Thinking Things Over April 15, 2012

Volume II, Number 15: Are Stocks Fairly Priced? Efficient Markets and Inefficient Politics

By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Canton, Ohio.

Investors are living through an era of extraordinary uncertainty, as evinced by the incredibly wide range of professional opinion available at the moment from amongst the economic and financial commentariat. In the following essay we offer a rationale for belief that the likeliest path in the years ahead is, unfortunately, Japan-like torpor, but a plausible story for a path to a sunnier future is also outlined.

What Is the “Correct” Value for the S&P 500 Index?

On October 28, 1980, Ronald Reagan met President Jimmy Carter in Cleveland, Ohio, in that fall’s only debate between the two Presidential contenders. Coming just a week before the election itself, with polling still tight in most states and a third party candidate with potential clout (Congressman John Anderson of Illinois, who did in the event end up with nearly six million votes and tipped some states to Mr. Reagan), there was high drama attached to the evening, especially given the sorry state of the U.S. economy at the time. Mr. Reagan won the debate and the election that night with a storied line in Presidential campaign history (“There you go again…..”), but his most important line of attack that evening spoke to the millions of workers, employers, and investors who had been hammered by the “stagflation” of the 1970s. Quite simply — and devastatingly — Mr. Reagan asked American voters: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” It was a fair query in a time of 21% interest rates, 13% inflation, nearly 8% unemployment, and corporate investment and real wage growth that had reached post-war lows.

The stock market in 1980 was in a moribund state, then in the 15th year of the long 1966-82 swoon, when U.S. equities lost 70% of their real value. After peaking in real terms in 1968 when crossing 108, the S&P 500 Index began 1980 at 105.76, and finished the year up 28%, north of 135 on the Index (or, up about 14% in real terms thanks to the 13.6% inflation rate in 1980 in the U.S.). There was no valid reason for a 14% real gain in U.S. equities that year: the economy was in the first leg of a “double-dip” recession, corporate profits were stagnant, investment had been choked off by high interest rates and high and variable inflation, and the trade-weighted value of the U.S. dollar continued its decade long, post-1971 slump. Further, tensions were rising abroad, with oil threats due to a revanchist Iran, which had committed an act of war in transgressing the U.S. Embassy in Tehran; the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and its Navy installed at Cam Ranh Bay, while the Chinese Army menaced the Vietnamese border; and a tenuous Mideast “peace process” that was soon to blow up with the brutal murder of Egypt’s Anwar el-Sadat in 1981, threatening another Arab/Israeli war.

What then could account for the strong showing for S&P 500 stocks that year? The only variable that offered investors upside at the time was the election of Mr. Reagan, and some level of prospective change in the macroeconomic policies pursued by President Carter. And indeed, history bore this out, for investors who bought stocks in U.S. companies in 1980: after the Economic Recovery and Tax Act passed in August, 1981 (and its promised deep cuts in marginal tax rates beginning in January, 1983), combined with Mr. Reagan’s active and vocal support for the Volcker Fed’s strong dollar policy and the Administration’s commitment to curtail regulatory and antitrust roadblocks, the end of recession in 1982 ushered in an unparalleled boom in U.S. equities into the new millenium. After the fact, we can see that a time of darkness for investors, when gloom was pervasive, was instead, as Warren Buffett later called it, the most extraordinary buying opportunity in generations.

The lesson from that period is that policies out of Washington that are conducive to promoting a stronger U.S. dollar and better climate for investment (and thus, prospect for U.S. corporate profits) will surely lead to rising equity prices on a sustained basis. Could this be at least somewhat true as well, of the current moment in the United States? Out of such a deep recession, with significant unused capacity and idled resources, fallen wage levels, and ongoing deleveraging and recapitalization of both households and businesses, could we be on the cusp of a long boom once again?

On this, opinions are far and away divided. Professor Jeremy Siegel of the Wharton School of Business is extraordinarily bullish: he thinks stocks are at their lowest levels, in a relative sense, in six decades. Says Mr. Siegel:

Stocks are fairly cheap on an absolute basis. They’re extraordinarily so on a relative basis, about the most relative cheapness I’ve seen stocks probably since the 1950s. In 2000, we were starting at a 30 price-earnings ratio. That was the most that the stock market has ever been in the world. It’s not surprising the next decade is going to be bad when you start at a 30. When you start at a 13 price-earnings ratio….the future is much, much brighter. We’ve never had bad stock returns over the next three, five, or ten years when you start with a 13 P/E ratio, and that’s a world of difference.

Mr. Siegel has gone further, and is on record in just the last week as saying there is a 75% chance the Dow Jones Industrial Average will hit 15,000 by the end of 2013, and a 50% chance it will hit 17,000 (representing 16.7% and 32.3% increases, respectively, from the current valuation level, if these levels were attained), thanks to price-earnings ratios being below their historic means (actually, the Dow Jones P/E is currently 14.4, while the S&P 500’s is at 16.3) alongside a very healthy U.S. corporate sector grown leaner and more efficient in the late recession, and thus able to sustain current profit levels.

Mr. Siegel’s thesis is even more plausible as a relatively short-term call when considering U.S. monetary policy (which, strangely, the Wharton professor and long-time bull routinely ignores): prospects are lengthening for some sort of “QE3”, or continued ease well into the middle of this decade, absent any inflationary bursts in the U.S. And, while never good over a longer period for asset prices due to the capital malinvestment and over-leveraging spawned by excessive monetary and credit expansion, in the short run, Fed easing moves have routinely led to a positive “bump” in financial markets since the 1970s. Thus, Dow 15,000, at least, certainly seems plausible (and an equivalent move up of 16.7% for the S&P 500 Index would take it to 1618 by the end of 2013, implying a P/E little changed from today if consensus earnings expectations are met).

But there are of course major warning signs on the horizon, too, and Gary Shilling well represented bearish sentiment in an interview on Bloomberg TV on April 11, when he predicted a sharp drop in U.S. corporate earnings this year and the likelihood of a U.S. recession, with stocks in the S&P 500 Index retrenching to 800:

The analysts have been cranking their numbers down. They started off north of $110, then $105. They are now at $102 [for S&P 500 earnings in 2012]. They are moving in my direction. I think that is true because you have foreign earnings that don’t look good because of recession unfolding in Europe, a stronger dollar, so there are [currency] translation losses. A hard landing in China. In the U.S., we could see a moderate recession led by consumer retrenchment. I think that my earnings estimate [$80] is not unreasonable…it’s a quartet [of investing strategy, now]; [I am] long treasuries, short stocks, short commodities, and long the dollar. The story is that there is nothing else except consumers that can really hype the U.S. economy. Consumers have been on a mini spending spree…[but] incomes have simply not kept up. Of course, the real key behind that is employment. It looked earlier like jobs were picking up and that was going to provide the income and people would spend it, so on, so forth. But the employment report that we got last week throws cold water on that. Consumers have a lot of reasons to save as opposed to spend. They need to rebuild their assets, save for retirement. A lot of reasons suggest that they should be saving to work down debt as opposed to going the other way, which they have done in recent months. So if consumers retrench, there is not really anything else in the U.S. economy that can hold things up.

This is a thoroughly Keynesian analysis, and one long favored by Mr. Shilling: for him as for Keynes, consumer spending drives the economy, not investment; a strong dollar is bad for stocks because it is bad for U.S. corporate earnings of multinationals; saving is antithetical to a vibrant and growing economy because it short-circuits the stream of spending and thus aggregate demand and corporate profits. All of this is incorrect in our view for anything other than the short run (which, after all, was Keynes’ focal point), but this is beyond the scope of the present discussion. For indeed, Mr. Shilling’s “mode” of thinking is fairly representative of money managers and analysts on Wall Street. Current bears such as Nouriel Roubini or PIMCO’s Bill Gross would not at all disagree with Shilling’s general line of thinking, if not his magnitudes.

Mr. Shilling goes on to add that the U.S. economy is the “best of the bad lot.” China, Europe, and Japan all represent near-term recession for him, but capital flight from those markets will not, in his view, move toward U.S. equities. Instead, he is looking at the U.S. Treasury’s long bond, and sees the yield heading to 2.50% by next year (from 3.12% currently), while the 10-year is headed to 1.50% from 2.04% at the moment. Who is right: a “bear” calling for 800 on the S&P 500 Index, or a “bull” calling for 1600?

Markets are “Efficient” — in the Long Run

Space does not permit us here to review the high-frequency economic data out in weekly droves about the U.S. economy, but as a general matter, beyond China, the Eurozone (and now Spain, especially), Japan, and the unsettled Middle East, indices for such items as employment and job growth, consumer spending, corporate profit growth and target achievement, housing and consumer durables, factory orders and utilization, and even some of the sentiment indicators, are all off their recent highs, or up-trends. There are cautionary winds abounding at the moment (countervailed by continued extraordinary ease in monetary policy). We are led in such a moment to take comfort in the University of Chicago’s Eugene Fama, the father of modern finance, whose pioneering work on asset prices furthered the CAPM and APT models, along with notions about the relative degree of pricing “efficiency” in asset markets, moment to moment (and Professor Fama, in our view, should have won the Nobel Prize by now, a crime we hope and anticipate will be rectified in the next few years).

To actualize Fama’s core teaching, we cannot know if asset prices — in this case, U.S. equities — are priced “efficiently”, that is to say, “accurately” in an “objective” sense, at the moment. But we can have strong confidence that they will move toward “accuracy” in a year, in five years, and in ten years even more so, to the degree they are mis-priced today. And in this regard, use of the Shiller P/E ratio, which uses a previous ten-year average of earnings as opposed to 12-months trailing only (or, 12-months forward, in the case of forward estimates), smooths out the past by eliminating outlier periods to a degree. Combined with fundamental analysis of U.S. corporate assets moving forward in tandem with likely U.S. monetary policy, the Shiller P/E gives us some measure of confidence in our positioning for near term direction in markets.

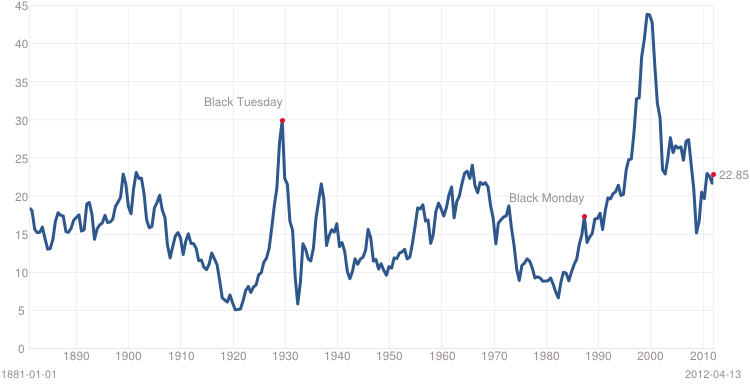

And here, the Shiller historical chart is interesting as well as revealing:

Chart I. The “Shiller P/E” Ratio for the S&P 500, Extrapolated Historically, 1881-Present

In fact, the long-term mean of the Shiller P/E ratio is 16.42; it is nearly 23 today. That is one cause for concern, if one believes, as does Professor Fama, that markets are more informationally-efficient today than they have ever been in the past (the dot-com bubble and Fannie/Freddie/Fed-induced frauds notwithstanding). To see the rise in equities that Mr. Siegel does, S&P earnings would have to climb to $110 per share next year, and have sentiment in the U.S. raise the P/E ratio to nearly 25, to hit 1618 on the S&P 500 Index. Fundamental analysis of U.S. corporate earnings prospects would seem to negate this as a possibility, but equally so does it for a drop of the magnitude forecast by Mr. Shilling (that is, for the S&P 500 Index to fall to 800, a drop in earnings to Shilling’s estimate of $80 would mean that sentiment alone would pound down the Shiller P/E to 14 a year from now, say, from its current level of almost 23 today).

Of course, Mr. Shilling’s prognostication is possible: war in the Middle East, a blow-up in China, confiscation of all earned income above $500,000 in Eurozone countries (such as is now being promulgated in France by the far-Left candidate, Jean-Luc Melenchon), and, we cannot forget, anti-growth policies in the United States (such as huge tax increases beginning in 2013), could all combine to “pile-drive” equities down to 800. But our scenario analysis utilizing the Shiller P/E tool, precisely because of its effectiveness in smoothing out earnings trends — and thus, in a way, pointing us toward Fama’s long run “efficiency” in asset prices — combined with fundamentals extant in the U.S. economy with respect to corporate profit growth and continued monetary ease in the U.S., all lead us to believe we are in a “long-term trading range” of 1080-1550. The trick for investors in the time ahead will be to seek hyper-efficient, global diversification (of asset classes as well as geographies) along with being alert to “special situations”, cases where, say, an individual stock is grossly undervalued. To go on record specifically, we are cautious at the moment, support the use of cash as a de facto asset class itself in this period of remarkable uncertainty, but do anticipate 2012 being a year of growth for U.S. equities (it is more than possible though that the S&P 500 Index ends 2012 close to where it is right now, albeit with some volatility in the months ahead — this would represent a gain of roughly 10% on the year, which is where we are year-to-date).

What Would Lead to a Brighter Future?

The decade of the 1970s — and especially 1974-82, when real economic growth in the U.S. averaged 2%, far below the historical norm of 3.4% in the United States– was a time of stagnation and lousy performance for U.S. equity markets. More than anything, what broke the torpor of that time was a new policy regime in Washington, D.C., one that was long-term oriented. It was a policy mix designed to be friendly toward capital investment, savings, entrepreneurship, and income generation, to all of which a happy resulting concomitant was the deployment of radical new technologies that spurred productivity in the ensuing 25 years. There is no reason the current torpor cannot also be eradicated, through policies that are once again capital-friendly and pro-growth, or pro-prosperity. The Shiller P/E graph shown above looks “ugly” during the 1970s and early-80s, and then looks much better after 1982. How can a similar turnaround be effected once again?

As has been the case since the American Civil War, the key for the global economy as well as here is a change in economic policy in the United States. For indeed, as we never tire of pointing out, as goes the United States, so will go the rest of the world. A return to a sound dollar policy is imperative, and it means the slow but systematic shrinking of the Fed’s balance sheet and — ideally — explicit commodity price targeting. Better fiscal policy in the U.S., best portrayed in spending roll-backs and pro-growth tax cuts (such as, in a perfect world for example, the elimination of the tax on corporate profits), would mitigate rising interest rates in the U.S. (and around the globe), and open the door to productive and badly-needed investment. And, a reduction in the increasingly out-of-control (and job- and investment-killing) cost burdens entailed in the interventionist oversight framework in the U.S. would complete the monetary-fiscal-regulatory trifecta that is now so needed, and go a long way toward beginning a new and exciting era in world history. For the good news is, the world stands on the cusp of technology-driven revolutions in dozens of industries, from energy to health care to manufacturing to information-based and knowledge-intensive sectors (e.g., education, financial services, production control), but at the moment, the policy framework to exploit these radical new innovations is missing.

Bluntly, the denizens of the developed countries around the world — that is, the countries that drive global growth — now face a choice: continued slow, sclerotic torpor in the form of sub-2% annual growth for the advanced economies, thanks to an ever larger footprint of government in their respective societies, or a return to strong global growth in the 4-5% range (which implies the U.S. returning to its historic average north of 3%). The former implies a long repeat of the 1966-82 market stagnation and real decline (or, we must sadly say, the 1998-2012 market volatility that led to no real growth in equity value, end-to-end), whereas the latter would lead again to real gains in equities — and in recapitalization of the entire U.S. (and global) economy. With that, of course, comes rising living standards everywhere. On these weighty matters the world’s voters begin making their fateful decision next month, with elections in Europe, and what may well be an historic inflection point on November 6, in the United States.

Epilogue

We never tire of showing the chart of Japanese equities after their peak in 1989, shown again below. We cannot think of a better warning to U.S. policymakers about the consequences of their actions moving forward. Twenty years ago Japan had a debt-to-GDP ratio of 35%; today it approaches 200%, after multiple and massive rounds of Keynesian “stimulus”. Japan has always been a high-tax welfare state, the burdens of which have now “come home to roost.” The Nikkei 225 chart shown below is a graphic portrayal of both tragedy and political class betrayal, but it is a history that every American voter would do well to apprehend.

Chart II. The Nikkei 225 Index for Japanese Equities, 1985-Present

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch