One of the primary pillars of even the tepid “recovery” of this cycle is undoubtedly auto sales. We can have a debate as to the influence of monetary policy in this arena, especially as auto loans have (along with student loans) been practically the only direct conduit of credit into the real economy. Clearly, despite the heavy flow there, auto spending just isn’t leading to downstream economic success as theorized by the concept of “aggregate demand.”

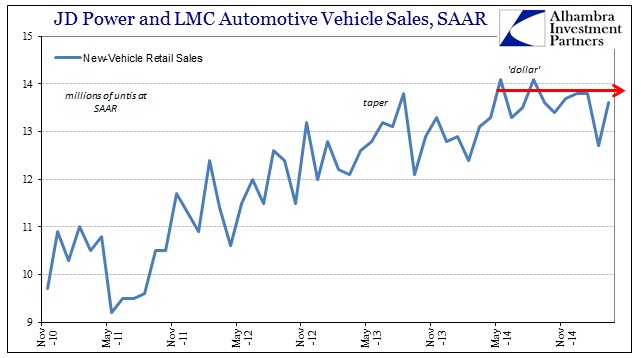

It should also be considered that the tremendous growth in the auto industry since 2009 is as much related to the immensity of the collapse during the Great Recession. On a purely growth basis, then, despite the huge gains apparent in the year-over-year rates auto sales levels are just now getting back to the prior cycle peak. Like labor utilization (full-time employment and hours worked), that observation actually suggests that autos have underwhelmed what you would expect of an ordinary V-shaped cycle.

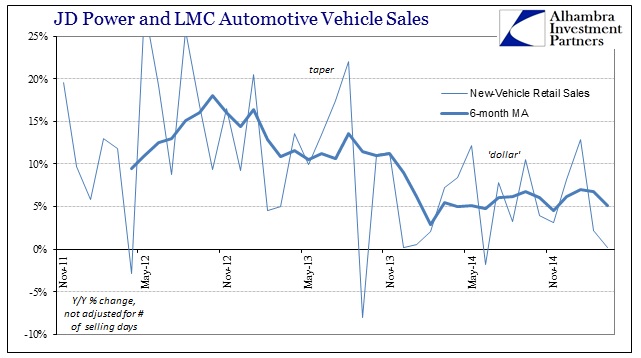

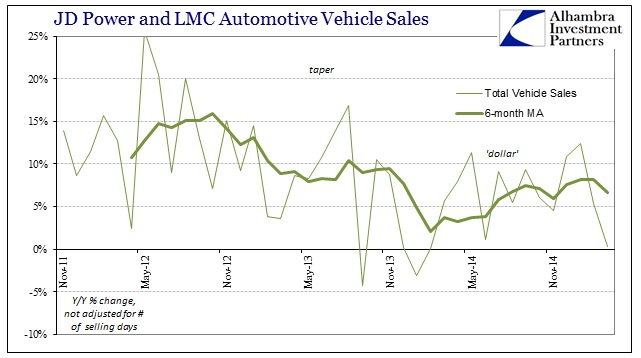

That may suggest any slowdown is itself a product of natural progression from a deep slide, but the timing of these possible inflections might argue more toward a cyclical explanation. More recently, auto sales have begun to slow, starting around the middle of 2013 – coincident to the grand “taper selloff.”

In 2015 so far, according to JD Power and LMC, January was robust but February and the estimates just released for March are decidedly not. That raises the worrying prospect of perhaps the “dollar” weighing now on autos too, which would undercut that primary aspect of consumer “demand” against a backdrop that is already slowed and uncertain.

The March figures are only estimated based on the pace of sales through March 11, which is already a problem if the trend like February holds – the first estimate for February was for a new car pace of 13.5 million SAAR but is now estimated significantly below that at 12.7 million (total vehicle sales first estimate was 16.7 million, revised down to 16.2 million). As you would expect, snow is being blamed for the discrepancy in the month, and we will see how it plays out in March, but even if the current estimates hold up they represent essentially no sales growth over March 2014.

Using the adjusted figures, new vehicle sales clearly have flattened out going back to May; which means the “dollar” may be playing a role in auto sales. Actually, it would be more exact to suggest that the “dollar” is picking up this slackening in “demand”, of which autos would certainly be a big part.

To the FOMC’s 2015 rate-hiking proclivity, there are all sorts of data now about how consumers aren’t willing to be further indebted beyond autos and schooling. The other side of that is, by and large, households are only spending what their earned income gives them. Without major and sustained wage growth, subject far more to inherent dynamism than credit conduits, the economy remains stuck in listlessness.

The link between earnings and consumer spending has been tighter in this expansion than in any other since records began in the 1960s, according to calculations by Tom Porcelli, chief U.S. economist at RBC Capital Markets LLC in New York.

Wages have become even more critical as households, still shaken after being caught with too much debt when the recession hit, remain unwilling or unable to tap home equity or let credit-card balances balloon to buy that new television or dishwasher. By not overextending themselves again, Americans are only spending as much as their incomes will allow, meaning that 70 percent of the economy is riding on how fast pay rises.

There are a few fallacies in those paragraphs but you get the point. Further, the calculations presented largely match widespread observation as it remains hardened against the Establishment Survey and the unemployment rate. Lackluster spending is a product of lackluster wages regardless of any “wealth effect” of asset inflation, which renders almost all of monetarism impotent (which the FOMC has finally admitted).

In the context of the possible slide in auto sales, however, that would suggest, as again autos have been the one area where indebtedness has not been a problem, perhaps a worsening trend for wages. That would mean, potentially, that this growing “slump” is deeper than even advertised to this point.

This may be a temporary pause for whatever reason, though I find it highly suspect that the erstwhile unbreakable trend in auto sales may have run up against a slackened pace at exactly the time when the “dollar” signals increasing financial worries about economic prospects. The high degree of correlation between consumer spending and household earned income only solidifies those worries intuitively. And it isn’t exactly “unexpected” to see artificial economic trends come undone as whatever propping them up is as well.

The last outcome the FOMC needed to oppose its optimistic view is the bedrock of autos. The next few months will be important toward determining just how serious all of this may be; though we could easily say that the “dollar” and oil are already on record.

Stay In Touch