The justification of ZIRP/QE has been largely based, in the real economy outside subsidizing bank lending, on the premise that low interest rates stir additional or incremental borrowing. The distortion of the domestic economy in the United States since the mid-1970’s toward consumption in the household sector has been a function of this assumed dynamic. It remains the textbook approach to monetary policy.

However, even the Federal Reserve has observed an atypical pattern response to its textbook monetary maneuvers. Low interest rates, often record low rates, created through the “emergency” measures of ZIRP and additional QE applications (up to four and counting) have not had the intended effect outside large corporate obligors and the Federal gov’t. The personal sector, the primary target of monetary policy, has been largely unresponsive to credit rate “stimulus”.

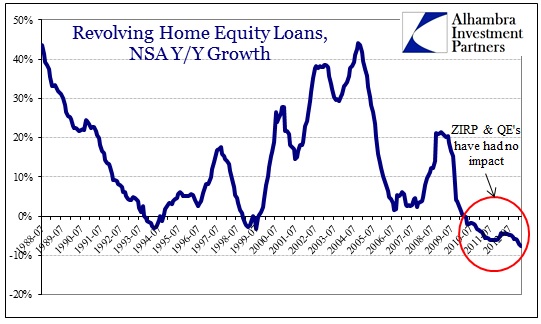

Home Equity loans to the personal sector amounted to about $25 billion total in 1987. At the peak in 2009, total revolving home equity loans grew to over $610 billion. Over that span, yearly growth averaged nearly 16%. In terms of accomplishing monetary stimulation, home equity credit is most directly tied to personal spending.

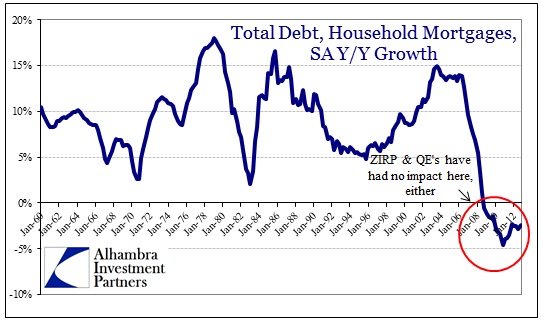

Record low interest rates have not been able to pull home equity credit out of its continued contraction. The same has been true of mortgages in general.

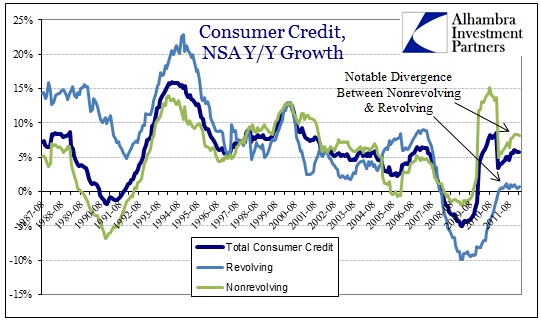

Revolving consumer credit, much like revolving home equity, has been constrained in the ZIRP/QE period as well.

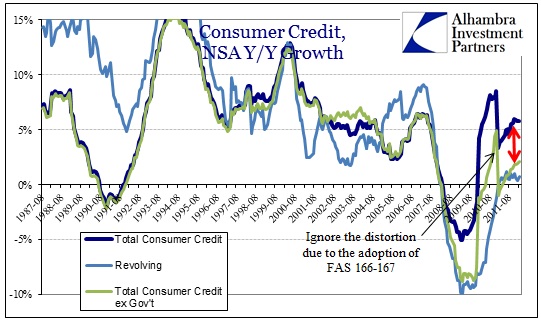

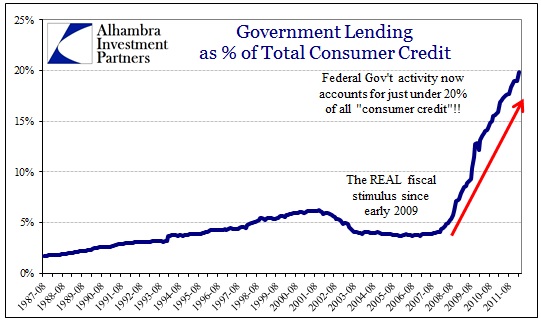

The relative rise in nonrevolving credit appears to conform to monetary expectations, but as is plain to anyone paying attention to the student loan bubble all of that credit growth is from the federal government’s coup de finance for private educational lending. Subtracting the absolute explosion in student borrowing from the federal government we see that a far different picture emerges.

It has gotten so out of proportion that the Federal government is now the only marginal source of “consumer credit”.

In short, borrowing at the personal level and/or through depository banking channels has been nearly non-existent despite all the textbook policy applications (there have been pockets of activity, such as nonrevolving finance of auto loans which has been significant factor in the resurrection of automobile production, certainly an economic positive but not so much as to bring auto production back to levels seen before the crisis).

This lack of direct monetary channel into the personal sector is well known to Federal Reserve policymakers. Ben Bernanke himself acknowledged this, at least pertaining to the housing market, in a February 2012, in a speech to the National Association of Homebuilders International Builders Show in Orlando:

“So why has the recovery in housing been so slow? One important factor is restraints on mortgage credit. Since its peak in 2007, U.S. home mortgage credit outstanding has contracted about 13 percent in real terms. In prior recoveries, mortgage credit had begun to grow four years after the business cycle peak–but not this time around.”

He went on to place primary blame on lending standards, the inevitable tightening of credit channels after such a sustained period of overly and often ridiculously loose standards. The changing lending standards regime has been a procyclical counterforce to monetary channels for as long as banks have been a large part of the business cycle.

To that point, however, there is a contradiction in the publicly held reasoning for ZIRP/QE. The Fed knew lending standards were going to tighten in extremis and that “pushing” credit to where it is needed (from the textbook perspective, anyway) most was an operational long-shot (at best). That leaves direct credit out of the recovery playbook altogether, and the data shown above demonstrates that rather conclusively.

Again, this was not a surprising development for anyone at the Fed. Their primary expectations were actually directed toward the “wealth effect”, in that monetary policy is/has been more about psychology in the personal sector than direct money. I have said repeatedly that there is no money in monetary policy, at least since the rational expectations theory was adopted as a core tenet of modern central banking doctrine in the 1980’s.

Where actual credit is flowing is to large obligors – liquidity preferences are alive and well, something Bernanke knows well from his academic studies. He even acknowledged as much in that Orlando speech to homebuilders:

“Nevertheless, REO-to-rental programs appear to have some potential for success. As of early November 2011, about 60 metropolitan areas each had at least 250 REO properties for sale by the GSEs and the FHA–a scale that could be large enough to realize efficiency gains.”

My colleagues Joe Calhoun and Doug Terry both noted the “strange” occurrence recently of Blackstone Group getting far more funding than they asked for in the REO-to-rental space. The private equity firm, in sharp contrast to the personal sector, had no trouble from Deutsche Bank increasing its line of credit from $600 million to $2.1 billion.

Marginal credit in this monetary schematic only flows through the largest obligors or institutions (including government). There is nothing at the lower end or smaller scale. Banks want to syndicate (where they used to securitize) or leave it up to the federal gov’t – in either case only size matters. That might “work” for education loans apparently in lieu of jobs (students staying in school on borrowed federal funds, financed by the interest rate target of the Fed funds), but this is a separate form of “trickle down”, distinct from the largely fiscal policy of tax cuts in the early 1980’s. In fact, this new form of trickle down is downright Keynesian. There is no room left for true markets, true capital or true savings.

Expand the government and give “liquidity” to the largest banks and institutions, expecting some leakage that encourage bad habits (spending rather than saving to repaid household balance sheets) to those that have no direct outlet to all this “stimulus”. An ocean of credit for the big players and pop psychology for the general public.

A proper, healthy economy functions on merit and relative “value”, not size.

Stay In Touch