The ongoing money market adjustment remains ongoing; perhaps that tautology is the most that can be interpreted from continuing mixed signals to this point though the longer nonconformities continue the more innocence is threatened. Recognizing again that this is still early in the process, there are some indications that resistance is real and even understandable. That begins first with the very question as to how we might figure what T-bill rates “should” be in the first place. From that follows observations about repos and reverse repos.

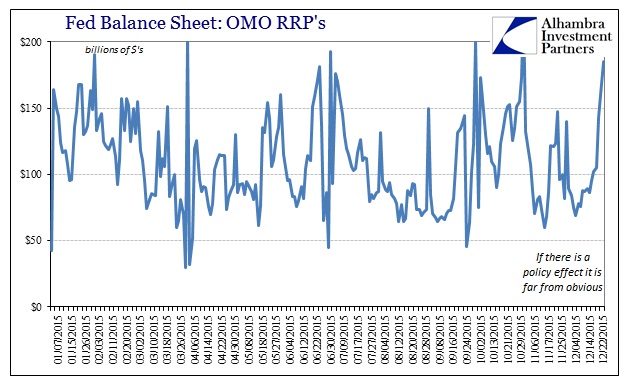

The Fed’s RRP took in $185.35 billion from 60 bidders today, up from $160 billion yesterday and $143 billion Friday. Still, however, those totals are within the range of what we have already seen in RRP this year (not counting quarter-end), representing nothing yet of additional liquidity being “drained.” For instance, there was $173 billion in RRP’s on October 29 and $225 billion the next day, $176 billion on July 2, $190 billion January 30 and even $168 billion January 22. If there is some escalation in FOMC-commanded “tightening” it is at this point trivial and arguable.

From strictly the perspective of T-bills, as an almost cash substitute with some price risk attached yields should be dependably above IOER and the “lower federal funds boundary” established by this new corridor approach. If faced with the strict alternative of “lending” cash to the Federal Reserve overnight or the US government at an interval of even weeks or a few months you pick the former every time. Thus, if IOER and RRP’s are set at 25 bps there isn’t a theoretical foundation for bills to trade below that.

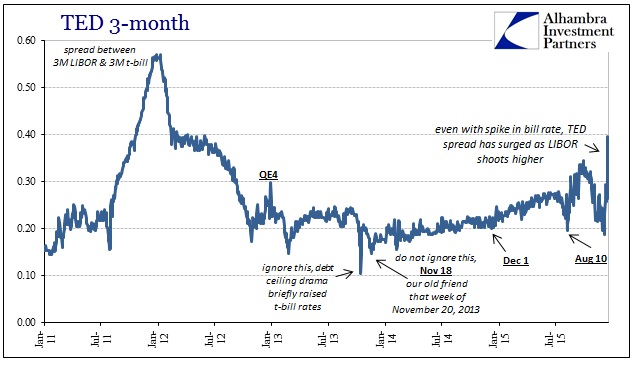

Further, we can infer from other market spreads about where bills “should” be trading according to monetary policy. If the FOMC is correct in its economic interpretation, the TED spread should only adjust by the smallest of increments. A policy measure that confirms the “booming” economy would leave some additional risk but only insofar as money market counterparties would like to factor less explicit support for liquidity (which assumes, mistakenly, that central banks actually supply or manage it similarly).

The TED spread in the past few days has, however, exploded again. That is primarily due to the reasons we are discussing here – namely that LIBOR has “behaved” but bills have not.

At nearly 40 bps last Friday and again today, TED is far out of proportion even to the rising features of the past year. The spread has averaged between 21 bps and around 27 bps more recently. That range is matched very closely by historical precedence from the last time the FOMC attempted money market “tightening” in 2004. Then, as now, TED spreads though much more volatile averaged about 20 bps in the “ultra-low” period and then rose, on average, to nearly 30 bps into the “tightening” regime.

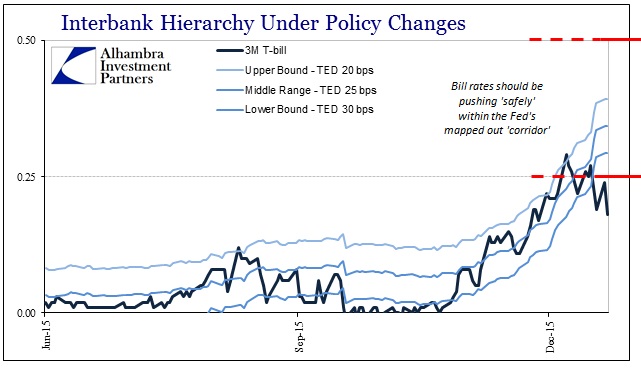

If we assume LIBOR is behaving as the FOMC intends, then we can extrapolate from that via TED what the bill rate “should” be. In fact, as I have done below, we can model upper and lower bounds by the historical experience with average TED to define if not a corridor then at least a loose range of where bills would have to trade to be conforming to policy intentions.

This confirms the idea that bill rates are too shallow, having turned so just as the FOMC became ready to actually take the step in raising rates this time. In other words, the 3-month bill was actually proceeding as it was “supposed to” until abruptly departing that expectation around December 8 (when the junk market was in full disarray). Since then, not only has the 3-month bill gone from the upper to middle to lower bound in our TED-defined range, it has shifted far below any of it for all of the days actually on this side of the FOMC decision.

This is certainly not conclusive, but it is quite reasonable and compelling evidence that money markets are not conforming in full to the FOMC intentions. Since we are speaking repo and T-bills (thus, collateral), it may fairly be argued that the more vital and dynamic sections of the money markets are as yet revolting while the more “dead” and distant markets are all that have behaved. There is more evidence, too, along those lines along with some important implications should it continue (subscription required).

Stay In Touch