Getting into the arcane accounting of central banks is a chore, but, in an uncertain world with every central bank “doing something” at exactly the same time, it is a vital task that requires patience. A lot of patience.

Central banks all have familiar financial disclosures and statements. The Fed, ECB, SNB, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, et al, have income statements and balance sheets. The income statements are largely meaningless in the context of monetary policy and banking. The balance sheets for central banks convey some information, but largely derivative about certain specific programs or snapshots of policy measures.

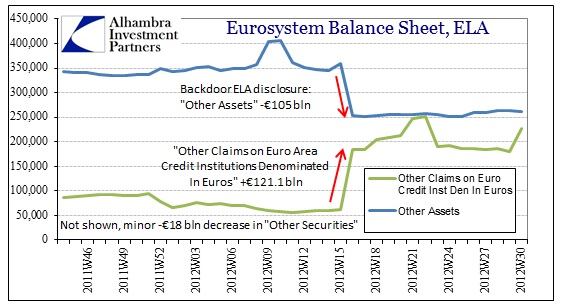

For example, in its April 20, 2012, weekly financial statement (balance sheet), the ECB disclosed an accounting change for a couple items on the asset side. It involved moving an account from “Other” to a more (still not fully) disclosed, transparent line item. In response to questions about the Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) program, the ECB responded with balance sheet recalculations.

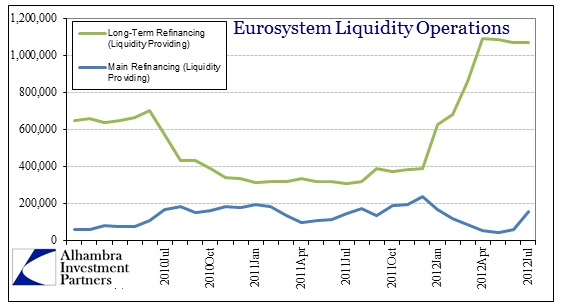

This move, not unnoticed by the financial community, disclosed ELA usage far above what was expected, particularly given the circumstances surrounding the recent completion of nearly €1 trillion LTRO’s.

From that point forward, attention to bank liquidity in Europe resumed with a vengeance. But from the standpoint of liquidity, it is hard to gauge anything from the standalone balance sheet of the Eurosystem.

NOTE: the balance sheet here is not the ECB balance sheet, per se, it is a consolidated look at the combined balance sheets for the entire Eurosystem including all the individual National Central Banks (NCB’s).

The LTRO’s themselves looked impressive in isolation.

But there is not enough information given here to complete the liquidity picture for the overall banking system in Europe. Fortunately, we can use the “Simplified Balance Sheet” that takes relevant pieces of the overall balance sheet and condenses them into a unified account of overall liquidity.

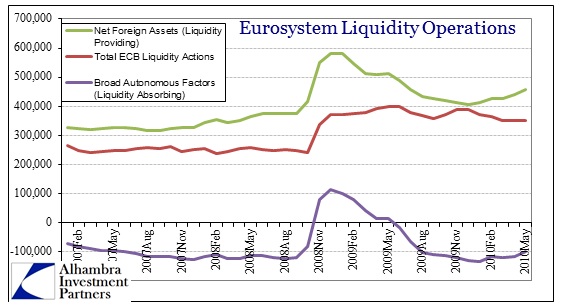

On the left side are all those accounts that “provide” liquidity, including the LTRO’s (under the “Long-term refinancing operations” heading). On the right are liquidity “absorbing” factors, including two accounts used by the ECB to drain “excess” liquidity, ie, sterilize.

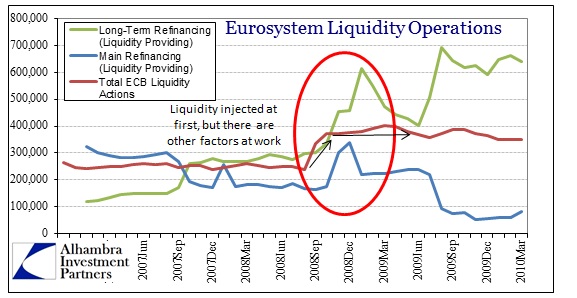

Filling out the LTRO picture, we see that offsetting absorptions made for a much more modest ECB contribution.

The redline denoting “Total ECB Liquidity Actions” shows exactly how much impact ECB measures were having on overall liquidity conditions in the banking system. Up to the end of 2011, the ECB was actually absorbing liquidity as other factors were involved to a greater degree (as we will see). From December 2011 through July 2012, the LTRO’s added only about €200 billion in additional overall liquidity. A good portion (€518 billion) of the rest was “absorbed” by the short-term deposit facility.

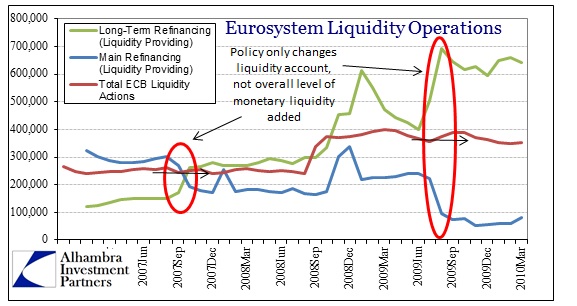

If we step back and look at the ECB action throughout the crisis period, we actually see a concerted effort to maintain a stable level of intervention – with one exception.

In August 2007, the initial ECB reaction to the eurodollar and unsecured lending freeze was not to “inject” additional liquidity, but to transform maturity in interbank lending. The main refinancing operation was reduced as the ECB offered a 3-month, €40 billion allotment. The overall action in terms of changing liquidity conditions was minimal, only the maturity of ECB programs actually changed.

The same kind of program was undertaken in the summer of 2009. Maturities were extended across refinancing programs when the ECB announced a June 23, 2009, long-term refinancing program at full allotment (meaning no preset limitation, all bids at the stated interest rate were honored) for both three-month and one-year terms. The bulk of those bids came out of banks in the overnight MRO’s.

For the most part, bank “reserves”, or what the ECB and Eurosystem call the “Current Account” are relatively stable. The only significant changes to the current account related to the LTRO’s and then the ECB’s decision to eliminate interest on the deposit account (liquidity absorption) later in 2012.

The exception to these “sterilized” programs was the last three months of 2008. Here both refinancing programs were “allowed” to rise as the ECB sought to counter rapidly progressing illiquidity in interbank markets.

From October to December 2008, the ECB increased allotments in the main refinancing by €163 billion and the long-term refinancing by €123 billion. Offsetting some of that increase was usage at the deposit facility, absorbing €180 billion of that liquidity as banks parked “excess” cash with the ECB rather than lend in the illiquid and uncertain interbank markets. They could have left them in the current account (bank reserves) but the deposit account paid a positive interest rate at that time making it a very attractive “risk free” asset (liability for the ECB).

We still, however, have an incomplete picture of overall liquidity in the Eurosystem. To this point, I have only shown ECB-driven operations and accounts. In addition to the ECB actions, there are “autonomous” factors and “net foreign assets” – accounts that are not directly related to monetary and liquidity policies, but have an impact on overall liquidity conditions in the banking system.

Net foreign assets mostly consists of the NCBs’ gold holdings (including gold “receivables”) and foreign currency “reserves”, both revalued on a quarterly basis at that time. The offsetting factor, “broad autonomous factors” is a bit more complex.

Autonomous liquidity factors include banknotes (currency) and central government deposit balances at NCB’s. “Broad” autonomous factors relate to residual foreign assets along with domestic portfolio balances at individual NCB’s (all netted). The word “autonomous” means exactly that, that the ECB has no control (or at least takes no responsibility) over these accounts. Since these factors are determined by the public (as in banknotes) or by institutional arrangements, ECB influence is largely non-existent.

Where this “autonomy” factor classification is more ambiguous is in the case of possible direct central bank intervention in currency markets. Here, the ECB (or even the NCB’s themselves) might have influence or even some direct program, but it may not at all relate to monetary policy specifically, therefore it would count, in terms of systemic liquidity, as an “autonomous” factor.

In terms of the crisis in 2008, net foreign asset balances rise dramatically as do “broad autonomous” factors, absorbing some of that rising liquidity due to foreign reserves and gold (more the former than the latter). What is odd is that the track of “broad autonomous factors” mirrors the overall crisis in Europe, including the overall pattern of rising and falling euro prices, rather well.

There seems to be a very direct correlation between both crisis and the fall of the euro with the absorption of Eurosystem liquidity here. Exactly why is not at all clear because of the opacity and esoteric nature of this central bank accounting. Just like the ELA balance before April 2012, there are a number of factors involved in this autonomous factor, and thus a number of possible explanations.

Given that we know this calculation largely rests on net foreign assets and liabilities, it may be the institutional flow of currency deposits across boundaries, but we don’t know either which assets or which boundaries. It could be into the USD, CHF, or JPY, or a number of other denominations (or a bit to all of them). It could also be portfolio changes at the individual NCB level, but most of those changes were legacy accounts from the switchover to the euro, so I don’t think that is highly likely scenario. Further, any emergency liquidity activated by the NCBs directly would not be included in “autonomous” factors.

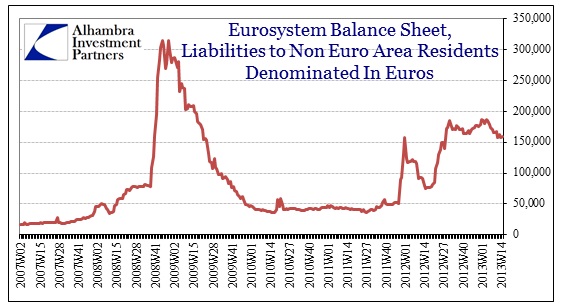

Whatever the reason, the trend has been broken surprisingly toward increased liquidity absorption well past July 2012.

Such a large rise in this absorption factor has been associated with growing illiquidity and crisis flares – the opposite of what we have seen in the second half of 2012 and early 2013. Either that means there are still crisis legacy effects particularly with foreign exchange and foreign institutions, or some dramatic paradigm shift in the liquidity system for Europe (due to some “autonomous” policy shift?).

While there is no way to know for sure given the incomplete information at hand, it bears keeping in mind that a liquidity absorption factor moving in this direction of this magnitude is equivalent to a €300 billion increase (since mid-2011) in public holdings of currency or banks parking idle funds in the deposit account. But since this is taking place in this “broad autonomous” factor, we can only speculate as to whether it relates to foreign exchange, particularly direct intervention at some central bank level inside the Eurosystem. If this is actually taking place, then we would expect the ECB to exchange currency or some other asset for a liability account (liquidity absorption) with firms/individuals outside the Eurozone.

Again, this is just speculation about movements in liquidity that do not make sense inside the “normal” context of Eurosystem operations. The last chart I posted above does add some evidence, though the correlation is far from exact, that this is a plausible assertion. What we do know is that something unrelated (at least directly) to ECB monetary policy is changing the liquidity needs of the Eurosystem in a rather significant manner. It could very well be exchange intervention.

Given all that has transpired and the curious timing (July 2012) of the surge in this absorption factor in the context of Mario Draghi’s promise to “do whatever it takes” to save the euro, you do have to wonder what has gone on behind the curtain of central bank secrecy. As the ELA disclosure showed all too well, the ECB is comfortable with hiding policies.

Stay In Touch