A bank’s assets triple over a few years when interest rates are low. The bank invests those assets in long-term, higher-yielding municipal bonds with little credit risk. Inflation flares up and interest rates rise, reducing the value of the municipal bonds and funding dries up. Regulators become concerned that the failure of this bank could damage public confidence in the banking system. Despite the fact that this bank is just the 50th largest in the US, regulators declare it “essential” and guarantee all deposits while the Fed and FDIC pledge to lend as necessary. The bank’s equity is written down to nearly zero and senior management is replaced.

Silicon Valley Bank? First Republic Bank? No, that describes the situation around Commonwealth Bank in Detroit – in 1972. Yes, we’ve been here before and no Silicon Valley Bank wasn’t bailed out because some rich people had accounts there. Commonwealth primarily served the African American community in Detroit. And Commonwealth isn’t the last time something like this happened. The Continental Illinois failure in 1984 also saw all depositors made whole due to the same concerns.

I wasn’t aware of the Commonwealth story until I read this article by historian Niall Ferguson yesterday. But I well knew the Continental Illinois saga – it was the largest US bank failure in history at that point – and the response by Paul Volcker, which was to continue his rate hiking campaign despite the bank failure. The Fed Funds rate rose from 8.5% in January of 1983 to 11.75% in July 1984. The year-over-year change in CPI had risen from 2.4% in July of 1983 to 4.9% in March of 1984 and fell to 4.3% by the time the Fed stopped the rate hikes in July 1984.

The yield curve back then flattened during the tightening episode but it did not invert, Volcker stopping with the 10/2 curve at 0.25%. The curve steepened after that as the 2-year fell from 13.2% to 5.9% in August of ’86. The 10-year fell from 12.9% to 7% over the same time. Inflation fell from 4.3% to 1.2% by December of ’86. There was no recession until 1990.

We could also look at the 1994 rate hiking episode when the Greenspan Fed nearly doubled the Fed Funds rate from 3% to 5.5% in 1994. Orange County, CA declared bankruptcy in December ’94 after it was revealed that their eccentric treasurer, Robert Citron, lost $1.5 billion betting the pension fund on lower rates. He was, through Merrill Lynch, borrowing short-term and investing long-term. When rates were falling he made high returns and other municipalities joined his pooled investment. As rates rose and the fund value fell, Citron said:

“The portfolio is not failing, has not failed, and will not fail,” Citron told The Orange County Register. “We have a liquidity problem which will be solved and no one will lose any principal — if the participants keep their funds in.”

Sound familiar? Well, they didn’t keep their funds in and Mr. Citron went to jail. The Greenspan Fed didn’t hike rates in December of ’94 (as was expected prior to OC) but did hike by another 50 basis points in January of ’95. They cut rates in July and again 2 more times by January of ’96. The yield curve never inverted, hitting a low of 0.15% in December ’94.

The Fed was hiking rates in all these cases because inflation was at an unacceptable level and rate hikes were used to slow the economy. In each case, the rate hikes eventually caused a crisis of some sort. Two involved bank bailouts – if you want to call them that – and one involved the biggest municipal bankruptcy in history at the time. And in all those cases the Fed continued to hike rates until they felt the inflation dragon had been slain. In none of those cases did we get a recession.

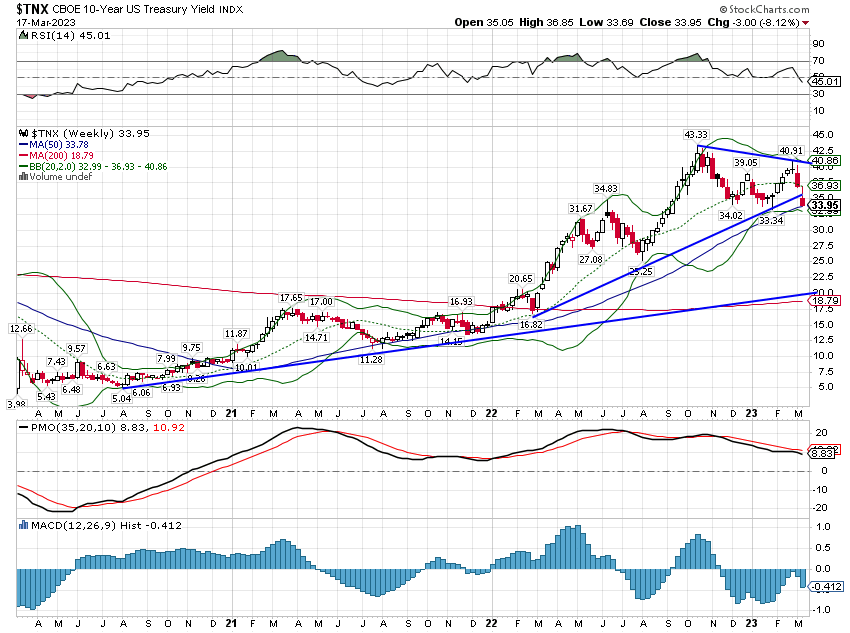

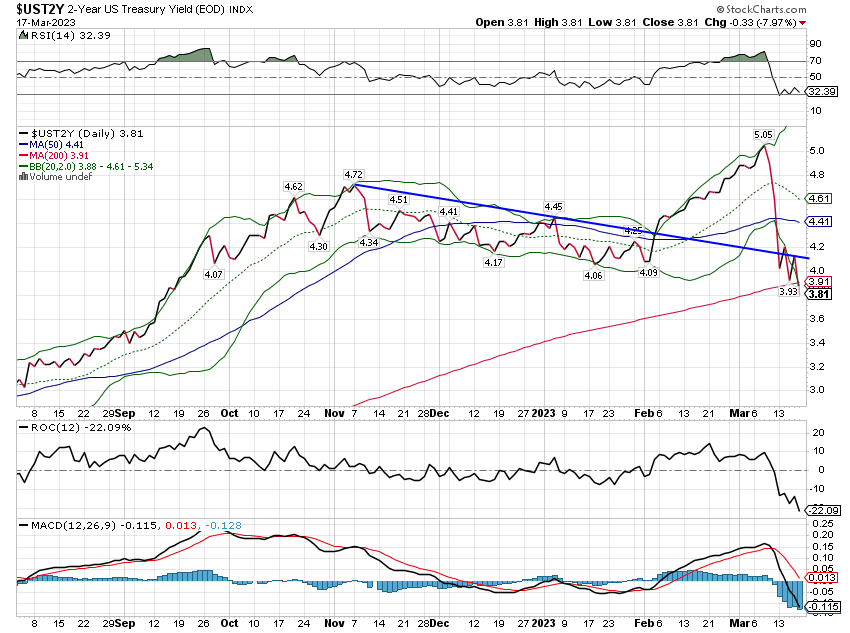

The environment today is certainly different so a no-recession outcome is probably asking too much of the financial gods. The yield curve is inverted and last week moved into a bull steepener – short rates falling faster than long rates – a condition that often occurs prior to recession. Since the 1980s, the start of the bull steepening phase comes about a year before the onset of recession and I don’t see any reason to think this one will be different. So, yes, the recession probably moved closer last week. How much closer is impossible to know, especially without knowing if there are more banking problems on the horizon.

This steepening of the yield curve also tends to come with a peak in interest rates. It is the steepening, not the inversion, that is the signal to start increasing the duration of your bond portfolio in anticipation of recession. The stock market playbook isn’t as obvious as the bond one but stocks do tend to keep rising after the steepening starts. In 1989, the S&P 500 rose nearly 22% over 10 months after the yield curve hit its low point. In 2000, the market rose 7.5% over 6 months, and in 2006 10.3% over 10 months. With sentiment very negative right now, I’d guess that if the bank situation stabilizes, we’ll likely see a similar rally, especially if the Fed also pauses the rate hikes.

Nothing we face today is really all that unique. There are differences obviously; history doesn’t repeat itself exactly. But assuming the worst is a recipe for an emotional decision and those rarely work out well. Stay calm, stick to your strategy, and make logical tactical decisions based on history.

Environment

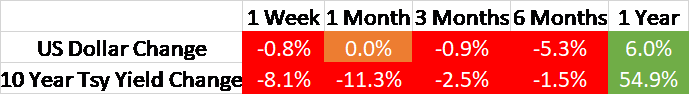

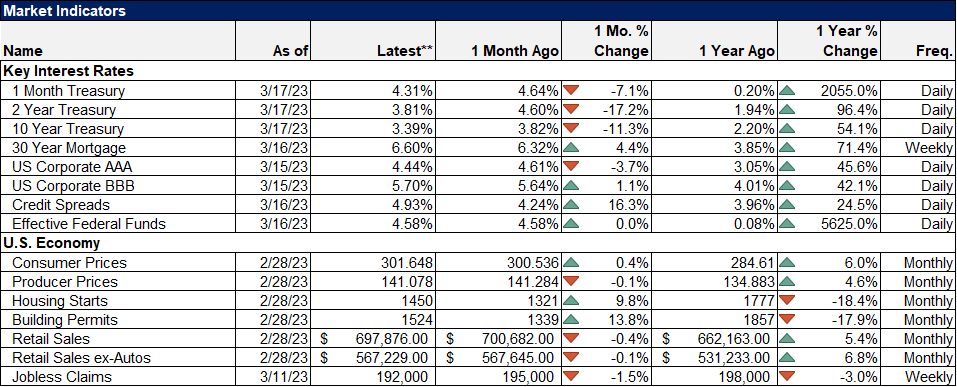

The trend of the 10-year Treasury note yield has shifted to down. Despite the drama in the banking sector, the change is still not that clear cut with the 10-year yield still above the lows of January and February. If there is some sort of resolution of the banking issues this week – and I don’t have any information that is the case – we could well see the uptrend resume. But for now, the short-term trend is down.

I’m also moving the 2-year yield to a downtrend although this is also a close call. The yield curve also steepened last week as the 2-year yield fell more than the 10-year (79 bps vs 30 bps).

The moves in rates last week, especially the 2-year Treasury, were among the biggest in history for such a short period of time. There are a lot of people pointing to these large moves as evidence of a lack of liquidity in the Treasury market, implying that there is something wrong with the structure of the market itself. I think there is a simpler explanation which is that there was a very large – unprecedented one might say – short position in the bond markets. When they all tried to cover, you got an epic move in bond prices. That isn’t a lack of liquidity driven by some issue with the market; it’s just what always happens when everyone gets on one side of a market and something shifts the narrative.

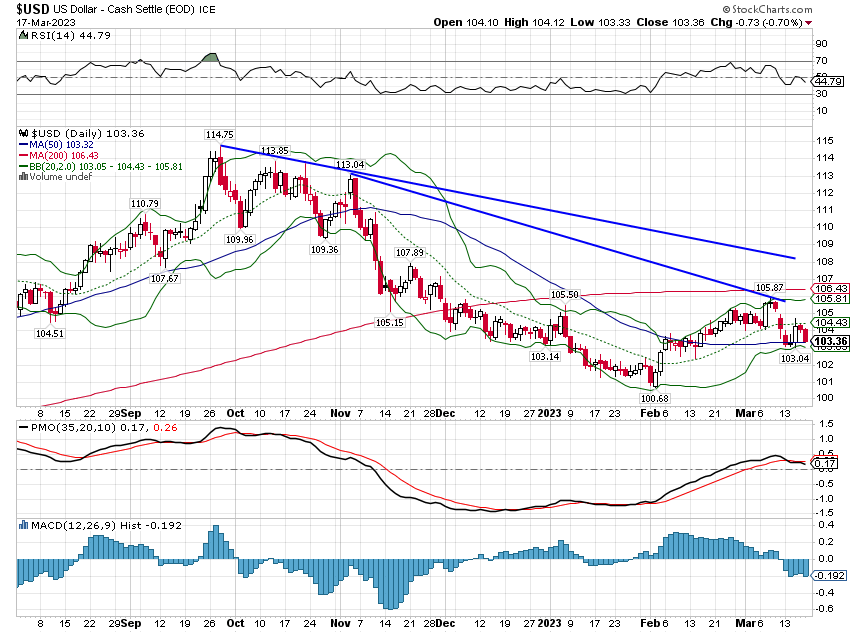

The dollar trend did not change; the buck is still in a downtrend. That is a bit surprising given that much of the angst last week came from Europe. The typical response would be a rush to dollars and Treasuries and while we got the latter we didn’t get the former. That is likely a response to the ECB raising rates by 50 basis points while the Fed is now expected to go 25 this week. We’ll see how long that divergence lasts.

Markets

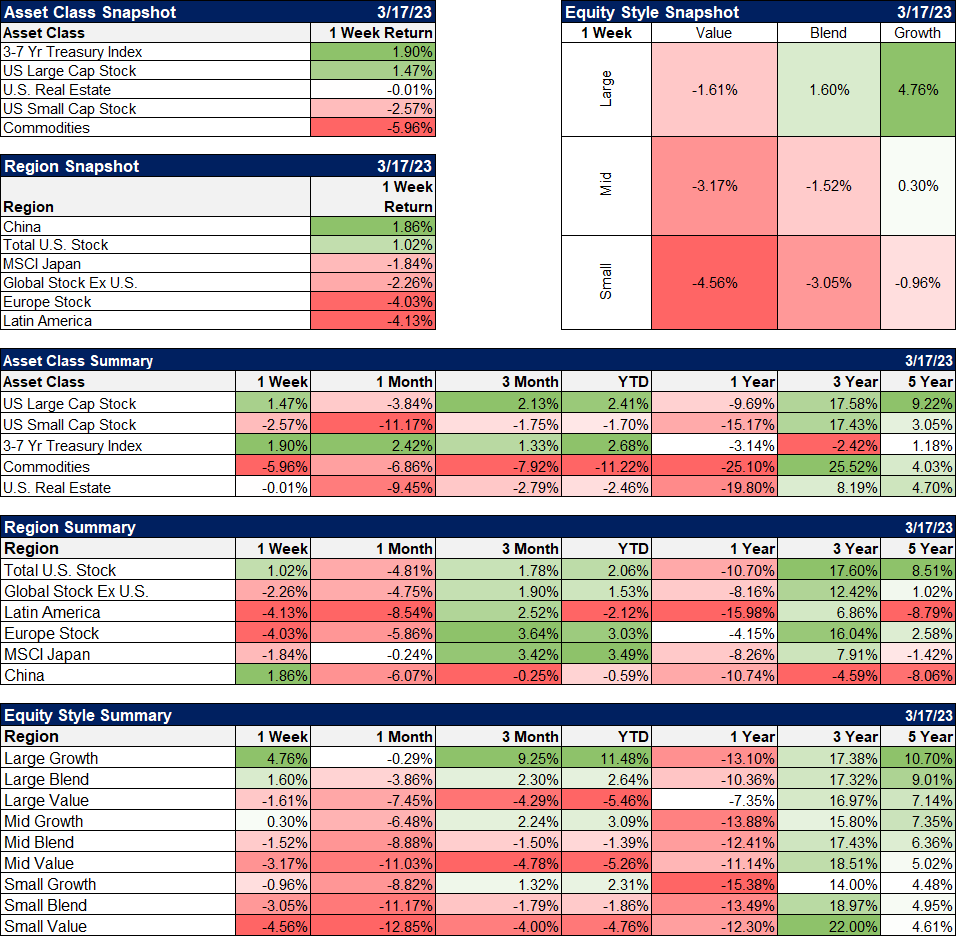

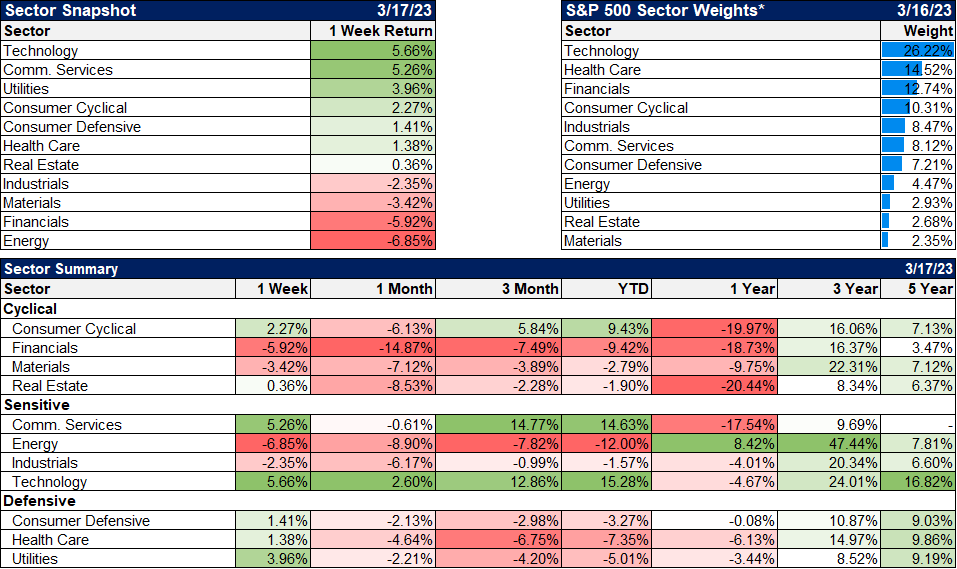

Despite all the turmoil in the banking sector, US stocks managed to post a gain last week but it was entirely due to the rise in technology and other growth stocks. There is – apparently – a belief that if we return to a lower-rate environment, growth stocks will return to their outperforming ways. Growth stock valuations have fallen some over the last year but no matter the interest rate environment, I don’t think they’ve fallen far enough to justify that belief.

The small-cap and value indexes fell more because they have a larger allocation to financials. Some of the fall is likely overdone though since “financials” isn’t just regional banks. I don’t think there is an issue with insurance companies or other financial firms.

Bonds were the best-performing asset class last week – not surprising – while commodities were the worst. That was driven by crude oil which fell 12.7% due to demand concerns. WTI crude continues to trade in a slight contango while Brent crude is in the normal backwardation configuration. That would seem to refute, at least on a global basis, the demand fears.

Precious metals did buck the commodity trend with gold up 5.7%. Platinum was also higher along with the grain markets. Copper fell 3.4% so the copper-to-gold ratio also fell, confirming the move in interest rates. It is, however, still above the lows set in October and July of last year. Recession fears are rising but apparently still less than last year.

US stocks did outperform last week as Europe and Latin America fell over 4%. China, like the US, bucked the trend and closed up 1.9%. Over the last year, Europe is still the best performer at -4.2% vs -10.7% for US stocks. Value is also still outperforming growth over the last year.

As noted previously, technology stocks were the big winners for the week along with communications stocks. The communications services sector is also heavily weighted to “technology” stocks as well with Meta (Facebook) and Alphabet (Google) accounting for 45.5% of the sector. Utility stocks also had a good week while energy and financials – both heavily weighted in the value indexes – were the biggest losers. Even after the loss, energy is still the best performer over the last year by a wide margin.

Economy

Credit spreads have widened during this banking uncertainty but are still below the peaks of last year and well below what we would expect in recession.

There was economic data released last week although it wasn’t paid much attention. Most of it was as expected but housing starts and permits were a big upside surprise. Like the banking crisis, much of what ails the housing market can be healed with lower rates.

As expected, consumer prices rose 0.4% in February and the year-over-year rate is now down to 6%. Producer prices actually fell by 0.1%, a much better-than-expected result and the year-over-year rate is now down to 4.6%. Import and export prices both fell by 1.1% and 0.8% respectively.

Housing starts and permits offered a nice surprise to the upside. Starts rose 9.8% from January to February while permits were up 13.8%.

Retail sales cooled in February, down 0.4%, after a blistering January when sales rose 3.2%. Ex-autos, sales were down just 0.1%.

And lastly, the preliminary reading on consumer sentiment from the University of Michigan showed a drop from 67 in February to 63.4 in March. The good news is that inflation expectations continue to fall.

As I write this Sunday evening, a deal has been announced by authorities in Switzerland for a purchase of Credit Suisse by UBS. A group of central banks, led by the Federal Reserve, have also announced a coordinated action to shore up dollar liquidity:

The Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Swiss National Bank are today announcing a coordinated action to enhance the provision of liquidity via the standing U.S. dollar liquidity swap line arrangements.

To improve the swap lines’ effectiveness in providing U.S. dollar funding, the central banks currently offering U.S. dollar operations have agreed to increase the frequency of 7-day maturity operations from weekly to daily. These daily operations will commence on Monday, March 20, 2023, and will continue at least through the end of April.

There are also reports that Warren Buffett has been talking to the Biden administration about the current US regional bank problems. What exactly they have been discussing is not known and probably won’t be until it is done. Buffett is known for getting deals done quick – on terms that are highly favorable to Berkshire Hathaway. During the 2008 crisis he provided funding for Goldman Sachs and Bank of America so he has experience with this sort of thing. And as of the end of 2022, he had nearly $130 billion in cash available.

I don’t know if these measures will be sufficient to calm markets and depositors, but if history is a guide, we’ll eventually find a way through. It would be ironic if Buffett plays a role again. The Federal Reserve came into being primarily because, after the panic of 1907, the government didn’t want to rely on one man – J.P. Morgan – to have to come to the rescue every time the bankers did something stupid. Here we are over 100 years later and it may well be the reputation of one man, again, that rescues the system from itself. Apparently, not much has changed.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch