Thinking Things Over May 13, 2012

Volume II, Number 19: Fundamental Monetary Reform Is Coming…(Part One)

By John L. Chapman, Ph.D. Washington, D.C.

The monetary system is to the economy what circulating blood is to the body: the former enables the latter to function. If the former is plagued with a virus, the latter will degrade and ultimately break down if the “disease” is not vitiated. Some people in Washington understand this, and are trying to effect necessary change before it is too late. Investors need to understand these are not mere parlor games anymore.

Big-cap U.S. equities were down 1.7% last week, as nerves about even the blue-chips were frayed by the $2 billion hit to J.P. Morgan’s balance sheet via trading losses. In the wake of this unsettling news that also took more than 9% out of JPM‘s equity value in one swoop, no less than the well-connected star of bond market investing, PIMCO’s Bill Gross, all but guaranteed a new round of quantitive easing later this year. This, even though Mr. Gross readily admitted in the same discussion that this may not be a wise thing in the long run.

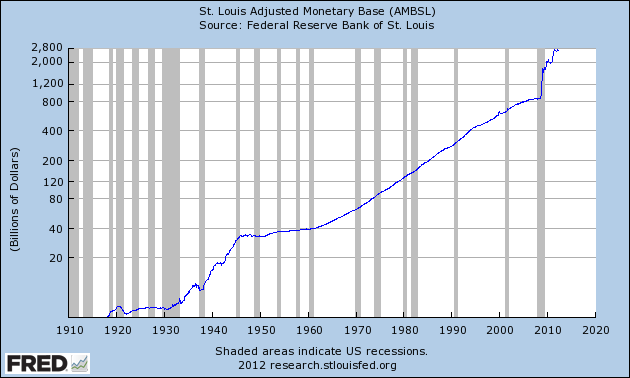

Mr. Gross may well be correct in his thinking, and indeed, the bond king is not shy about talking his book: PIMCO has invested heavily in mortgage-backed securities of late, holdings that would surely rise in the event of a “QE3.” In the short run, we confess to not understanding the thinking at the Fed: the Producer Price Index (PPI) declined 0.2% in April, versus the consensus expectation of no change. But producer prices are up 1.9% versus a year ago (the consumer price index [CPI] is announced Tuesday, but has lately been running at a +2.7% annual rate), and core intermediate producer goods prices (that feed final PPI) are accelerating at a +7.5% annual rate since the year’s beginning. We think inflation is headed higher this year in any case, and therefore it can only mean a QE3, if it happens, is intended to prop up bank balance sheets. Given this, rumors of more easing make sense: the J.P. Morgan loss that rattled investors around the world may be one more stake in the ground along the way toward another Bernanke-triggered QE round. After all, if JP Morgan can seemingly make such big errors in trading bets, the Fed Chairman may well reason, what of the majority in the banking sector who are less well-capitalized? And, the broader measures of the money supply that hold Mr. Bernanke’s attention, M2 and MZM, are both growing near their long run trends (see M2 here), and not inordinately:

Chart I. M2 Growth, 1980-Present, Log Scale

Indeed, while approaching a mind-boggling $10 trillion level, M2 has grown at less than 6% per annum since the end of the recession, not far above its historic growth rate. And, given the plunge in M2 velocity to lower levels than have ever been recorded since the Fed began tracking this data series in 1958, Mr. Bernanke clearly believes it is a better than even money bet that another round of QE will do little to consumer prices in the United States.

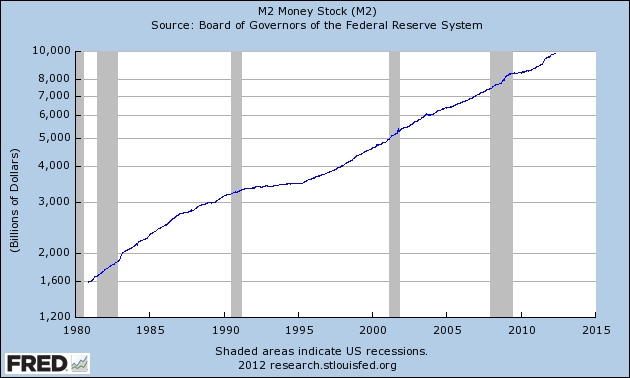

In the short run, he may well be right, and a QE3 would likely provide some sort of temporary lift (and in our view, no more than that) to asset prices in the U.S. and, by extension, perhaps to Eurozone and other major bourses around the world. But at what cost? Monetary policy, reform, and money’s effect on the economy are increasingly in the news lately (e.g., Herman Cain advocates a return to the classical gold standard in the May 14 Wall Street Journal), and were in a major way on Capitol Hill this past week. Congressman Ron Paul (R.-TX), the Chair of the House Financial Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Domestic Monetary Policy and Technology, held a hearing to examine the Fed’s statutory dual mandate (to promote price stability and maximal employment and growth), and broached long run reform as well. Specifically, the panel looked at policy options in the face of a Fed balance sheet that has grown enormously in the last four years, per this graph of the adjusted monetary base:

Chart II. Federal Reserve’s Monetary Base, 1918-Present (Log Scale)

This graph is illustrative because it provides historical context to show just how far out of the ordinary recent Fed policy has been: the monetary base had been growing at a fairly steady pace since 1960 (about 6.5% per annum), right up into the spring of 2008. In the last four years, however, the base exploded at a 34% annual pace, from $850 billion to $2.646 trillion last week (this, after a 3.9% drop from the all-time high of $2.753 trillion at the end of February). Clearly, the Fed is operating in uncharted waters now, and it is hard to see how this can end well, based on prior histories of rapid base money creation around the world.

This graph is illustrative because it provides historical context to show just how far out of the ordinary recent Fed policy has been: the monetary base had been growing at a fairly steady pace since 1960 (about 6.5% per annum), right up into the spring of 2008. In the last four years, however, the base exploded at a 34% annual pace, from $850 billion to $2.646 trillion last week (this, after a 3.9% drop from the all-time high of $2.753 trillion at the end of February). Clearly, the Fed is operating in uncharted waters now, and it is hard to see how this can end well, based on prior histories of rapid base money creation around the world.

Congressman Paul’s subcommittee hearing addressed this circumstance, and was evenly balanced: defending the Fed’s recent actions and dual mandate were former Fed Vice Chair Alice Rivlin, now back at the Brookings Institution after her time on the Bowles-Simpson Commission, and University of Texas economist James K. (“Jamie”) Galbraith, the son of John Kenneth Galbraith and a former congressional staffer who helped draft the Humphrey-Hawkins dual-mandate legislation back in 1978. Stanford University economist John Taylor, author of the famed “Taylor Rule” of monetary policy, was on the panel occupying a “middle ground”: he advocates a more focused and rules-bound Fed concentrating on price stability only, and asserts that the emphasis on employment and output growth can often be counterproductive, since stop-go monetary policy has historically been destabilizing and a cause of boom-bust cycles.

A harsher assessment of Fed performance was offered by the University of Missouri’s Peter Klein, and Grove City College economist Jeff Herbener, both of whom advocate the Fed’s abolition. Messrs. Klein and Herbener would replace the Fed-centered commercial banking system with an industry in which financial firms issued their own notes, competitively, backed by a commodity that would likely be gold. Their arguments are worth reviewing as a harbinger of what is in store, and we do so next week in this space.

No Good Options Now?

The size of the Fed’s balance sheet was remarked upon by all five economists, all of whom agreed it had grown large enough for now. Professor Galbraith and Dr. Rivlin are, however, like Chairman Bernanke himself not worried that it will be destabilizing or inflationary, while Messrs. Herbener, Klein, and Taylor are. Clearly, if Mr. Bernanke fears weakness in the U.S. banking system — or the potential need for dollars in an imploding Eurozone — he is loath to shrink the balance sheet much now.

But even Dr. Rivlin is worried about the gargantuan size of Fed holdings and wants to see a paring back. There are of course three tools on hand for the Fed to shrink the banking system’s level of free reserves when it decide to move, and in changing contexts that might materialize in the near future, all are worrisome for the three doubting subcommittee witnesses (Klein, Herbener, and Taylor):

(1) Sell Assets to Pare Down the Balance Sheet. The Fed could very directly shrink its balance sheet by selling assets out of its mortgage-backed and Treasury portfolios, reversing its heavy purchasing on the open market in the last few years during multiple rounds of quantitative easing. But this will of course cause interest rates to jump. While a negligible problem initially given today’s low interest rates across the yield curve, higher interest rates will of course hurt those real estate and financial firms (banks and other lenders) the QE policies were most designed to help. Higher rates will also dampen any ongoing recovery, such as it is, and will likely herald a new recession in the United States (as rising rates usually do). But the longer the Fed abstains from doing this, the likelier that inflation will rise, also stunting growth and investment, not to mention pounding consumers and creditors who are already hard-pressed. Professor Taylor in particular fears a new episode of stagflation is likely in the offing as spending velocity picks up, which he foresees.

(2) Raise bank reserve requirements. The Fed could accomplish the same goal of extinguishing these current excess reserves — though not cutting its own balance sheet — by raising required reserve levels — in other words, turn the current $1.49 trillion in free reserves into mandated holdings. It is hard to see how such a move would not be destabilizing, for multiple reasons, however. For one thing, it would represent a one-time windfall to the government for spending the money initially that found its way back into the banking system to be re-lent. Prices would, at the margin, be higher than otherwise, permanently. And, investors would likely reason the Fed and Treasury might coordinate to do this again, so psychologically it would be a terrible precedent.

Secondly, this move hamstrings commercial lending activity as surely as the Fed selling assets would be, and is ultimately more harmful to bank growth than any open market operations. This is so because in the latter case the participating banks at least would obtain interest-bearing assets in return for drawing down their own reserves. A freezing-in-place of current excess reserves would impinge banks’ degrees of freedom and deaden lending, freezing bank liabilities as well.

(3) The Fed could elect to increase interest payments on free reserves. This would also not shrink the Fed’s balance sheet assets, but would, like Option #2 above, immobilize these free reserves. Again, it is hard to see how financial markets would not react very negatively to this. As interest rates rose in the economy generally, this would become very costly to the Fed — and to the U.S. taxpayer footing the bill. Psychologically, paying banks not to lend after creating reserves to impel them to do just that would be seen as both self-defeating and a very transparent harbinger of future inflation. It might also over time prove to be very costly to the Fed. Currently the Fed is paying around $4 billion in annual interest, a small but significant aid in banking system recapitalization. But if interest rates move back to where they were in the “normal” 1990s, that $4 billion becomes $40-80 billion quickly, completely wiping out Fed profits. Again, the lending immobilization and hit to investor psychology would soon represent a serious toll on the economy.

Reform Is Coming to the Fed

Messrs. Herbener, Klein, and Taylor were all critical of the current Fed’s discretionary gambles in recent years, and Mr. Bernanke’s reliance on a “tallest midget in the room” argument that, given turmoil in Europe and slow-growth in Asia, demand for U.S. dollar-denominated assets would remain elevated for years to come — thus allowing the Fed to continue its quantitative easing programs. All three are wary of the license the Fed’s dual mandate gives to the Bernanke Fed to pursue further QEs; in their view, none of the three options above comes without risk, and indeed all feel further hard times are unavoidable as real losses on Fed holdings materialize. And at the least, current monetary policy, if unchanged, portends years of a sideways stock market, similar to 1966-83 here in the United States.

The crux of the matter, as Mr. Taylor reminded the subcommittee, is that the dual-mandate is itself riddled with an internal inconsistency, if not outright contradiction in mission. For a stable dollar presupposes accuracy in profit-and-loss accounting to promote maximal levels of job-creating investment. But QE programs enable the government-led distortion of profits and ability to hide (or, “socialize”) losses; that is to say, the Fed has itself created serious moral hazard in our financial system.

The late economist Herbert Stein once famously said that if something cannot go on forever, it won’t. As Congressman Paul’s subcommittee heard last week, a reckoning lies ahead, as pricing and investment distortions are promulgated by current policy that are only later revealed and corrected. It may not be as severe as, say, the current tragedy in Greece, but if policies of fiscal prudence along with improved economic growth in the U.S. do not soon materialize to allow for the Fed to unwind its current highly-leveraged balance sheet, years of a sclerotic economy are guaranteed, and a monetary breakdown cannot be ruled out, pending developments with current U.S. Treasury holders. All of this gives voice for calls to re-examine the sound-money policies of days long gone, policies that involved gold. These classical policies of sound monetary doctrine were summarized by Messrs. Herbener and Klein in their respective testimonies, and we examine these next week, for we are of the view that their return in some form is now axiomatic.

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, John Chapman can be reached at john.chapman@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com. The views expressed here are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect that of colleagues at Alhambra Partners or any of its affiliates.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

Stay In Touch