I’m not sure how much this can pass for shared wisdom, but somehow central bankers have become concerned about central bankers. This situation has been described and discussed ad nauseam since Japan first went full ZIRP in 1999. For all that supposed self-reflection, nothing has really changed except the rhetoric – and only recently.

“This is a world which places too much of a burden on central banks,” said El-Erian, the former chief executive officer of Pacific Investment Management Co. and now an adviser to Allianz. “This is a journey, not a destination. If the journey lasts too long, central banks go from being part of the solution to perhaps being part of the problem.”

The idea of “being part of the solution” sounds uncontroversial until you start to unpack the idea in more detail and to its logical ends. If your solution is to rebuild the financial system so that it can fully operate, once more, as an unfettered tool of statist economic central planning, then Mr. El-Erian’s description is enough. However, we are very much living through the lengths by which that operative theory is so very short of exhaustive.

“Savers are keeping too much money in bank accounts” and short-term bonds, Fink said. That is “exacerbating anemic growth and consumer consumption throughout the world.”

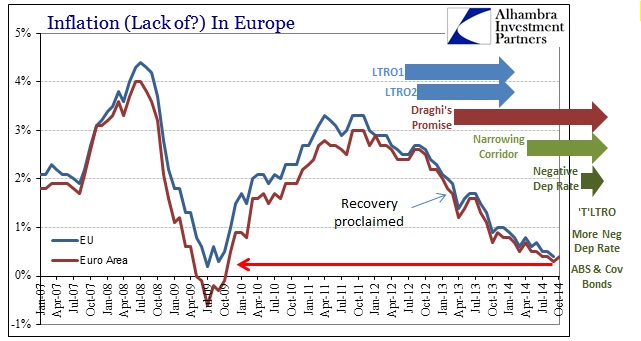

That is according to orthodox theory, but almost every indication in the actual financial world is saying Fink has the cart before the horse. This is a particular problem and relates back to El-Erian’s formulation, which is the operative end of “secular stagnation.” Central banks wish to “enforce” a “portfolio effect” not just on financial firms but also individuals by repressing savings yields, among other tools. Yet, the more repressive they become the more “too much money in bank accounts” is yielded.

What happens at that point? Even more repression until the point that “somehow” “central banks go from being part of the solution to perhaps being part of the problem.”

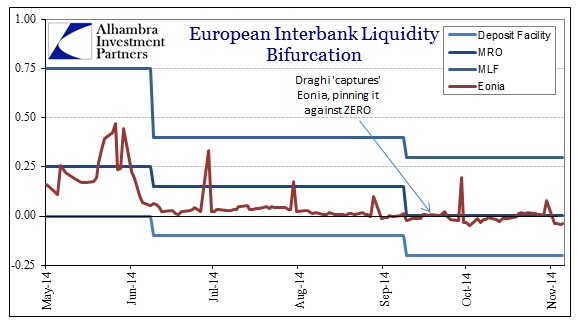

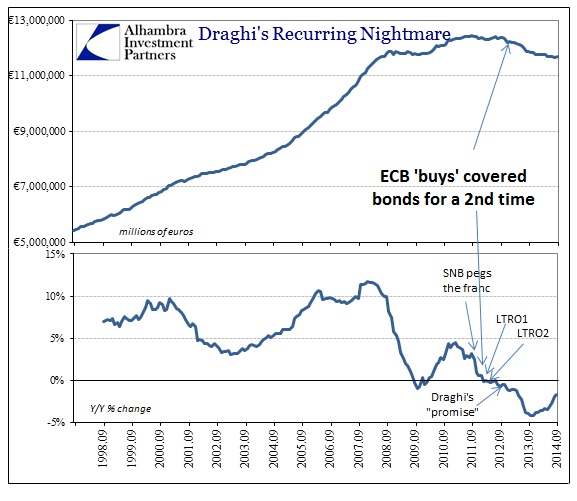

Having spent enough time on this in Japan, we can see it clearly in Europe too. The ECB has been repressing rates for a long time, as has every other central bank, to the point that they went negative first. The results of that repression are clear, simply pushing more of the same toward Mr. Fink’s mistaken orthodox ire.

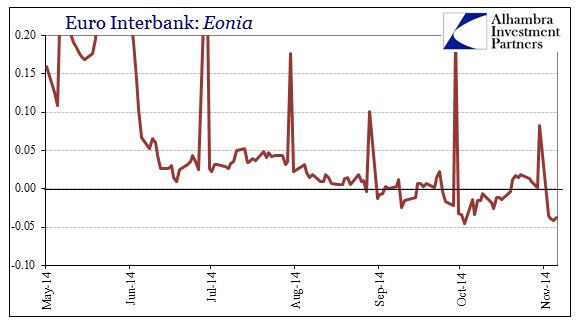

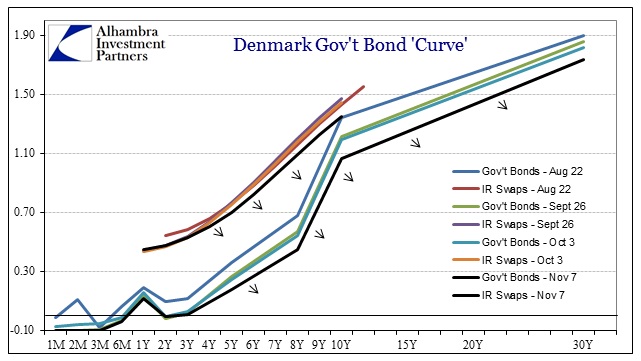

This happens, as I mentioned, both big and small, as it is not just interbank markets that respond to central banks by doing the opposite of what central banks intend for them. While there are ebbs and flows here like any financial feature, there is an unmistakable essence of repression occurring all across European credit again in November.

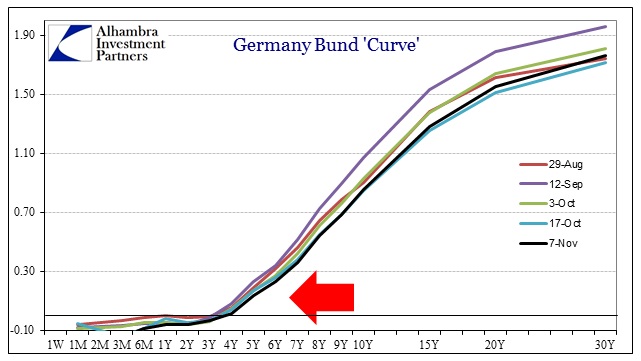

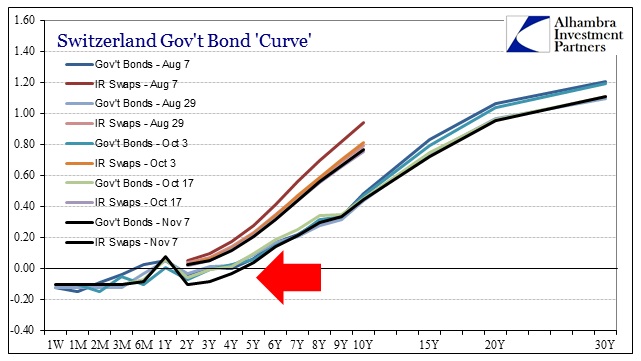

The bulk of investment is such that whatever the ECB is trying is not convincing at all in 2014, so much so that the more Draghi and his band try to fix the problem the more “investors” believe there is a problem (or that it might grow far worse and beyond any actual control input). Short-term “money” all across Europe right now is bleeding outside the euro or to at least Germany. Curves have drawn, somehow, still lower in almost every “shelter” location (which includes Eonia noted above).

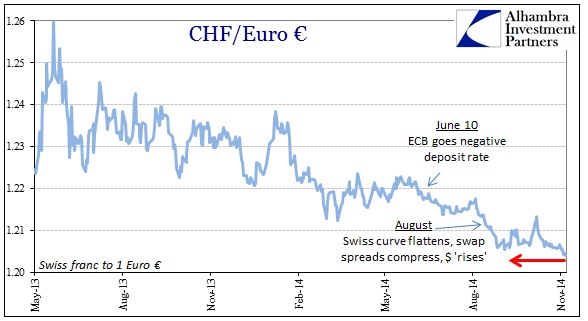

The Swiss franc has risen to the “strongest” level going back to the actual 2011 crisis. Clearly there is not a lot of faith in the euro at the moment, despite (or because of?) all of the ECB’s “latest” activities (which are all repeats of previous “ideas”, bringing up another factor of “markets” cluing in that central banks just may have run out of tools, instead just reusing in the hopes nobody actually notices).

The problem here, however, goes beyond just signaling and market interpretations. I have said repeatedly that I think Europe is getting to the stage where the ECB’s “journey has lasted too long” without anywhere close to enough successful imprint.

In that respect, it isn’t that “markets” want the ECB to do more, but rather that they would prefer they do something that might actually work; now growing impatient to the point that more than a few question whether the ECB can ever do that. In that respect, this central bank has lingered too long as the “only game in town” whereby it has revealed its own impotence. The more they linger in that position, the more transfers to that other side of “too much savings.” It all snaps once critical mass is reached, which is why I think there is more than a little desperation in the pace and rush to each of these rewarmed policies. At that point the major concern will no longer be “too much savings” but rather how much artificial pricing, especially in sovereign debt, might be revealed again, and how quickly that develops.

The answer is far simpler than any of those orthodox viewpoints can process, namely that monetary policy is, especially repressive in nature, not just ineffective but a full part of the problem to begin with. When the ECB went negative back in June, I described it as the system turning on itself. Now we get to see that theory in action, if only orthodoxists could stand to witness it in more than brief outbursts.

Stay In Touch