It’s one of those things which everyone just accepts because everyone says it must be true. If the US$ is rising, what else other than the Federal Reserve. In particular, the Fed has to be raising rates in relation to other central banks; interest rate differentials. A relatively more “hawkish” US policy therefore the wind in the sails of a “strong” dollar exchange regime.

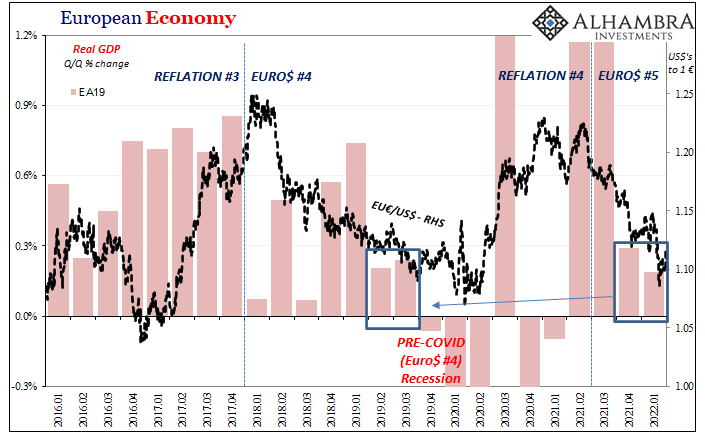

How else would we explain, for example, the euro’s absolute plunge since around May last year? Everything since would seem to agree with the conventional theory; the Fed has turned ultra-hawkish whereas the ECB has time and again very publicly stated it will resist the same temptation to chase CPIs.

As a result, expectations for much higher ST rates here versus there, therefore the euro’s plunge.

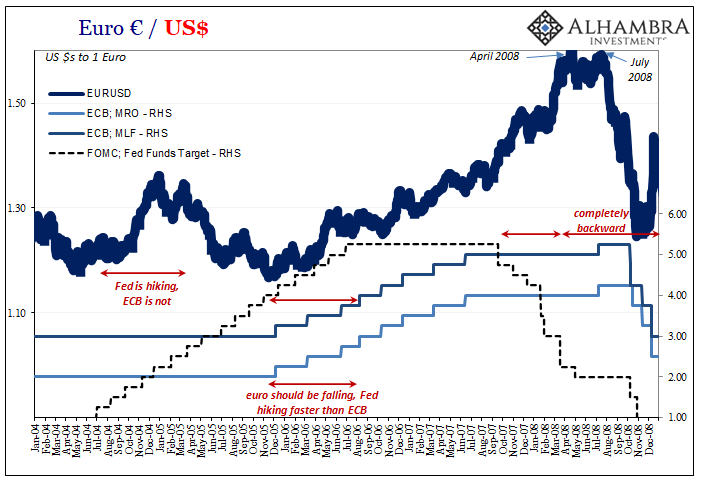

But why didn’t the same happen the last time both central banks went through this very same exercise?

Just like this time, Alan Greenspan’s Fed turned hawkish long before Trichet’s ECB would. The FOMC voted its initial rate hike in June 2004, while it would take Europe’s policymakers all the way until December 2005 to get started.

When all was said and done, Greenspan then Bernanke would raise fed funds well above the European policy corridor (the top half of it represented by the space between the MRO and MLF, where Eonia used to trade). Farther and faster, yet it was the euro not the dollar which rose in that period.

You could make the case (I wouldn’t) that the ECB was catching up after the Fed’s final hike and that accounts for a “stronger” euro particularly middle of 2006 onward.

Then once American officials began to cut rates in September 2007, the Europeans held steady and even, (in)famously, raised rates in July 2008. Euro went up.

But that doesn’t really make sense, either. While the first part could, up to April 2008, thereafter interest rate differentials grew more and more in the euro’s favor yet the euro not the dollar started to go down. By July 2008, just a week or so after Trichet’s embarrassing rate hike, the euro would absolutely crash.

That last part was very clear, at least, when the dollar was forced skyward by the arrival and eruption of Euro$ #1 going global; it had nothing whatsoever to do with interest rates on either side of the Atlantic or the currency equation.

So, we have to ask again; why is the euro down so much 2021-22?

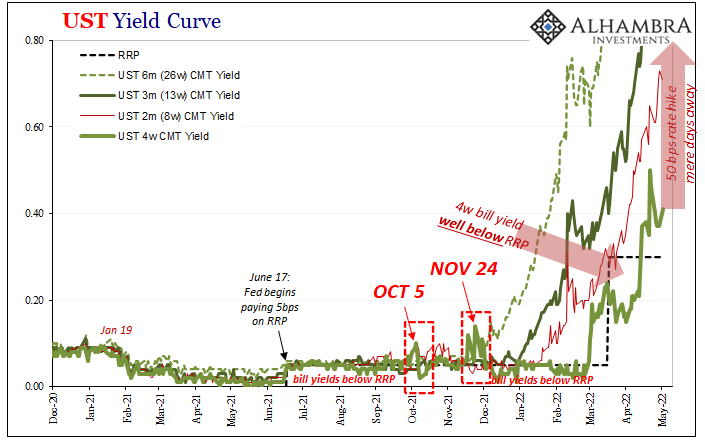

Rather than care much about the Fed vs. ECB, maybe a better question to ask is this: why is the 4-week Treasury bill sitting there on May 2 yielding only 41 bps? While that’s finally above the current RRP, you’ll note that beginning tomorrow the FOMC will meet and by Wednesday almost certainly announce that is has raised the RRP by 50 bps.

And even if policymakers do chicken out again, it will be a guaranteed twenty-five.

In other words, the RRP by Thursday has to be 55 bps minimum, though far more likely 80 bps. Yet, the 4-week bill (and the 8-week) isn’t anywhere close to either of those when by every investment return consideration it should already be above the latter.

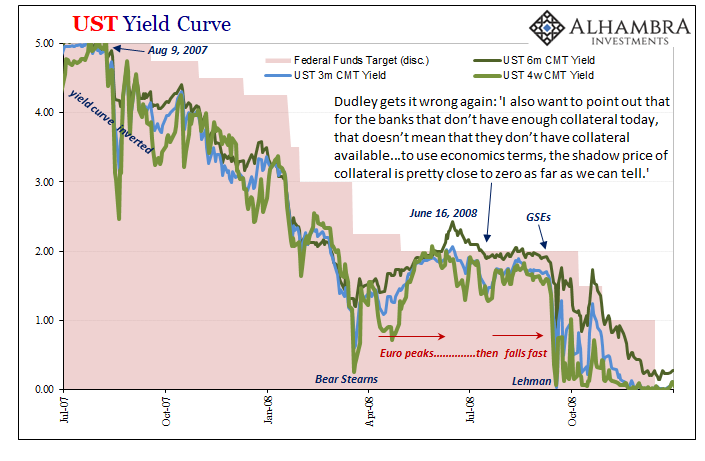

Wouldn’t you know it, too, that from late May 2008 all the way into that second phase of Euro$ #1, T-bill rates began to drop has they had leading up to Bear Stearns. These did not go unnoticed by policymakers; they were, obviously, totally unappreciated though not in the financial system itself.

Dudley’s claim and bill yields were in direct opposition (no surprise). Those exceptionally low rates would only have indicated “the shadow price of collateral” at the margins must’ve been exceptional high rather than zero as Dudley was alleging.

Though the system was far from normal, July 2008 wasn’t exactly full-throated crisis, either, and still yields indicated what they had. No, full-blown collapse would come not two months later when dealer aversion would again combine with, yes, another quarter-end bottleneck to absolutely devastate collateral chains, to simply implode the collateral multiplier leading to the mother-of-all-scrambles for collateral.

Or what’s called the first Global Financial Crisis.

From July 2008 onward, the system – and the dollar’s value – went full-blown Euro$ #1 which included an increasingly desperate scramble for collateral. All that even before Lehman.

It’s true the Fed is hiking rates more aggressively than the ECB in 2022, but not all rates are rising all that fast. Maybe it is those we should pay more attention to rather than policies, and not just as it relates to the euro’s falling value.

This doesn’t mean we are about to replay 2008, but it sure doesn’t indicate anything like the mainstream myth about the Fed, interest rate differentials, and what’s really goes on in the “dollar.”

Stay In Touch