidding stocks up. No news is good news.

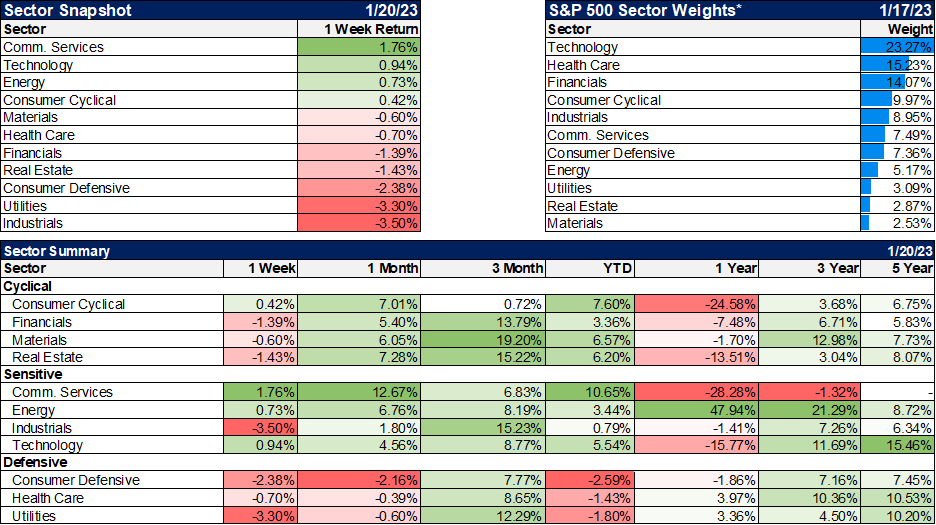

Communication services was the best-performing sector for the second straight week, continuing to recover from an awful year last year. It is still the worst performing sector over the 1-year period. This is now a very tech-heavy sector with the largest weights in Meta and Alphabet.

Technology was also up last week and while I’m not favorable toward the sector as a whole, I am starting to see some reasonably priced names in the sector. Growth is still expensive but not nearly as much as last year.

Economy

Retail sales, housing starts, and industrial production all pointed to weaker growth as did the Empire State and Philly Fed indexes, although Philly did improve to less bad. Jobless claims are still under 200k though and not in any way signaling stress or imminent recession. Credit spreads at 4.25% are below the long-term average of 5.4% and show little stress in junk bonds.

Friedrich Hayek’s Nobel acceptance speech in 1974 was titled The Pretence of Knowledge and in it, he lamented the modern “scientistic” nature of the economics profession. In a sense, he accused his fellow practitioners of professional envy of the hard sciences where concrete answers can and are found. 50 years later and economists and investors continue to pursue this false god of precision in a social science. There is a passage in the last paragraph of the speech that I think investors need to absorb. Hayek meant it for policymakers but it works quite well for investors too:

If man is not to do more harm than good in his efforts to improve the social order, he will have to learn that in this, as in all other fields where essential complexity of an organized kind prevails, he cannot acquire the full knowledge which would make mastery of the events possible. He will therefore have to use what knowledge he can achieve, not to shape the results as the craftsman shapes his handiwork, but rather to cultivate a growth by providing the appropriate environment, in the manner in which the gardener does this for his plants.

Substitute “his investment portfolio” for “social order” in the first sentence and you’ll see what I mean. We are limited in our ability to make tactical changes to our portfolios because we have incomplete knowledge. We can, however, develop strategies that have a high probability of success over our investment time horizon; we can cultivate the “appropriate environment”. We can make successful tactical changes but they will most often be based on psychology rather than any of the plethora of hard data available to the modern investor. Investing is hard exactly because it requires us to make decisions with only a vague sense of the odds of success. And more often than not, the right tactical decision is the one that makes us deeply uncomfortable. That’s why it’s hard to do and so few pull it off.

I have said repeatedly over the last year that the post-COVID economy is the most unusual of our lifetime. The best economic research will only yield a general, rather blurry view of the future. No amount of historical data will produce a prediction with any degree of precision. Just to give one example, a yield curve inversion gives warning of a recession sometime within the next two years. And it may not happen at all. Gee, thanks. If that’s the best the profession can do with loads of historical data what do you think it will produce in today’s unprecedented situation? My guess is mostly noise, with most of the useful insights coming from the heterodox side of the aisle.

Tune out the noise and concentrate on what’s important.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch