We are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives.

Plan 9 From Outer Space

I have no idea what will happen this year. Neither does anyone else.

If this is your first time reading one of my commentaries, you should probably know that I say that a lot – I don’t know. The future is, as it always has been, inscrutable, impossible to know. Complex, chaotic systems such as the stock market or the global economy are not predictable, even by our new AI overlords. All we can really do is observe trends and have a good enough grasp of history to make some informed decisions. History can only be a rough guide so “informed” is not synonymous with “right” but the one constant throughout history is human nature. The things that motivate human behavior are not much different today than they were in ancient times. Fear, greed, selfishness, love, lust, social connection, ambition, aggression, compassion, cooperation, selflessness and, unfortunately, cruelty have been the human condition for millennia and that is unlikely to change. Our brains today are pretty much the same as they were 100 centuries ago and it is these recurring emotions, these themes, that created the past and will create the future.

It was these inherently human traits – lust for power, fear of the unknown, greed – that created the conditions, the environment, within which history evolved. And it is those same very human traits, along with some persistent cognitive biases – irrational decision making, our love of narratives (true or not) – that will create the future. The fear and greed we see in markets are a natural response to the events – natural and man-made – that shape the global political economy. And the fear and greed further influences events in a great feedback loop that ensures that the future isn’t static and predictable. So, no I don’t know what will happen in 2026.

Luckily, as I’ve said repeatedly over my many years of doing this, successful investing doesn’t require that we know the future. In fact, knowing the future might prove an impediment to success. Markets – humans – don’t always react to events the way we think they will or should. The crowd may see something you’ve missed – or miss something you’ve seen. Over short time frames – which in investing is anything less than about 5 years – investors can believe things – and bet on them in markets – that in retrospect look absolutely foolish. With the benefit of hindsight, we often call these episodes bubbles. Bubbles are hard to discern in real time because we can’t know what will look foolish in the future until we get there. If markets rise (fall) a lot for reasons that turn out not to be foolish, we just call it a bull (bear) market. It is interesting – at least to me – that we don’t have a word to describe when markets fall for foolish reasons. Are all bear markets based on rational analysis? Are there no periods which should be labeled “irrational pessimism”?

Which brings us to the question that’s on everyone’s mind these days:

I think you know what my answer is – I don’t know. And neither does anyone else.

What we do know is that the hyperscalers (Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Meta) are spending a lot of money on AI. Expectations for 2026 are for these 4 companies alone to spend nearly $500 billion on AI projects. Most of that is being funded by free cash flow although Meta has tapped debt markets recently. Other companies, such as Oracle, are also borrowing to fund much of their investment and for those companies AI better pay off on time. For the others, if AI doesn’t pay off as expected they will still have cash flow to invest in the future. What we don’t know is the degree to which AI borrowing is raising interest rates and potentially crowding out investments in other parts of the economy. It is also interesting that Apple isn’t spending on AI like the other members of the Magnificent Seven. While they are spending all, nearly all or sometimes more than all of their free cash flow, Apple is spending just 15%.

This investment, which amounts to about 1.5% of GDP – and could reach 2% this year – flows to the bottom line of the “picks and shovels” companies like TSM, Nvidia, Micron, Broadcom, Arista Networks and Vertiv Holding. These companies spread those profits around by investing in some of the other AI companies, like OpenAI, but also in new capacity and R&D. That benefits companies like KLAC, Lam Research, and ASML, semiconductor manufacturing equipment makers. All this investment is having an impact on the economy with Real Gross Domestic Private Investment rising as high as 19% of GDP, well above the long-term average of about 17% of GDP. But the investment is concentrated; investment in non-residential structures (which includes data centers) is down 6.3% over the last year while investment in information processing equipment and software has risen 15%. Investment in manufacturing structures, by the way, is down 9% year-over-year.

Is this massive investment a sign of a bubble? We won’t know until we find out whether it pays off – and when. One big difference between today’s spending and, say, the dot com era, is that AI investments are largely still coming from the existing cash flow of some of the country’s most profitable companies. That wasn’t the case in 1999 when the spending was mostly funded by debt and the IPO proceeds of companies with little or no profits. If this is a bubble, it is a more rational one than the late 90s dot com version. The interesting thing about “bubbles”, especially the ones driven by technological change, is that the underlying premise of the “bubble” is often correct. What is usually incorrect is the time frame and when the new thing doesn’t pay off on the market’s expected schedule, investors have to adjust. If the timeline is longer than expected, the prices of stocks and bonds have to adjust to that new reality.

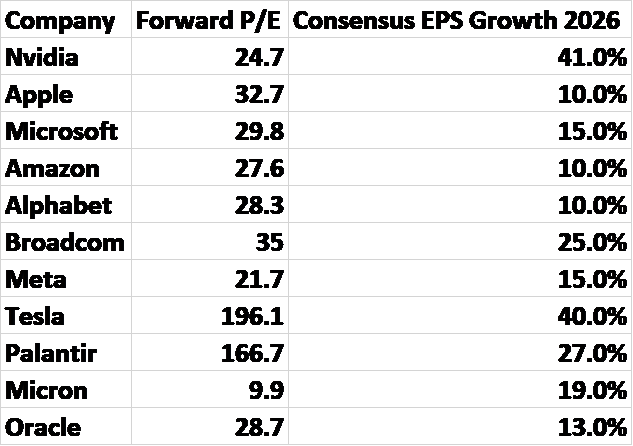

Will AI pay off in a timely manner? That’s the thing we don’t know but if past is prologue the answer is probably no. New technologies almost always take longer than expected to realize their promise. If stock prices reflect expectations of a quick payoff and it doesn’t come, they will, ahem, adjust. When we look at the stocks most affected by AI right now, we find that they are indeed expensive, but maybe not as expensive as you might think:

Of course, these are just the best guesses we have about how these companies will perform this year. And some of these are really expensive with P/Es much higher than their expected growth. But overall, I would say that the surprising thing here is that the valuations are high but not outrageously so. If this is deemed a bubble in the future it will likely be because AI didn’t even come close to living up to its hype.

For investors, the real problem is with the indexes which are normally used to fulfill the stock allocation of their portfolio. The top 10 companies in the S&P 500 are now 39% of the index and their high valuations have pushed the index P/E to 22.4, well above the long-term average. Buying the S&P 500, which was supposed to be “buying the market” has become a heavy bet on the future of AI. In an era of YOLO and FOMO, maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that the “safe” way of investing in stocks has become riskier.

While everyone is looking at AI for a bubble, I think the real bubble may be the gambling mentality that has infected markets in the post-COVID era (and maybe even starting earlier). The annual handle (amount bet) on sports in the US over the last five years has nearly tripled, up to about $164 billion in 2025. That betting mentality has infected markets too; stock trading, as measured by average daily volume of shares traded, has risen 27% over the last five years while the average holding period has fallen 40%. Options trading is up 40% over the same time frame and over half the daily trading volume is in Zero Days To Expiration options which are literally nothing more than a one day bet on the direction of a stock or index.

While the investment industry created this casino, they also created a plethora of ways to avoid it. Rather than own the capitalization weighted S&P 500, you can own the equal weighted version (RSP) or the revenue weighted version (RWL). These indexes trade at over a 30% discount to the cap weighted index while owning the exact same stocks. You can further diversify by owning a value factor ETF (VLUE) or an international value index ETF (EFV) both of which trade at even bigger discounts. The proliferation of ETFs over the last 30 years allows investors to gamble if they want (triple leveraged anyone?) but it also allows us to do things that were once only available to large institutions.

Maybe AI is all that its cheerleaders say and we’ll look back on this period as the beginning of a golden age. Or maybe AI is the biggest bubble in my 30+ year career in investing. I don’t know and neither do you. But not knowing and acknowledging that we don’t know means we aren’t tempted to make any big bets on it either way. And avoiding big bets means we also avoid big losses when we’re wrong. Remember, investing is a loser’s game; you win by making the fewest mistakes.

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

Maybe Mark Twain but probably not

Stay In Touch