One thing I can tell you for certain about last week’s big rally on Thursday and Friday: there were a lot of people who desperately wanted a good excuse to buy stocks. And buy they did after a better-than-expected CPI report Thursday morning, pushing the S&P 500 up nearly 6% on the week with all of that coming on Thursday and Friday. The same could be said of bonds which also had a good week, with the aggregate index up 2.3%.

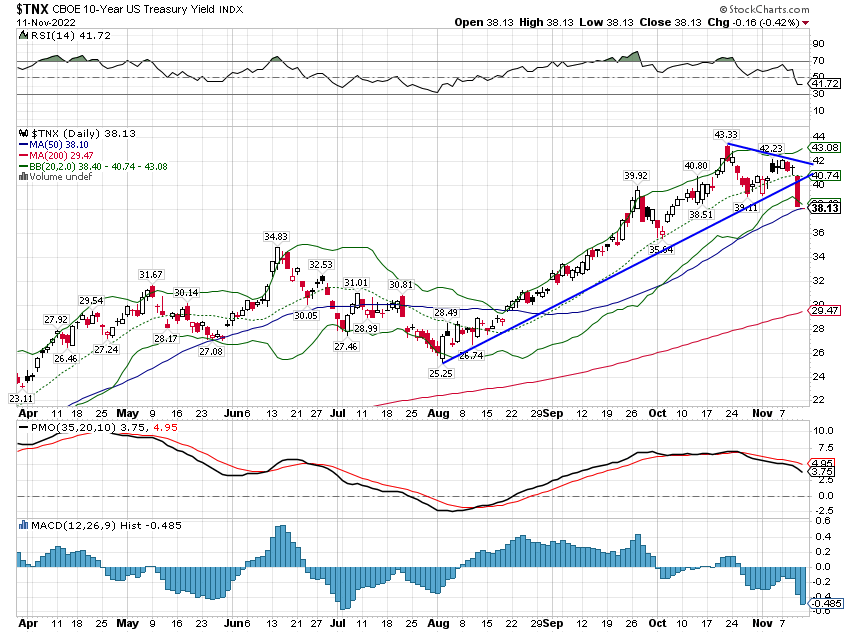

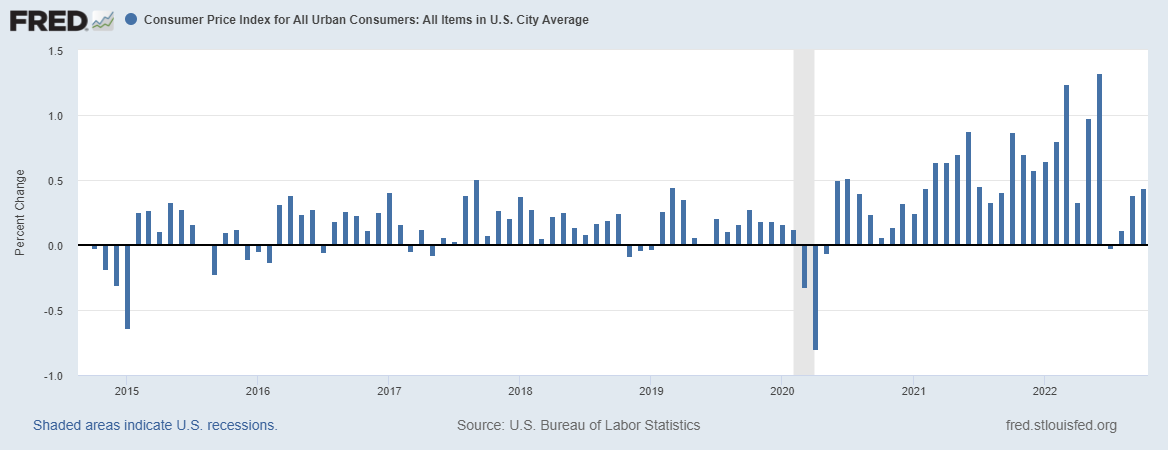

The stock market rally probably says more about the people doing the buying than it does about the reality of the inflation situation. The CPI report was indeed better than expected, especially the core reading of 0.3% which bested expectations of 0.5%. The headline rate was better too at 0.4% vs 0.6% expected, but it was also the fourth consecutive higher month-to-month reading. The compound annual rate of change in October was 5.4% while Q3 was 5.7% and Q2 was 10.5% so the change is in the right direction. But I can’t look at 5.4% inflation and say it’s no longer a problem.

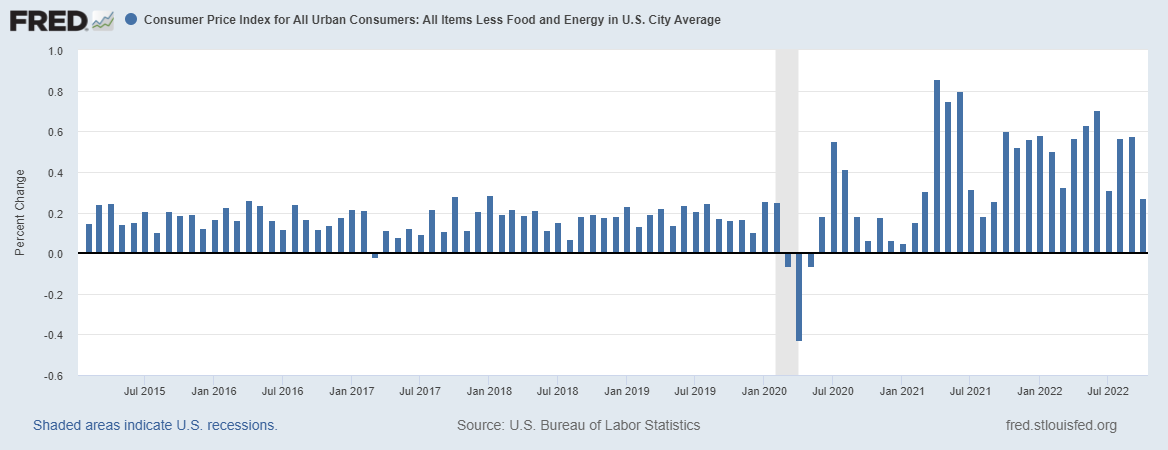

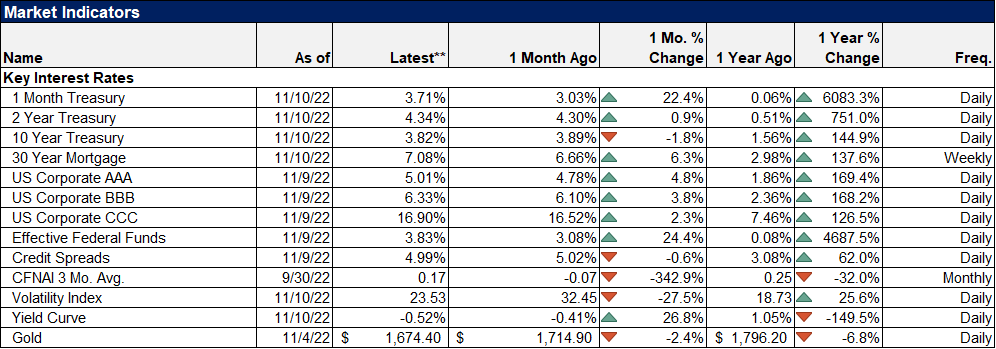

The drop in interest rates and the dollar last week reflects expectations that the Fed will moderate its tightening program and that may well be true. The odds of a 50 basis point hike in December are now at 83% which would bring the Fed Funds rate range to 4.25% to 4.5%. But the 3-month Treasury yield at 4.06% doesn’t even fully reflect that December hike yet and the 10-year/3-month curve is deeply inverted after last week. Based on Fed Funds futures, the market expects the Fed to keep hiking until hitting 4.75% to 5% by the March meeting and hold them there until cutting in November 2023.

The bond market, on the other hand, doesn’t seem to believe the Fed will be able to get rates that high. The 10-year rate at 3.81%, down from a high of 4.3% in October, indicates that the market is already looking for a further slowdown in nominal economic growth. And it isn’t just that inflation expectations are falling either; real rates fell last week too, just not as much as nominal rates. If the Fed continues to tighten policy from here, they are, I think, making a mistake, one that will be paid for by weaker growth. Whether it is weak enough to be called recession, I can’t say, but the inverted curves say the odds are high.

And this is where I have to throw a little cold water on last week’s rally. In past inflationary episodes such as the 60s and 70s, the stock market tended to bottom near the peak in inflation, and right now that looks like a good analogy. Inflation peaked in the summer and despite a minor undercut of the June lows for the S&P 500, stocks seem to be trying to find a bottom. The problem is that in those past episodes, the economy was already in recession when inflation peaked and the Fed was already cutting rates when stocks bottomed.

I think you can see the problem we have. Despite some slowing this year, we have not entered recession yet and the Fed is still in tightening mode. It would be unusual, to say the least, for stocks to bottom before the recession even starts. That would seem to imply that either we won’t have a recession or stocks need to revisit the lows. The first would mean the yield curve was wrong this time. The second might imply a need to hedge or make some other tactical move. I’d like the “no recession” option, please.

There is one intriguing possibility, one that could fit within the inverted yield curve narrative. We’ve heard a lot of talk recently about long and variable lags, the lag between a change in policy and its impact on the economy. That lag is best illustrated by the lag between a yield curve inversion and recession. That lag, depending on the curve, has in the past been as long as 2 years. If we get a lag of, say, 18 months before the onset of recession and inflation continues to moderate, stocks could rally back to near or even exceed their old highs before starting to discount a recession.

The question, of course, is whether we could get a sufficient lag for that to happen. I think so and I’ll give an example of how. The parts of the economy slowing the most are interest rate sensitive, with real estate the prime example. It seems logical that to get an improvement in real estate investment we need rates to come down but the Fed isn’t close to cutting. So could mortgage rates come down without the Fed cutting rates? Maybe.

The average 30-year mortgage rate was 7.08% last week through Thursday (Friday was a bank holiday). With the 10-year Treasury less than 4% that seems steep and it is. The average spread between the 10-year Treasury and the 30-year mortgage rate has averaged 1.7% since 1990 and now stands at 2.9%.

If the spread normalizes, mortgage rates could fall by 1.2% to 5.9%. That is still the highest rate since December of 2008, other than just recently, but it is consistent with rates from 2002 to 2008. We didn’t have any problems selling houses back then as I remember it.

The obvious question is why is the spread so high? Previous spikes were due to the 10-year rate falling during recession but this spike is different (like everything else in this strange business cycle). This spike appears to be due to expectations that the 10-year rate will keep rising at the current pace. In other words, it is predicated on continued Fed rate hikes. If that embedded rate hike fear premium disappears, if expectations for Fed rate hikes continue to moderate, the spread could easily fall back to normal. If that happens, I’d expect housing to improve and with it residential investment. Considering that residential investment has detracted from GDP for 6 quarters in a row, a reversal could be meaningful to growth.

That is just a plausible scenario for how recession might be delayed. There are others I’m sure. But I still think recession is the likely outcome of this rate hiking episode because history says that is the most likely outcome. But as I’ve been saying for quite a while now, this is a unique period in economic history. We don’t have a like period we can look back to and use as a template. We need to keep an open mind, expect anything and everything.

Environment

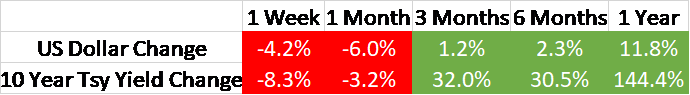

The upward momentum of the 10 year yield and the dollar finally broke last week; the short term trend is now down for both.

I want to stress that these are short-term changes and the intermediate to long-term trends are still up for both. How long that lasts, I can’t say, but the course of both will be determined by the future course of the global economy. It isn’t just the US economy that matters for these markets but also how we compare to the rest of the world. All else equal, if US growth expectations fall relative to European growth expectations, we would expect the dollar to fall and the Euro to rise. Of course, all else is not equal; just last week there were political changes, geopolitical changes, economic reports, and the collapse of the Bankman-Fried crypto “empire”. How much each of those contributed to the rapid drop in rates and the dollar is impossible to quantify but I have little doubt they all contributed.

I don’t think the short-term peak in rates and the dollar warrants any big changes to portfolios just yet. Any changes you make based on short-term trends should be small and with a tight stop. The moderation in core CPI is real but it isn’t rapid and the month-to-month change in headline CPI is actually up 4 months in a row. We are not out of the woods with inflation or the Fed. The short-term trend in rates and the dollar could easily reverse; it’s not time to be brave – yet.

Month-to-month change in CPI

Month-to-month change in CPI less food and energy:

One last comment on last week’s dollar move. I saw a lot of commentary last week about the speed of the drop, implying that something bad must be happening for it to drop so quickly. And especially Friday it seemed like every uptick found a seller, so it felt like something might be going on. But in cases like this never trust your gut; trust the data. And that data says that one-month changes like we’ve had so far in November are pretty common. By my cursory check, there have been at least a dozen months with a similar-sized drop since 1990. Most of the instances were of little note although one of those was the summer of 2008. But the move in 2008 was at the tail end of a multi-year downtrend for the dollar so much different conditions than today. I would also point out that Friday was a bank holiday in the US (Veteran’s Day) which may have had an impact on liquidity. In short, the dollar isn’t “collapsing” as I saw it put several times last week.

Markets

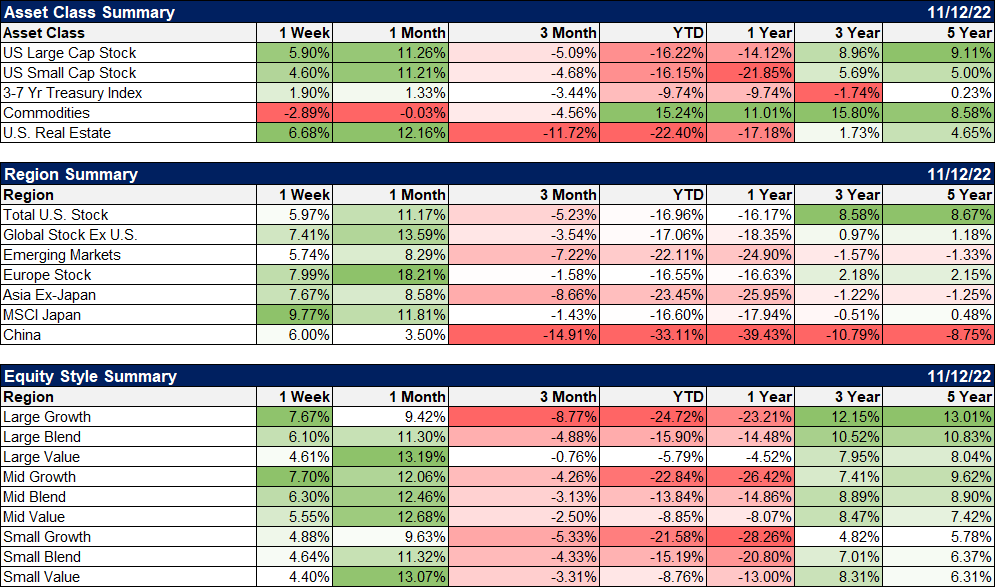

The most amazing thing about the rally in stocks last week is that US stocks were the laggards. Europe, Japan, China, Asia ex-Japan, Taiwan, Germany, Poland, Italy, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, South Africa, Colombia, and Chile stock markets all outperformed the US last week; which makes me think there was more going on that just a slight moderation of US inflation.

Non-US markets have actually performed pretty well this year considering what is going on. With all the issues faced by Germany from the Ukraine war, it seems a safe bet that their stock market must have fallen much further than the S&P 500. That was true if measured in dollars the DAX was down 40% at the low. But in Euros, the loss was 25%, exactly the same as the S&P 500. The difference, obviously, is the dollar. And now, even though the Euro has only recovered part of its losses for the year, the DAX is now only down 11% YTD. And it isn’t just Germany as the chart below shows. European stocks have basically matched the S&P 500 YTD and over the last year despite a big drag from the dollar. How do you think they’ll do if the dollar really does get in a downtrend?

What else could be driving stocks? The most obvious answer is that China appears to be concentrating finally on their economy. New changes to the COVID policy were announced over the weekend and the banks are being told to relax conditions on the housing market. I have doubts as to the efficacy of the housing measures but relaxing COVID restrictions could certainly have an impact on the global economy.

The less obvious answer is Russia’s ongoing failure in Ukraine. I do not pretend to know anymore than you do about what is going on there but it is pretty obvious that Russia is retreating. Retreating to where and why I don’t know but a map will suffice to see the territory they’ve given up in recent months. Strategic? It doesn’t look like it to me but I suppose that is possible in preparation for a long winter. It seems to me though that the most important development in the war may have happened in the US last week. There has been considerable concern in Europe that a Republican sweep would threaten a cutoff of aid to Ukraine. I’d say the results this week make that highly unlikely.

I don’t think the stock market rally of the last two months is particularly surprising. Sentiment reached a pretty dour place in late September and things can only get so dark. But sentiment has turned significantly more bullish in recent weeks and I’d be wary of chasing stocks higher here. We may not be headed back to the lows but a pullback to reset sentiment seems very likely. And remember, the S&P 500 is still in a downtrend, trading below its 200-day moving average.

Small and mid-cap stocks continue to look better technically than US large cap. The Russell 2000, S&P 600, and S&P 400 (midcap) index ETFs are all above their 200-day moving averages. But they did that briefly during the summer rally too so I wouldn’t say their downtrends are over yet. But they are getting very close.

Value underperformed last week but is still in an uptrend versus growth.

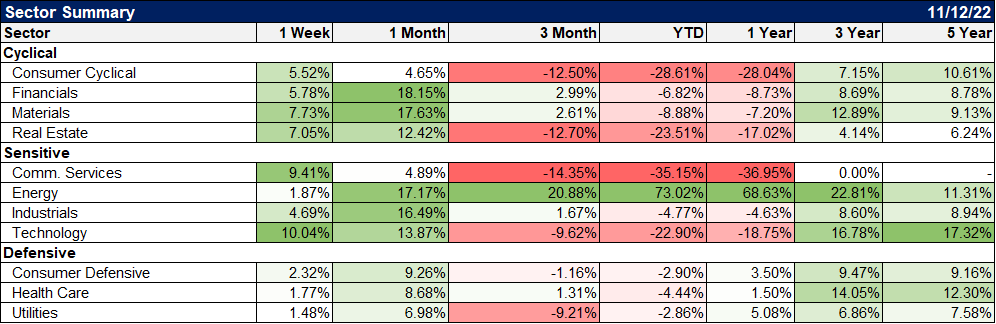

The most economically-sensitive sectors rallied the most last week. That is basically a bet on a soft landing, a bet that the Fed can kill inflation without killing the economy. As I’ve said before, I don’t have a lot of confidence in the Fed so it is hard for me to make that bet. I’d love to be wrong.

The drop in the dollar last week had a positive impact on gold which is a somewhat mixed blessing. We always have some gold in our portfolio so it was nice to see it not detracting from performance last week. But it isn’t a great indication about the future economy. Gold is essentially the anti-growth asset, rising when real rates and real growth expectations are falling. So far, the drop in real rates is less than the drop in nominal rates so the result is a slight drop in inflation expectations. But it isn’t all about inflation and that is worrisome.

It may have been just a matter of gold being very oversold though because other, more economically sensitive, metals were up too. Palladium, platinum, and copper were all up more than 6% last week. The commodity indexes were down primarily because of energy, with both crude and nat gas down on the week.

The economic environment is always hard to figure out but this cycle is more confusing than most. We’re in the midst of taming an inflationary outbreak that may be just an ephemeral aftershock of the COVID economic programs, fiscal and monetary. It is possible that all this really was transitory. I don’t think so but it is a possibility. If that is the case, then the Fed’s rate hiking campaign is going to look way overdone with the benefit of hindsight.

This could also be the beginning of a long period of higher inflation driven by factors such as demographics, deglobalization, and geo-politics. That’s what we believe. But we are also open to almost any outcome; our crystal ball has not cleared in recent months. We believe investors need to stay open-minded; expect nothing and you won’t be disappointed. Above all, in such an uncertain environment, stay diversified and stick to your strategy. There is some comfort in having a portfolio diversified across multiple asset classes, including some outside of stocks and bonds.

There’s plenty to do between now and the end of the year including tax loss harvesting, rebalancing, and reviewing your portfolio for ways to reduce costs. There are many ways to add value to your portfolio that have nothing to do with the Fed or the economy. Take care of the basics while we wait to see how some of these uncertainties are resolved.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch