The heavy hand of Federal Reserve policy is apparent in the credit markets as intended. The Fed continues to follow a ZIRP approach that expects low interest rates to create credit production in the banking system that transitions to the real economy as either personal sector or business loans. The first part of that equation has conformed to policy expectations in each of the previous QE programs, so that the latest QE iterations would see much the same is far from unexpected.

QE’s are intentional actions taken toward managing expectations of future inflation. Given the historical relationship between monetary debasement and future inflation, the coincidence of monetary expansions and rising inflation expectations is unsurprising. In recent history, inflation expectations (at least those indicated by treasury breakevens) have followed monetary expansion programs, only to fall back at their conclusion. As we have noted previously, we think this a likely explanation for the now open-ended natures of both QE 3 and now QE 4.

Without a doubt, the Fed has had the most monetary success with inflation expectations. Every time a monetary program is believed imminent, inflation expectations have responded according to the historical narrative. Outside of inflation expectations, however, the results have been less than uniform.

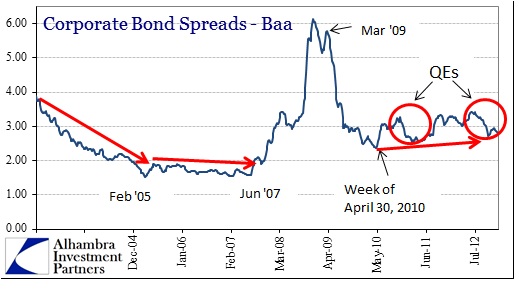

Risk spreads have largely conformed as have inflation expectations. So much of that is due to the flood of liquidity in markets (outside the banking system) searching for yield in any shape or form. While default risk has risen somewhat in 2012, Baa spreads have compressed according to monetary intentions.

In the longer-term context, however, risk spreads have a lot of compression left in order to conform to historical comfort. Given the ZIRP environment, it remains to be seen just how low nominal corporate rates can fall. But no matter the compression relative to recent spreads outside of QE’s, the overall trend in corporate spreads is certainly upward still.

In terms of economic expectations, the recovery narrative is felt through credit markets as an increase in interest rate expectations. In any kind of normalcy movement, whether organic or monetarily inspired, the time value of money would be one of the primary investment considerations in credit. In tandem with reduced risk expectations, we would also expect the time value to manifest into a steepening yield curve.

The main element of the treasury curve, where QE is most heavily present particular in the all-important on-the-run segment, is the 2-year/10-year spread where most of the “money” in the treasury market resides. The Fed has essentially telegraphed its intentions to keep ZIRP in place for at least another two years, so any “market” expectations for normalcy should be forming in the 2s10s.

Here we see the lack of real follow-through in the monetary program. Given the expected term structure of interest rates (if the Fisher structure is valid), we should expect to find those inflation expectations showing up in a far steeper treasury curve.

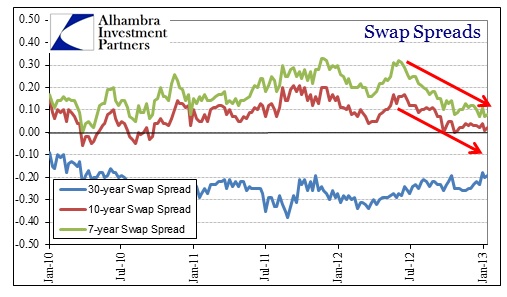

As much as the treasury curve steepness is not reflecting “favorable” or “normal” rate curve expectations, swap curves are completely contradictory. As we have noted previously, swap spreads (particularly the 10-year) have collapsed. Given how sensitive swaps are to future expectations of interest rates, a quicker or sharper return to a non-ZIRP environment should see a widening swap spread. Instead, there have been more numerous instances of negative 10-year swap spreads since the first announcement of QE 3 in September.

Given this apparent dichotomy among inflation expectations and swap spreads, it is not clear just how effective credit markets expect the heavy monetarism to eventually be. I would argue that swap spreads (given their massive size, institutional nature and furthest reach from outright monetary influence) to be far more attuned to investor expectations. Treasury bond prices themselves are likely reflecting only what the Federal Reserve wants to communicate to investors.

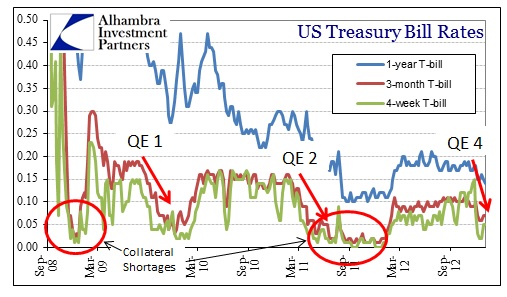

Beyond future interest rate and economic expectations, we have to note the potential for liquidity in the credit system. As we saw with QE 2, in particular, the Federal Reserve’s purchase of short-dated on-the-run treasury bills created a shortage in the financial collateral space (the only true interbank money in US dollar denomination) that directly weakened the rehypothecation chain of interbank liquidity. In short, the Fed increased the stock of central bank money but simultaneous removed the means by which it would have been moved outside of the primary dealer network.

The collateral shortage became apparent as t-bill rates fell to zero and even negative (as they had in the panic of September and October 2008). The shortage of financial collateral was certainly a major factor in the Federal Reserve re-opening dollar swaps with the ECB (among other central banks) since dollar collateral usage is prevalent in the European system.

In the wake of QE 4 (the unsterilized purchase of US treasury debt), t-bill rates have fallen back toward zero.

It is still far from certain that any shortage will manifest in the credit/wholesale system for dollars, but the initial stage suggests that this is certainly something to monitor as 2013 progresses.

Stay In Touch