By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Washington, D.C. January 20, 2012

The third week of every month is always a “feast” for the data hounds in the investment business, with a slew of coincident reports out from the Departments of Labor and Commerce on producer and consumer prices, housing starts and home sales, industrial production and capacity utilization, and employment claims. Additional monthly survey data on general business activity are released by the very robust research arm of the Philadelphia Fed and via the New York Fed’s Empire State Manufacturing Survey. While these high-frequency data are subject to monthly volatility, especially at the turn of the year when major business investment and employment decisions are executed, it is nonetheless a good opportunity to take stock of current conditions and prospects for 2012. This is so not least because of a famous anomaly in U.S. stock markets known as the “January Effect”, a phrase made famous after its description in a 1942 Journal of Business article by Sidney Wachtel. The late Mr. Wachtel, a legendary Washington D.C. investment banking fixture, had discerned that since 1925, common stocks had often outperformed the rest of the year and were often positive for the month, regardless of what happened the rest of the year. (If nothing else, one would be concerned if there were no lift in stock prices by mid-January.).

Data from the University of Chicago’s Center for Research in Security Prices dating back to the 1920s confirms this trend, and the related phenomenon that small-cap stocks usually outperform larger ones this month as well. And indeed, so far 2012 is true to historic form, with 12 of 14 trading days ending in the black (or green, if you watch CNBC), and the S&P 500 Index up sharply by 4.6%. Taking a longer view, U.S. stocks are up 95% since the March 2009 lows, and are now off only 16% from their all-time nominal highs (1565 on the S&P 500 Index, set on October 9, 2007). Given that we have recently predicted a modest ongoing expansion for 2012, what do these data tell us?

We comment here, in seriatim, on the major reports this week. The net of the analysis continues to show a steady albeit understated expansion, and low-grade inflation that, we strongly fear, may well be a harbinger of more to come in the years ahead, if not in 2012.

Producer Prices for December

The Producer Price Index for finished goods declined 0.1% in December, but was up over 12 months 4.8%; the 2010 increase was 3.8%. Food and energy prices declined -0.8% each, while all other finished (core) producer prices were up 0.3%. Intermediate goods were down -0.5%, while early-stage crude goods were down -1.1% last month.

Leading the decline in finished goods was gasoline, down -2.3%, and fresh and dry vegetables, down -11.1%, which led the first decline in food prices since May. Finished core prices were up by their largest amount in 5-months, with 30% of the increase due to a nearly 1% increase in light motor trucks. Meanwhile intermediate goods fell -0.5% in December (led by declines in organic chemicals and diesel fuel of -4% and -3.8%, respectively) after rising 0.2% in November, but they were up 6.1% in 2011 after rising 6.3% in 2010. In turn, crude early-stage materials were down -1.1% in December (led by foodstuffs and feedstuffs declines of -2.6%), but were up 6.4% last year after being up 16% in 2010.

Looking at the overall bundle, price increases moderated in the 4th quarter due to commodity price stalls in general, and the major categories of wholesale/retail trade, transport, and general service industries were quiescent. But the overall trend across the year is up, and core items such as construction machinery were up at their fastest pace in nearly 20 years in 2011. Given normal lags in supply-chain price reverberations, in spite of an elevated demand for money, higher prices (in the sense of above the average for the last decade) for consumers seem strongly possible, given activity levels across markets now. Hence we still see latent consumer price inflation in a likeliest scenario (given healthy year over year crude/early stage, intermediate, and finished goods price increases, respectively).

Consumer Prices for December

The CPI for all urban consumers — the “headline number,” is the second most important statistic in political economy after the unemployment rate. — was unchanged in December, repeating the no-gain in November. Year on year, the CPI jumped 3.0% (non-adjusted, and down from 3.4% in November). The energy index declined for the third month in a row (-1.3%, as did gasoline specifically), and offset slight increases in the indexes for food (0.2%) and the core number (which is all items less food and energy, and rose 0.1%; core prices are up 2.2% versus last year, above Fed targets). As in both October and November, the household energy index declined; the food index rose slightly in November, along with shelter, recreation, medical care, and tobacco. Meanwhile prices for used cars and trucks, new vehicles, and apparel all declined.

Sadly, real average hourly earnings, which are the cash earnings of all employees, adjusted for inflation – rose 0.2% in December, but are down 0.9% in the past year. However because of a 2.3% increase in hours worked, total cash compensation grew. Real weekly earnings are down 0.3% in the past year.

Looking out over the last twelve months, energy and food prices are indeed driving CPI advances: energy prices across all categories are up 6.6%, while fuel oil alone is 18% higher than a year ago. Food prices are up 4.7%, with home-based food 6.0%, while other important categories include new/used vehicles (3.5%), housing (1.9%), apparel (+4.6%) and medical care services (+3.6%). In spite of a flat 4th quarter, the overall report for 2011 comes in with elevated consumer prices against Federal Reserve targets, and the high likelihood is for similar inflation numbers in 2012. Again, our worry is in the years ahead.

Weekly Jobless Claims

The Labor Department’s Employment and Training Agency announced that weekly new claims for unemployment insurance declined by 50,000 (down -15.2%) during the week ending January 13, to 352,000, from the previous week’s revised figure of 402,000. This was the lowest showing in nearly four years, and the four-week moving average of 379,000 was a decrease of 3,500 from the previous week. This was also a big improvement from the year ago number of 415,000.

Key state-by-state results include the following:

The highest insured unemployment rates in the week ending December 31 were in Alaska (6.9), Connecticut (6.6), Oregon (5.0), Wisconsin (4.9), Pennsylvania (4.7), Idaho (4.5), Rhode Island (4.5), Montana (4.3), New Jersey (4.2), Arkansas (4.0), Illinois (4.0), and Washington (4.0).

The largest increases in initial claims for the week ending January 7 were in New York (+29,389), California (+22,168), Texas (+13,946), North Carolina (+7,865), and Georgia (+7,225) while the largest decreases were in Wisconsin (-7,657), Michigan (-5,208), Iowa (-4,675), New Jersey (-4,667), and Kentucky (-3,577).

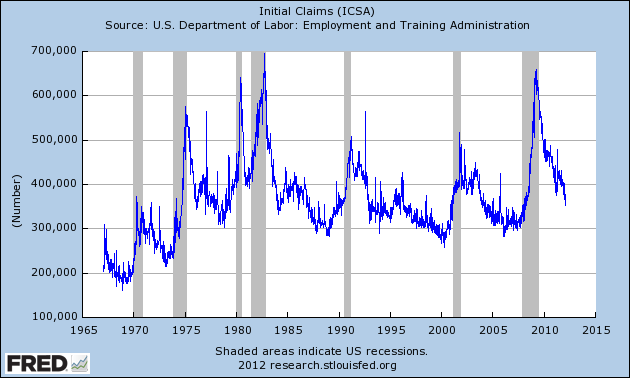

Below is the Fed’s data in graphic form depicting newly unemployed who are eligible for insurance payments, going back 44 years. We follow this chart closely because for the economy to be truly healed from the late recession, the weekly claims number must consistently average no more than 350,000, where it is now, and need to dip below this at times. Indeed the story of the U.S. economy in 2012 will usefully be told in looking at this chart one year from now:

Chart I. Weekly Initial Claims for Unemployment Insurance (1967-Present)

While the “jury is still out” on this recovery, this chart alone will tell the tale in the time ahead as to its durability.

Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization in December

Industrial production was up 0.4% in December, with upward revisions to the 4th quarter as a whole, and came in at 2.9% in the past year. Basic manufacturing was up 0.9% last month, while auto production especially surged: it was up 0.6% and 10.3% year-on-year (manufacturing ex-autos was up 3.3% in the year just passed; sales of autos, meanwhile, surged 8.4%). High-tech capital goods were also up slightly for the month and year, feeding strong demand in the IT sector in the U.S. Meanwhile, capacity utilization increased to 78.1% in December from 77.8% in November. Manufacturing capacity use rose as well, to 75.9%.

Additionally, both the Philadelphia and New York Feds’ reports showed improvements in manufacturing. The Empire State Index (which tracks manufacturing in the state of New York), increased to +13.5 in January from +8.2 in December (this index was negative earlier in the year). And the report from the Philadelphia region was solid:

The survey’s broadest measure of manufacturing conditions, the diffusion index of current activity, edged up slightly from a revised reading of 6.8 in December to 7.3 in January. The demand for manufactured goods showed continued growth this month: The new orders index remained positive for the fourth consecutive month…. the shipments index also remained positive.

Firms’ responses continue to suggest that labor market conditions are improving. The current employment index has now been positive for five consecutive months but was virtually unchanged from last month’s reading. The percentage of firms reporting an increase in employment (21 percent) was higher than the percentage reporting a decline (10 percent). Firms reporting a longer workweek (23 percent) only narrowly outnumbered those reporting a shorter one (18 percent).

Housing Update

The U.S. housing sector is showing signs of life. Most prominently, the sentiment index from the National Association of Home Builders, which measures their members’ confidence, increased to 25 in January, the highest reading since 2007 and well above expectations (this index was at 14 just three months ago). And while housing starts were down (-4.1%) in December to 657,000 units (annualized), starts are way up from a year ago (+24.9%) — and within this figure, the breakdown is skewed toward rental properties: multi-family starts are up 78.1% year-on-year, while single-family starts are up 11.6% (and permits for multi-unit homes are up 27.0% year-on-year so the strength will continue into 2012).

Longer term, the day of the turnaround for housing draws nearer. The U.S. population is growing at 1.1% per year for people over age 25, and if half of them demand housing every year, along with scrappage, the demand should already be at least at a million units. Given the excess inventory burn-off that is ongoing, starts should be double where they are now in the next three years or so, and back to the steady state in the run up to the boom (1.2-1.5 mm units annually). This leads us to believe the low point for housing construction has been passed, but we must issue this cautionary note: former Fed director of research and right-hand man to Chairman Bernanke, Vincent Reinhart (now Chief Economist at Morgan Stanley), has recently stated the Fed will engender a QE3 to the tune of $750 billion in new mortgage-backed purchases, beginning as early as March when private demand is sapped. We will be writing in pre-emptive protest on this in the weeks ahead: conditions do not warrant this in our view and indeed, it merely exacerbates an exit problem for the Fed with respect to excess reserves, as well as engenders more inflation, asset bubbles, and malinvestment (it will, however, put a floor on stock prices this year as and when it happens).

Conclusion

We never tire of repeating that our admiration for American entrepreneurs, workers, and business leaders is boundless. While the Eurozone is imploding, Japan continues to writhe in economic torpor, China slows, and instability abounds in the Middle East, and in spite of headwinds caused by — there is no other way to say this — the retrograde policies of a clueless Beltway political class (including the Fed, in our view), the U.S. economy hums along. In addition to the data above, recent reports showed retail sales up 6.5% year-over-year (December), durable goods orders up 9.1% year-over-year (November), and most important of all, approximately 1.9 million jobs were created in 2011, as the unemployment rate fell to 8.5%.

At the least, all this adds up to continuing growth across 2012, absent a melt-down in Europe. What can this mean for U.S. equities this year? We are on record as predicting gains in GDP and the stock market in 2012, and we stand by this, although it is true that Europe remains an unknown, and China, the rest of Asia, and the Middle East may all contain some surprises to the downside. We do think, though, that in a year where corporate profits rose should rise 8-10% to new record highs, following a a year where a 15% profits-surge to a new record was not accompanied by a move in the market, that equities should rally. Indeed, this seems further assured by an accommodative Federal Reserve well into 2013.

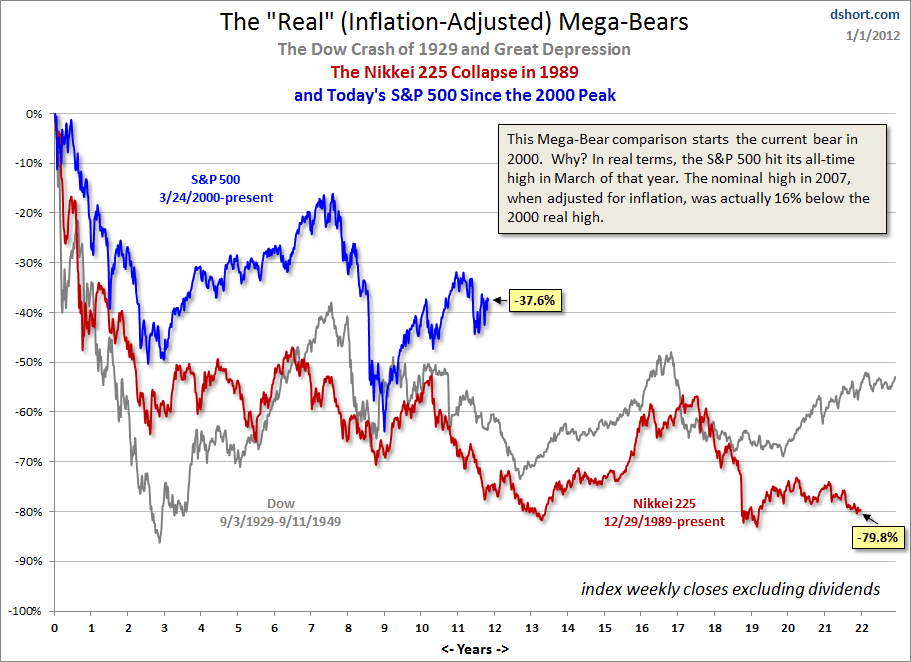

Longer term, if policy in the U.S. reverts to a pro-growth stance, there is considerable upside in U.S. markets. Our friend Doug Short published the attached chart earlier this month at Seeking Alpha, and it shows the market’s progression for two decades after the start of downturns in both the U.S. (1929 and 2000) and Japan (1989):

Chart II. Long Term Bear Markets in the U.S. and Japan

. Courtesy of Doug Short (2012).

Courtesy of Doug Short (2012).

This shows that the market is still 38% below its 2000 high in real terms, and has plenty of running room when policies are more propitious in terms of inducement to invest. But the chart also shows — in a glaring warning — the ongoing tragedy in Japan, which the U.S. is not at all guaranteed to avoid.

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Appendix on Analytical Approach on Producer Prices.

As a gauge for future inflation — and hints at latent consumer price trends of course — the Producer Price Index (PPI) is, for us, preferred as a tool to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Indeed, this is one of the most important metrics we survey over time. This is because the PPI sectors are interest-rate sensitive and will always be responsive to increases in the quantity of money and credit. This is less true of consumer goods; modern competition can hold consumer goods prices down even in the face of an inflation in the supply of money and credit, which is then manifested in distortive international dollar flows, or flows of new credit money into financial assets. But an increase in the money supply that artificially lowers rates will axiomatically lead to dollar flows into early-stage goods, causing the PPI to rise.

Indeed, in an unhampered market economy, the PPI should slowly decline over time, as per Moore’s Law being in force for computer chips. Technology may come in non-linear waves, but will put pressure on prices over time. Thus a secularly rising PPI episode usually means inflation, a lack of technological or productivity improvement, or both. A flat or slightly declining PPI would mean sound money and technological gains are being made through investment.

Methodology

Our methodology for examining producer prices is to always look at total (group-wide) price changes, and then those for core goods (all except food and energy, which the U.S. government statisticians have singled out for their volatility), and non-core items (food and energy). And, we review finished producer goods, intermediate (in-process) producer goods, and crude (early-stage) goods (these are the three stage-of-process prices collected by the U.S. government that collectively make up producer goods). On core versus non-core items, our view is this is detrimental to the analytical process because the Fed’s economic staff-members attempt to absolve themselves from inflation in food or energy per se, when indeed increases in the supply of money and credit can be channeled into these immediate consumables as per anywhere else. But now the entire U.S. government apparatus has picked up on the distinction, and it is important to follow this framework as an investor because these data do move asset markets.

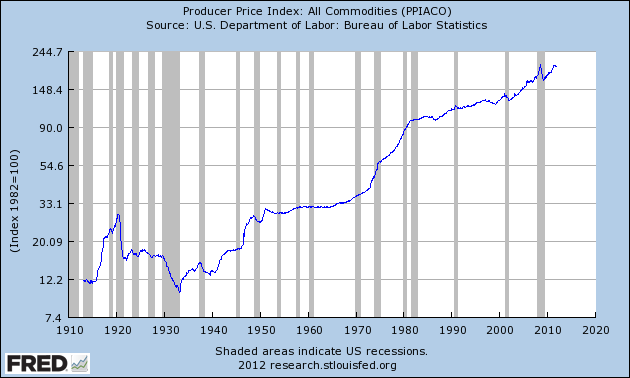

The chart below shows the century-long time series of producer prices going back to the Fed’s inception in 1913, and it is illustrative because it shows there is, if anything, a near-zero correlation between the PPI and economic growth:

Chart III. Producer Price Index (All Goods), 1913-Present, Log Scale (1982=100)

We prefer a logarithmic scale for data such as these because it shows equiproportional changes in movement of parameters across time. In the case above, the intervals increase 65% in each case. What this graph tells us is that long periods of flatness in this curve are coincident with strong economic growth because they incite strong profits. Thus, the 1920s, the period from 1950-70, and the 1982-2000 period are marked by little rise in the graph, and these were the best periods for growth in the last century. Conversely we see a big arc in producer prices in the 1970s, and again though less starkly, interestingly, after 2002. Relative profit levels are not as strong in such periods, but the obverse of this not desirable, either: sharply declining producer prices are usually indicative of a downturn.

Producer prices are correlated with future consumer prices, though not perfectly, and they can diverge for long periods. Why might producer prices rise faster than consumer prices? In the age of the Internet and ubiquitous competition, fueled by more open trade, competition in product markets almost guarantees this. Consumers seemingly have endless choices and thus will not tolerate price increases foisted upon them easily, but capital good industries, always very interest-rate sensitive, have to absorb price increases that come with more money and credit in the economy chasing those low rates (in the 1970s inflation, however, trade was not as competitive, and union bargaining was able to force up wages repeatedly — this was bound to affect consumer prices; the demand for dollars has skyrocketed in recent years as well, allowing the U.S. to “export inflation” more than in the past — and, currently, the demand-for-money-to-hold is high as well, as now U.S. citizens are adding to cash balances due to fear). But for our purposes, analytically, a rising PPI is a warning siren about profits and a threat to consumer prices down the road, whereas the 1950-70 or 1983-2000 periods above are conducive to strong growth.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alhambra Partners Disclaimer: The information contained in this note comes directly from U.S. government sources (such as the Federal Reserve Board, U.S. Commerce Department, or U.S. Census Bureau), or from financial news websites or the print press (such as Bloomberg, Reuters, or the Wall Street Journal). The data contained herein are generally believed to be accurate, but Alhambra makes no implied or express warranties in this regard. Our aim with this commentary is to provide insights that could allow for the formation of investment strategies by individuals and firms, but forward-looking assertions again come with no express or implied warranties, and the purchase of investment securities comes with high risk. The opinions expressed here are those of John L. Chapman, and do not necessarily reflect those of colleagues at Alhambra Investment Partners, LLC or any of its affiliates.

Stay In Touch