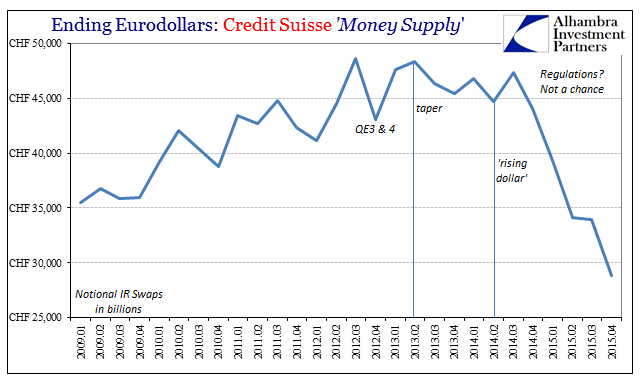

Credit Suisse released its annual report for 2015 today allowing us to update its progress through winding down its eurodollar activity exposures. As expected, the bank’s gross notional balance sheet offerings declined by quite a bit in Q4. Gross notional interest rate swaps fell by 15% from Q3 to just CHF 28.8 trillion, the largest quarterly decline (in percentage terms) in the data going back to 2009. Since Q3 2013 and the start of taper (end of the QE as supposedly “open ended”), Credit Suisse’s IR notionals have declined by 40%. As you can plainly see below, regulations don’t seem to playing any role whereas obvious market events and timing matter:

As if we needed further evidence beyond the regular and painful turmoil that keeps Credit Suisse in the news, this curtailment, undoubtedly being accomplished via compression trading, coincides exactly with the “rising dollar.” Since, as noted yesterday, CS had as late as early 2014 made a point of emphasizing growth through “high returning yield businesses” we can infer that interest rate swaps were trading and liquidity offerings to compliment that overall position – at the worst possible time to be offering anything.

The derivatives book(s) may not directly declare the extent or even the nature of this sudden disfavor. Despite likely being heavily on the “wrong” end of all this, that doesn’t necessarily lead to losses; in fact, it is never losses that cause the most problems except at the end. The issue is liquidity and from certain perspectives we can figure out the negative effects, and thus why CS (and its peers) are very keen on exiting and cutting back resources, risk-weighted assets, and jobs in investment banking.

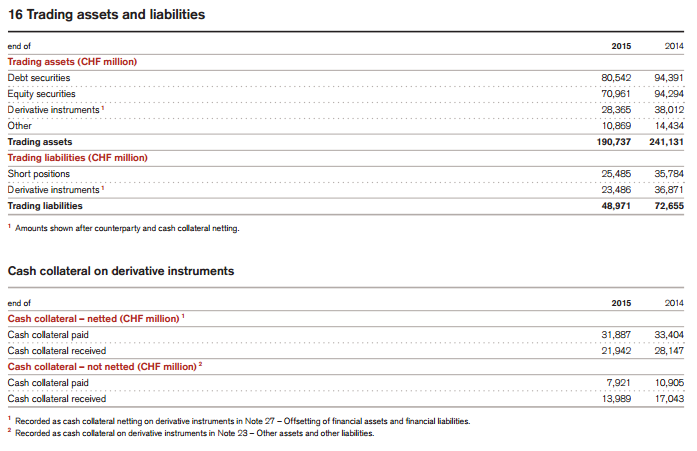

This is not a perfectly comparable estimation as it conflates several functions, but in general terms we can see some of the liquidity impact on CS from its derivatives book. Not only does the bank show large declines in both trading assets and liabilities (fair values, not notional) in derivatives, the change in collateral is rather stark. In 2014, CS received CHF 45.2 billion in collateral (both netted and not) against collateral paid of CHF 44.3 billion. The events of 2015 shifted that position to CHF 35.9 billion in collateral received against CHF 39.8 in collateral paid.

The difference, essentially a CHF 5 billion collateral call, was in contrast to prior years where reported derivatives collateral was more balanced and even. In 2013, the bank reported CHF 32.23 billion in collateral paid against CHF 32.16 billion in collateral received. So while CHF 5 billion does not seem a monstrous burden to a bank (though seriously shrinking) with total assets of CHF 821 billion, it is a significant change with regard to that method of funding since additional collateral paid out to counterparties typically becomes encumbered. On its liability side, CS shows only CHF 46.6 billion in central bank “funds” purchased and repo, meaning a CHF 5 billion drain in potential collateral is a relative hardship, stamping further urgency beyond just further risk in the derivatives book.

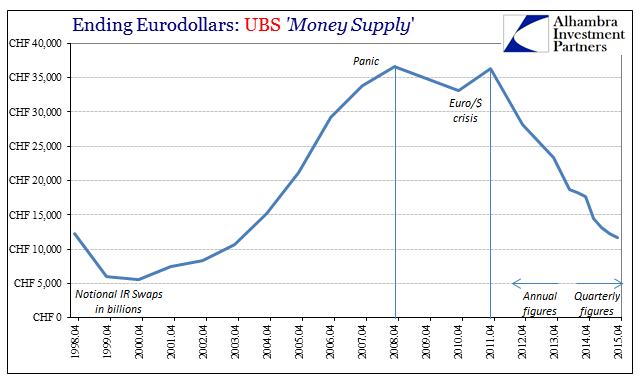

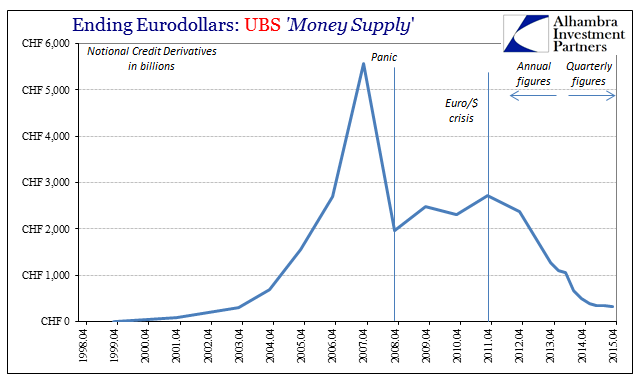

Compare all that to CS’s closest competitor, UBS. Unlike Credit Suisse, UBS has not generated anywhere near the drama and excitement of its Swiss cousin. That doesn’t mean they are not attempting the same strategy, only that UBS put it in place long before Credit Suisse has been forced to. UBS’ investment banking business has been hit by all the same problems as all the rest of the investment banking, eurodollar-making class but not to nearly the same extent because their downsizing and restructuring was already done (though it may suggest even that wasn’t enough).

Rather than wait on Bernanke/Yellen to deliver, UBS took the 2011 crisis for what it was – a signal that eurdollar banking as it once existed, where growth and size were the only defining qualities, was never going to rematerialize. Thus, while UBS has had a few bad quarters here and there, the bank has also fared much better over the past two years than those banks that looked past 2011 to the illusions of QE. In fact, by the latter half of 2015 most commentary about Credit Suisse was derived from UBS’ past experience where it had already cut the investment bank before it spilled into the worst of the latest bubble period.

From last October:

Some analysts noted that Credit Suisse’s planned investment-banking cuts, which will reduce the amount of risk-weighted assets in the unit by about a fifth, will disappoint those expecting the same dramatic restructuring completed at rival UBS Group AG. UBS has won plaudits and investor confidence.

Mr. Thiam drew a distinction with UBS, saying that Credit Suisse’s decisions were tough because “our investment bank makes tons of money.”

Thiam would probably revise that last comment especially given recent circumstances. As usual, the article quoted above goes on to direct these measures toward “increasingly strict regulation” while ignoring the screaming certainty in the timing of all them. In other words, once more economics and its media prove to be the opposite of science, as it just “can’t” be a worsening fundamental climate with very dire monetary implications because the economy is recovering fully and markets are as a robust as ever – apparently we live now in a world of only anomalies. There is no evidence for any of this, mind you, except an unemployment rate that stands all by its lonesome; leaving the vast catalog of economic and financial evidence of very real economic decay and dangerously growing financial imbalances as somehow the sole and fruitful work of Basel III. Economics starts from what “should be” even if it has to dismiss “what is”, an absurd proposition made all the more so when, as with the Swiss banks, the true reasons could not be more obvious and forceful.

Stay In Touch