All my economists say ‘on one hand’ then ‘but on the other’. Can’t someone bring me a one-handed economist?

Maybe Harry Truman but on the other hand maybe Charles Frederick Carter or on the other hand maybe it was a one-armed economist

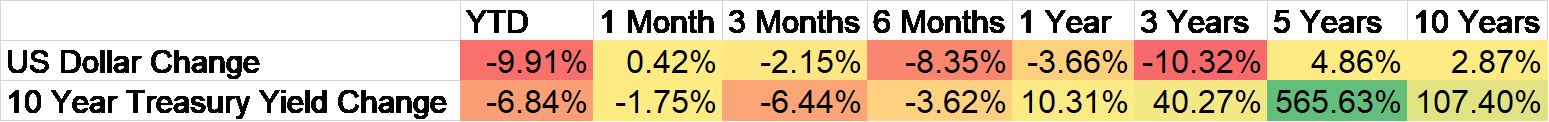

Jerome Powell’s speech at Jackson Hole last Friday was widely perceived as a capitulation, an admission that rate cuts are now necessary. Stocks soared with the Dow up 1.9%, the S&P 500 and NASDAQ both up 1.5% and more interest rate sensitive – or so I’ve heard – small caps soaring, the Russell 2000 up nearly 4%. Stocks whose fates are more tied to the business cycle were up the most with technology and communications services both lagging the market. The dollar was down nearly 1%. Stocks obviously loved the speech while the dollar rated it a negative.

Was it really that clear cut? If you read the first part of his speech, the part focused on Current Economic Conditions and Near Term Outlook, it sure doesn’t seem so. That 1100 word passage makes one yearn for a one-handed (or armed) economist or lawyer in the case of Jerome Powell. On the effect of tariffs on inflation, he says:

A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short-lived—a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, “one-time” does not mean “all at once.” It will continue to take time for tariff increases to work their way through supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates continue to evolve, potentially prolonging the adjustment process.

It is also possible, however, that the upward pressure on prices from tariffs could spur a more lasting inflation dynamic, and that is a risk to be assessed and managed. One possibility is that workers, who see their real incomes decline because of higher prices, demand and get higher wages from employers, setting off adverse wage–price dynamics. Given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks, that outcome does not seem likely.

Another possibility is that inflation expectations could move up, dragging actual inflation with them.

That is, I believe, three hands on the outlook for inflation. It also includes a Phillips Curve fallacy, the idea that a “tight” labor market is required for a wage/price spiral. I thought the 1970s drove a stake in that lousy argument – that more people working is what causes inflation – but apparently real world evidence is not sufficient to kill a line of thinking that is so handy for economists and politicians alike. The unemployment rate in the ’70s averaged 6.2% while inflation rose at an annual rate of 7.4%; you don’t need a low unemployment rate to get high inflation. In fact, the phenomenon runs the other way – higher inflation and rising wages lead to higher unemployment which is exactly what a non-economist, logical thinking person would deduce from simple supply/demand theory. He could have shortened the speech considerably by just saying, on the one hand we have no clue how tariffs will affect inflation but on the other hand we also have no clue how unemployment affects inflation.

Here is the passage that goosed the stock market:

Putting the pieces together, what are the implications for monetary policy? In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside—a challenging situation. When our goals are in tension like this, our framework calls for us to balance both sides of our dual mandate. Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago, and the stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market measures allows us to proceed carefully as we consider changes to our policy stance. Nonetheless, with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the shifting balance of risks may warrant adjusting our policy stance.

Those last 11 words were apparently worth nearly 1000 Dow points, which seems a tad excessive but on the other hand….

The more interesting part of the speech was the portion on the Fed’s Monetary Policy Framework in which the Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, commonly called the Consensus Statement, was revised from the one produced five years ago. This Consensus Statement is supposed to inform the public about how the Fed thinks about monetary policy in pursuing their mandates. Powell says:

In approaching this year’s review, a key objective has been to make sure that our framework is suitable across a broad range of economic conditions. At the same time, the framework needs to evolve with changes in the structure of the economy and our understanding of those changes. The Great Depression presented different challenges from those of the Great Inflation and the Great Moderation, which in turn are different from the ones we face today.

What is notable about this is that all of the “economic conditions” he cites – the Great Depression, the Great Inflation, and the Great Moderation – were all changes that caught economists off guard. In other words, there was no framework that economists could have developed prior to those events because economists didn’t think those things could happen. Indeed, the most recent bout of inflation falls exactly into that category. As Powell says in the speech:

At the time of the last review, we were living in a new normal, characterized by the proximity of interest rates to the effective lower bound (ELB), along with low growth, low inflation, and a very flat Phillips curve—meaning that inflation was not very responsive to slack in the economy….The economic conditions that brought the policy rate to the ELB and drove the 2020 framework changes were thought to be rooted in slow-moving global factors that would persist for an extended period.

The Consensus Statement produced in 2020 reflected what economists had “learned” during the immediately preceding period which proves nothing other than that economists are victims of recency bias just like the rest of us. What was the policy framework in that 2020 Consensus Statement? The main thrust of it was “flexible average inflation targeting” which in real life means that when inflation overshoots or undershoots the target, the Fed should then make up for that by allowing an overshoot in the opposite direction. If inflation undershoots the target – which is what the Fed was worried about in 2020 – monetary policy should allow inflation to overshoot so the long-term average stays on target. It should work in the other direction too; if inflation overshoots the target, monetary policy should allow inflation to undershoot to get the long-term average back down.

It sounds reasonable but there are some major flaws. The first and most obvious is that if inflation has been undershooting the target for years, as it had in 2020, how is the Fed going to get it to overshoot? If they’ve spent years trying to get it up to target and haven’t succeeded, writing a Consensus Statement saying that’s what you want to do isn’t going to change that. The other flaw is that pushing inflation below target is going to be very, very tough to do politically because it means lower NGDP growth – which politicians and citizens are not going to like. That is, in a way, being demonstrated today with President Trump wanting lower rates and the Fed resisting. Of course, we aren’t even down to the target so it shouldn’t be an issue yet but that hasn’t stopped the President from complaining.

If the Fed had followed this FAIT policy back in 2020/21 in the aftermath of COVID, we wouldn’t have had the huge surge in inflation that we did. Inflation was clearly above target and rising by the spring of 2021 but the Fed did nothing until a year later. Then, because they didn’t adhere to the policy framework they set in 2020, they had to push rates higher than would have been required if they started earlier. And that has them where they are today, with inflation still higher than the target and extreme political pressure to ease policy anyway. And so, now since they can’t stick to the old framework, they’re ditching it. It wasn’t the framework that failed, it was the members of the FOMC who had no confidence in it when COVID hit. The revisions Powell outlined could have been worse but what difference does it make if they don’t actually make policy within the framework they’ve defined?

Powell’s speech is, in my opinion, a reflection of the general state of economics today and across history for that matter. Economists are still arguing about the causes of the Great Depression and what ended it. The Great Inflation of the 60s and 70s is also still being debated. The Great Moderation saw economists breaking their arms patting themselves on the back, taking credit for something, it turns out, they had little to do with. Inflation fell for a lot of reasons from the early 80s all the way to 2020 but economists taking credit is like the weatherman taking credit for ending a drought.

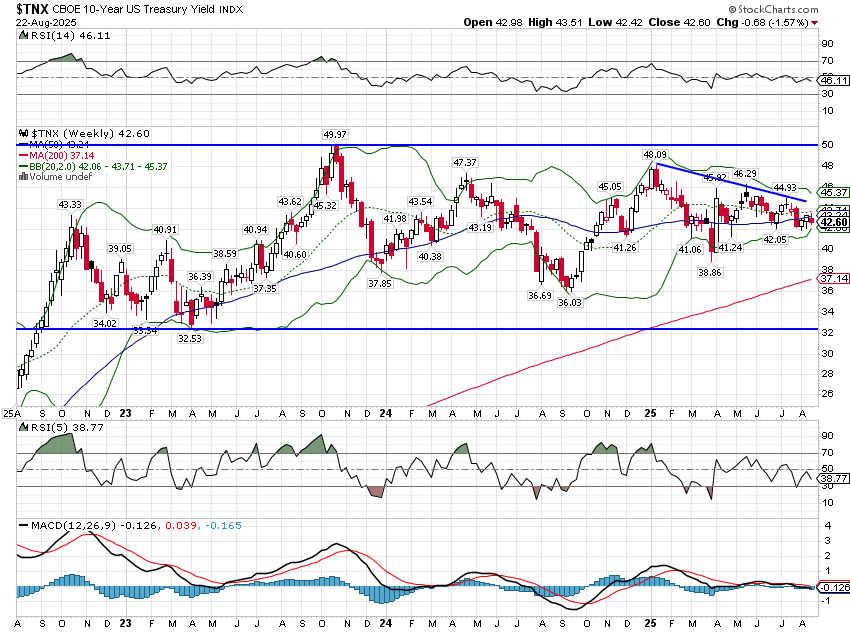

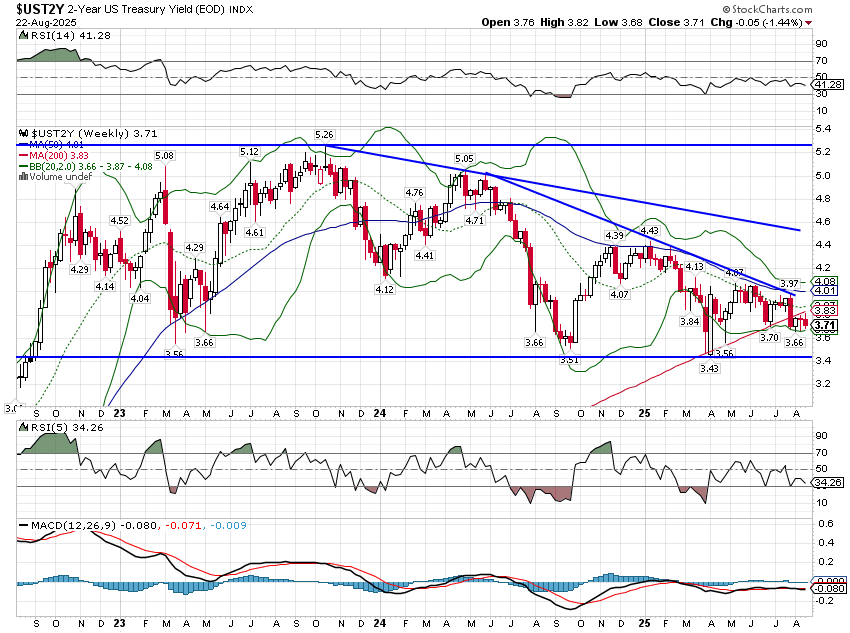

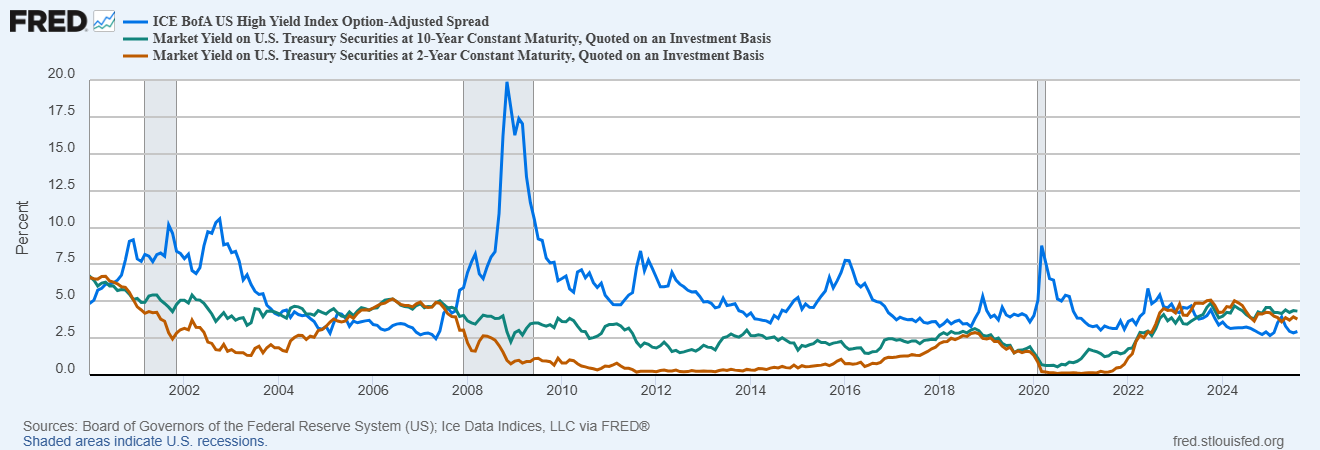

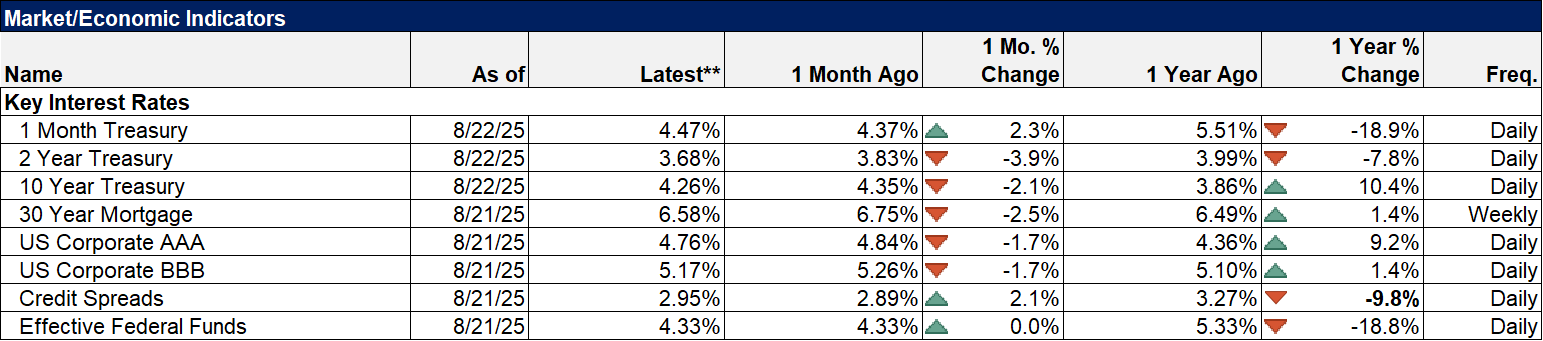

I would be quite careful about drawing any conclusions from what was said at Jackson Hole last week and the subsequent stock market reaction. Bond and money markets apparently didn’t hear the same speech as stock traders. The odds of a rate cut in September, at least as of Saturday morning on the CME’s Fedwatch tool, are lower than they were before the speech (75% vs 85%). Bond yields fell Friday but the move was pretty modest at 7 basis points for the 10-year and 9 for the 2-year. Those moves really aren’t very large – you can barely see them on the charts below – and rates are still above the April lows associated with Trump’s reciprocal tariffs.

The only part of Powell’s speech that I agree with is this short passage near the beginning:

This year, the economy has faced new challenges. Significantly higher tariffs across our trading partners are remaking the global trading system. Tighter immigration policy has led to an abrupt slowdown in labor force growth. Over the longer run, changes in tax, spending, and regulatory policies may also have important implications for economic growth and productivity. There is significant uncertainty about where all of these polices will eventually settle and what their lasting effects on the economy will be.

This is what I’ve been saying for months. We don’t know how all these new policies will interact and what the ultimate outcome will be. We don’t know if the positives of the tax bill – and there were certainly some – will offset the negatives of the tariffs, immigration policy and the uncertainty produced by President Trump’s impulsive nature. The best way to approach economic forecasting is with a huge does of humility. Economists have lots of hands for good reason.

Note: There are 400 PhD economists working for the Fed’s Board of Governors. There are a similar number working for the regional Federal Reserve Banks. That’s roughly 1600 arms and this new framework is the best they could come up with.

Environment

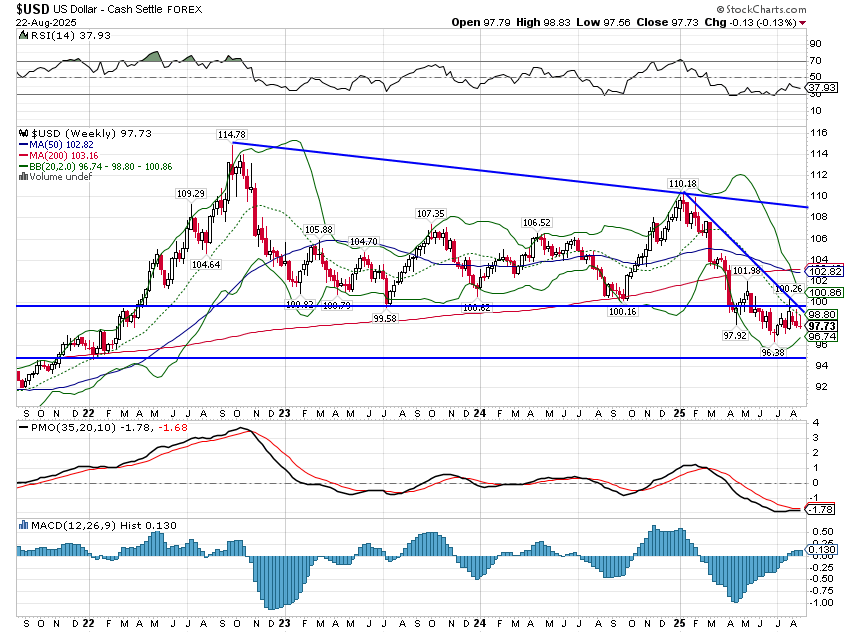

The dollar was on its way to an up week before Jerome Powell’s Jackson Hole speech but a few paragraphs from the Fed chief knocked nearly 1% off the buck in a matter of hours. I’ve said it many times – the President always gets the dollar he wants and this one wants a weak buck. With the President threatening to fire another Fed governor, I’m not sure it really mattered all that much what Powell had to say Friday. Whatever the case, the dollar remains in a short and intermediate-term downtrend. While a lot of people point to the dollar value as an indicator of future inflation, we don’t really think that’s the important factor for investors. For investors, the trend of the dollar is more important for its impact on capital flows and how that capital affects asset prices. A weaker dollar is generally associated with higher inflation but it isn’t the main factor. Consider that the dollar index is basically unchanged over the last 5 years while consumer prices have risen by nearly a quarter over that time.

The dollar index only tells us about the perception of the US economy relative to the other countries in the DXY basket. What’s interesting here is that the market perceives the US economy as getting weaker relative to the rest of the developed world. What does that tell you about the perceived impact of tariffs? And the old saying that perception is reality applies here. If capital flows away from the US to other parts of the world, it will positively impact growth in the places where that capital goes and negatively impact growth here in the US. It’s a relative change so that doesn’t mean the rest of the world will grow faster than the US – although that could be the case – but just that the relative difference is shrinking.

Having said that, I think we still need to be wary of a dollar reversal. Sentiment toward the dollar remains quite negative and it would not take much in the way of positive news on tariffs to reverse the perception of the US economy. Unfortunately, the President seems to be doubling tripling quadrupling down on obsessed with tariffs, announcing last Friday that furniture may face tariffs soon based on a section 232 investigation. Section 232 allows the President to adjust imports based on national security. You’ll have to ask the President how your choice of decor affects national security because I am at a loss.

Interest rates were also down on the week with most of the change coming on Friday. The 10-year is in a very short-term downtrend but the bigger picture is that it is still in the range its been in for most of the last 3 years. Despite a big stock market rally, growth expectations barely budged last week.

2-year yields were also down but like the 10-year remains in that 3-year channel. The 2-year appears to be pricing in about 2 rate cuts by year end. A lot can change in a short period of time though so we need to keep a close eye on shorter term rates right now.

Short-term rates and credit spreads is where we’ll get our first clues about an economic slowdown.

Markets

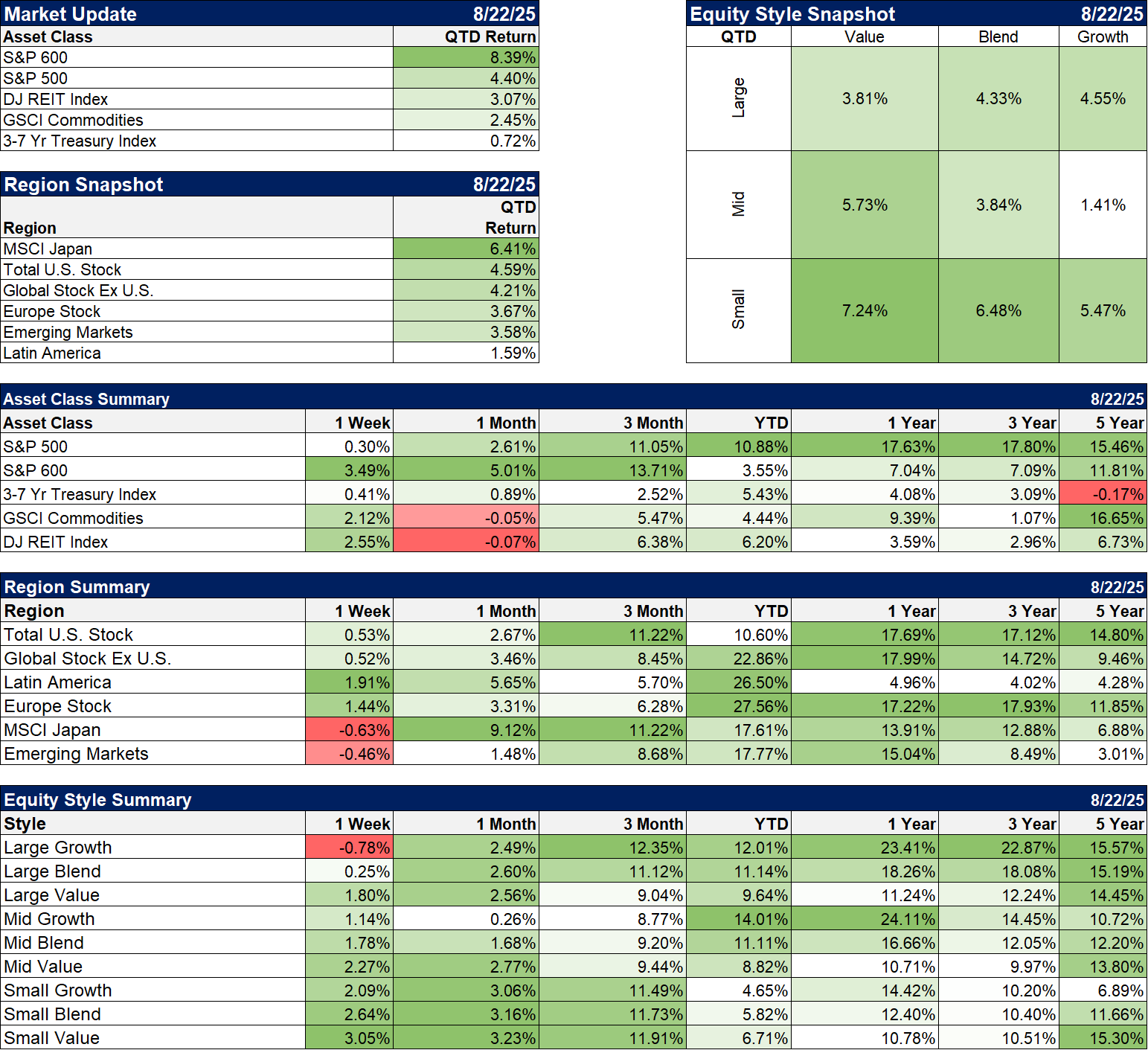

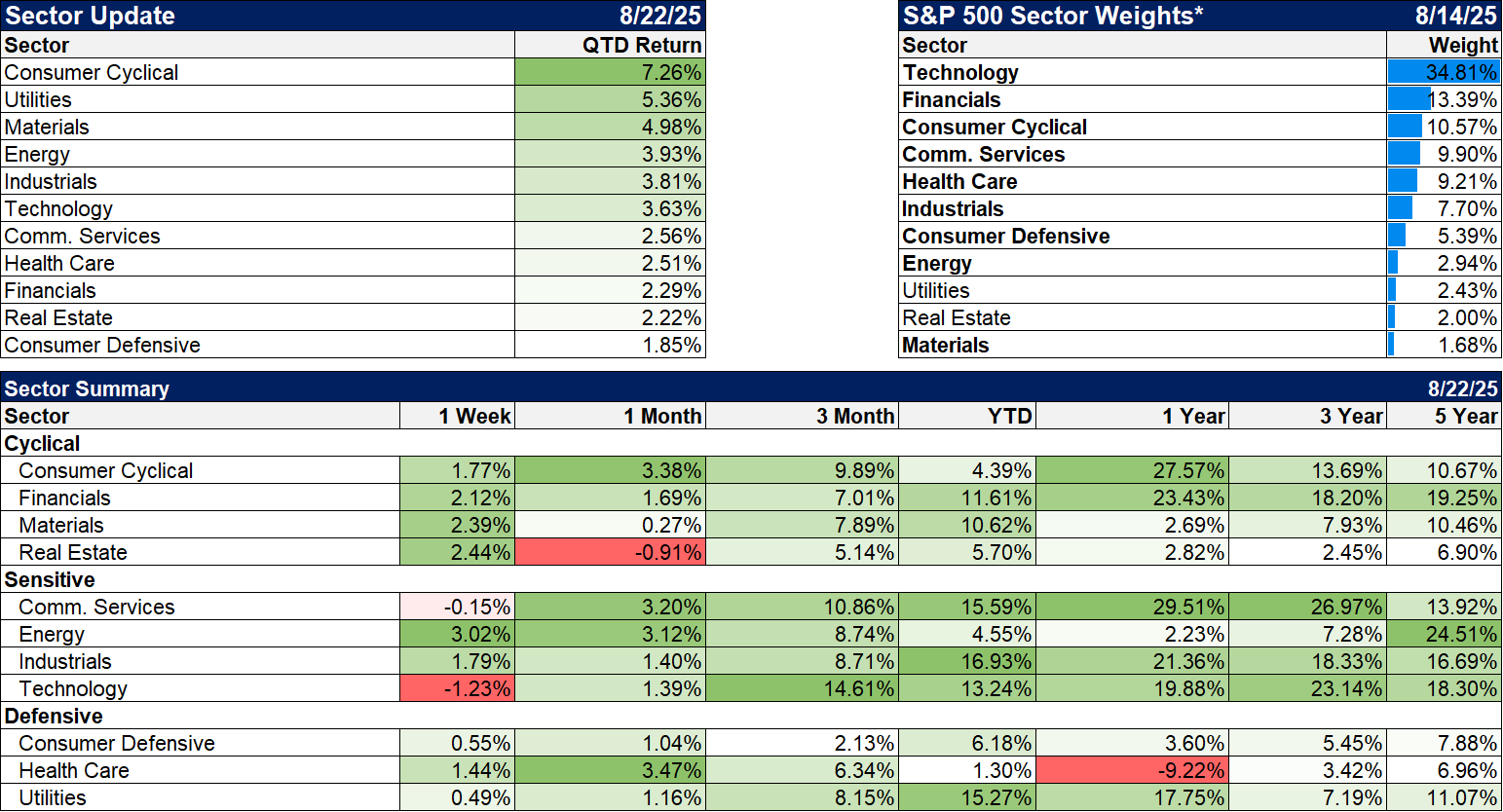

Friday was a very good day for stocks but the S&P 500 was only up 0.3% for the week. Small cap stocks had a good week but digging a little deeper reveals that it was really a value week. Large, mid and small cap stocks all outperformed on the week. I wouldn’t try to read too much into that from an economic standpoint. It’s one week and probably doesn’t mean anything.

Interest rates were down a little which gave REITs a tailwind and that could be the start of a better trend after being out of favor for most of the last 5 years. REITs perform better when long-term rates are falling but only if the economy stays out of recession. That might be a good cyclical bet but I believe the secular trend in rates has turned higher. REITs still provide diversification benefits in a rising rate environment but maximizing return may require a more active approach.

Sectors

Technology and communication services – which is technology adjacent – were the only sectors down last week. Those sectors also lagged on Friday while the winners were all cyclical to some degree. Consumer discretionary, energy, materials, financials, and industrials all outperformed the S&P on Friday and were also strong performers for the week. That’s a pretty clear signal the market believes that rate cuts will be positive for growth.

Economy/Market Indicators

Credit spreads were widening until Friday but narrowed with the stock rally. Spreads are still very narrow and credit offers essentially no upside in capital gains relative to Treasuries. You will capture a slightly higher coupon while you hold them but the big risk is a large capital loss when spreads inevitably widen. When that might happen is anyone’s guess.

Economy/Economic Data

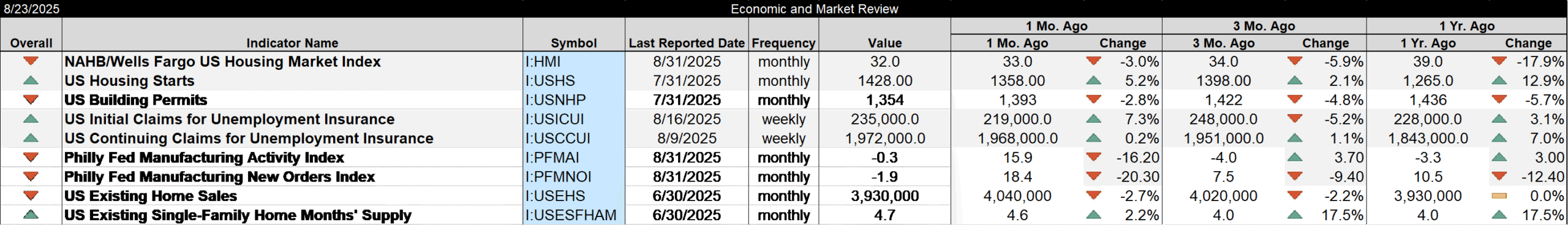

The economic data last week was pretty dull. The housing market index ticked lower but housing starts and existing home sales both ticked higher. The housing market index is interesting because in the past, a low reading was a good time to buy homebuilders and they have been perking up lately with the homebuilder ETF (ITB) up over 5% just on Friday and up 3% on the week.

The Philly Fed survey was much worse than expected with both the headline and new orders indexes dropping 16.2 and 20 points respectively. The employment index fell but remained positive. More ominous was the 8 point rise in the prices paid component to 66.8. Margins may be under pressure as the prices received index only rose 1 point to 36.1.

The S&P Global US preliminary PMIs were also released Friday and they contradicted the Philly report with the composite at 55.4, manufacturing at 53.3 (much better than expected) and services at 55.4. I’m not sure what to make of these reports as they also conflict with the ISM reports. The S&P version does survey a wider range of business sizes but is it possible that large companies are having a tougher time than smaller ones right now? Are larger companies seeing issues with exports that smaller, more domestically-oriented firms are not? Possible I guess but we need to get more evidence on that.

Stay In Touch