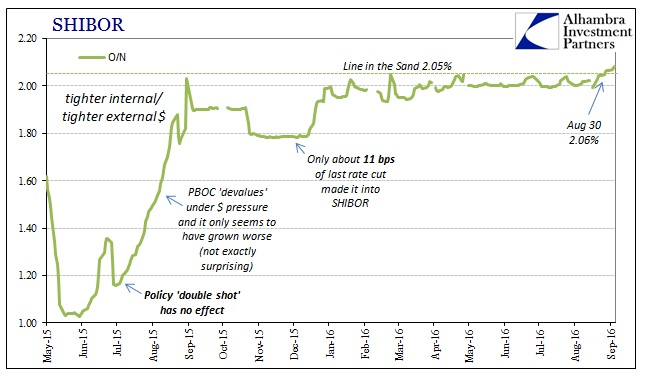

On August 30, the overnight SHIBOR rate jumped above 2.05% for the first time in more than a year. As the acronym indicates, SHIBOR is to Chinese RMB interbank liquidity as LIBOR is to eurodollars in London. In the summer of 2015, SHIBOR began rising steadily and often precipitously despite monetary policy “stimulus.” On June 27, 2015, the PBOC cut the benchmark lending/deposit rate by 25 bps while also reducing the required reserve for Chinese banks. Despite the policy “double shot”, O/N SHIBOR was only temporarily diverted and soon resumed its troubling trajectory.

Since the Chinese economy is funded in externalities (especially “dollars”) as much as internal bank reserves and true money policies, the problem of SHIBOR was revealed as a function of increasing pressure placed on the Chinese system as a result of the then building “dollar” run. In response, dating back to that March, the PBOC had pegged CNY exchange as a workaround, increasingly stamping out any volatility in CNY (to the dollar). What that really meant was that the PBOC was attempting to fill the funding void left by Chinese banks unable to pay the required premium (in lower CNY exchange) to bid in eurodollar markets (repo, unsecured, FX, etc.).

But as the Chinese central bank was actively using its wholesale “dollar” means it was at the same time restricting RMB liquidity. Thus, it was established that because of this money market arrangement (external/internal) the PBOC can only pick one to control. Of course, for a time in August 2015, funding pressures had become so disorderly that the Chinese had control over neither – and it was within this exact period that global markets (mini) crashed the first time.

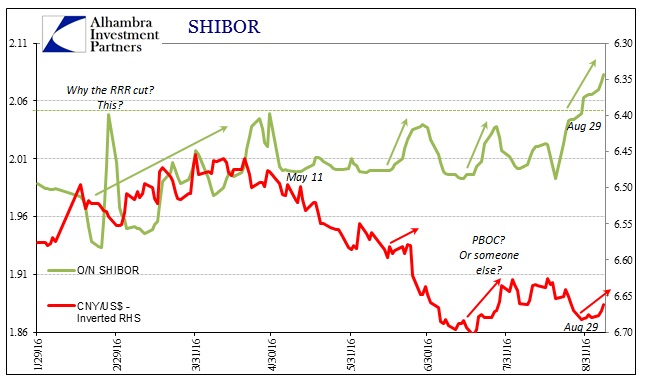

In early September last year, the PBOC began to run what was surely a policy adjustment; making tradeoffs between SHIBOR and CNY such that neither one gets too far out of hand. In terms of CNY, the slide in November and December notwithstanding (as another example of being out of control), that meant deferring to SHIBOR such that whenever the SHIBOR rate rises above 2% and really closer to 2.05% the exchange CNY rate is “allowed” to fall as an external funding counterbalance.

I still have no idea why they picked 2.05%, but it is absolutely clear that was the Chinese policy line in the sand – until August 30.

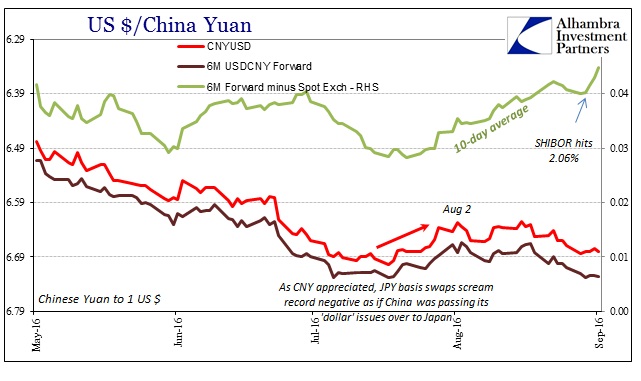

As overnight SHIBOR now rises steadily, hitting 2.083% today, CNY remains steady to even upward and upending almost a full year of very predictable operation. It’s as if the PBOC is suddenly more afraid of 6.70 to the dollar in exchange than 2.05% in overnight RMB. The trillion dollar question is “what changed?” There are some clues (FX) as to what that might have been (subscription required) but in the end they all still point to “dollars.”

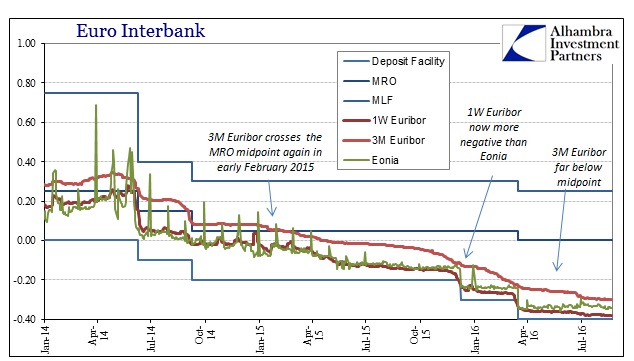

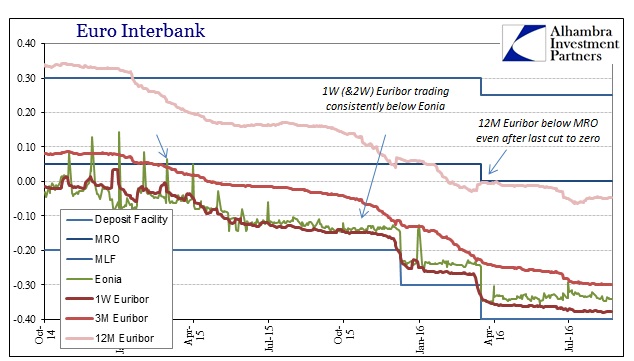

Inverse to the Chinese money markets are those in Europe. The ECB contrary to the PBOC has the problem of negative money rates that only get more negative no matter what it does. Further, none of these increasingly negative rates makes any sense, in some ways similar to what SHIBOR in relation to CNY is supposed to reflect. In other words, the ECB uses its midpoint rate (MRO) as its main monetary policy lever, yet of late even 12-month Euribor (the European equivalent in euros to LIBOR in eurodollars and SHIBOR in renminbi) is below the MRO. It is the same violation that we see in US$ repo, where the collateralized policy rate in euros is “somehow” steadily above now all the unsecured maturities.

Not only that, Eonia, the overnight rate in euros equivalent to federal funds (or O/N SHIBOR), is actually above the corresponding unsecured Euribor rates out to 1-month. And by “above” what we mean is less negative, as if that could serve as some kind of meaningful answer or distinction.

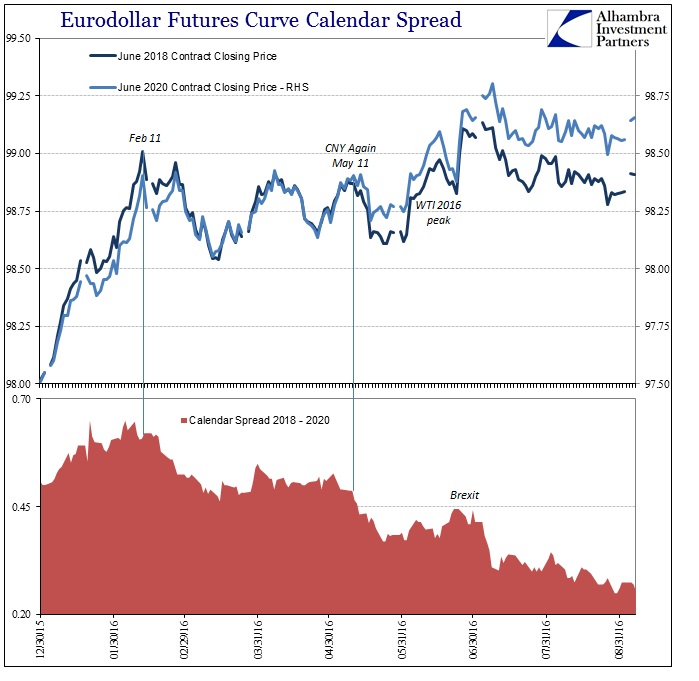

In eurodollar futures trading, the eurodollar money curve continues to compress in such a steady manner that it is, frankly, unnerving. Though the June 2018 contract, for example, “has” to respect possible changes in Federal Reserve policy, it has done so by trading only slightly lower in price (meaning a slightly higher probability for ever so slightly higher future interest rates). The June 2020 contract, however, has traded even less so in this manner, leaving this highly important calendar spread section to shrivel that much more, compressed down to now an unthinkable 25 – 26 bps (a highly bearish interpretation for the time value of money as the economic consequences of money markets as they are right now).

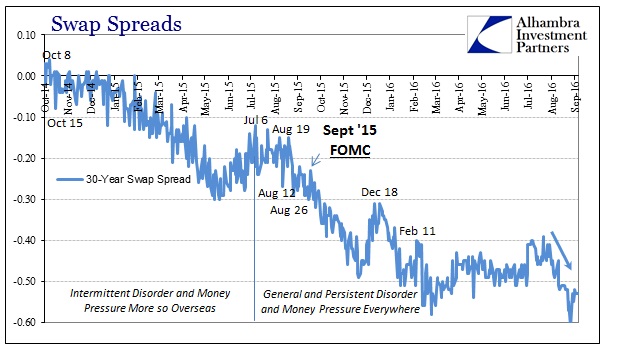

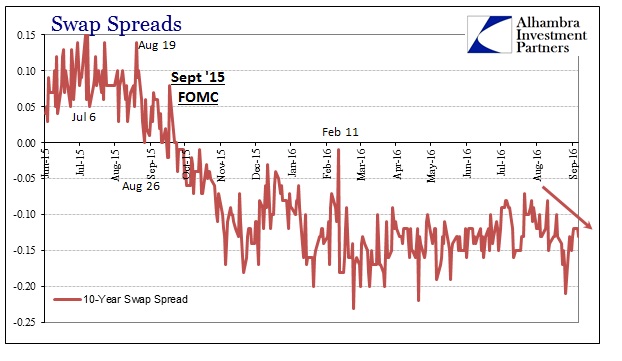

And while CNY and SHIBOR swap places, interest rate swaps in dollars once more suggest perhaps more than a little monetary difficulty in the same hidden or opaque segments of the “dollar” markets that are never accounted for.

The deeper negative compression in the 30-year spread is particularly concerning given that it was the 30s that signaled the first real warning about last year’s events including and especially related to China. While it obviously isn’t enough to make the same suggestion about what might be happening in September 2016, there is at least one part of all this worldly muddle that we know for sure: none of it has anything to do with 2a7 money market reform.

Whether it is SHIBOR as now different from CNY, or Euribor somehow staying below Eonia, or even primary dealers in both UST’s as well as UK gilts that refuse to part with their inventory, the common theme in all of it is balance sheet capacity, the actual global money supply. That is why swap spreads are so compelling especially already negative and especially when they might become more so. Is it mere coincidence that the PBOC has completely rearranged its liquidity priorities just after 30-year swap spreads in “dollars” sink to new lows? Swap spreads are a more direct if still implicit indication of balance sheet capacity – or really incapacity. And we should not forget that when the 30s first turned negative last year, that, too, was written off as nothing concerning, just a plethora of cheerful corporate issuance.

When swap spreads turned negative again in early 2010, for example, media stories of corporate fixed income volume filled the space to assure that all was still quite well; obviously it wasn’t given what happened not long after. Loyally replaying that very same tendency, earlier this year we received the same bland message, “ignore the turn in swaps because it’s just fixed income being more normal.”

Any actual catalog of swap spreads, especially since the “dollar” began “rising”, shows that to be utterly false. There is nothing at all benign about negative spreads, especially now, after August 24, where they are still sinking in every maturity.

Money markets are a mess because bank balance sheets are a mess, and all that has turned the combination of illiquidity and central bank interference into a swirling mass of growing disorder that has absolutely nothing to do with money market reform. The Chinese are not rearranging their operative monetary RMB conditions to allow potentially more devastating internal tightening because US money market funds might be switching out of the prime format as NAV’s get set to float. They are doing so because balance sheet capacity is highly and hugely constrained (globally) as a result of a great many negative factors – but mostly the fact that global monetary policy has been so thoroughly disproved and debunked as to leave the global economy in depression that it renders to banks only great risk and no possible reward for undertaking money dealing activities in all their disparate and often-confusing dimensions across all currency denominations.

What I wrote last September about the perils of ignoring swap spreads applies again this September; the mainstream has just swapped 2a7 reform for “corporate bond issuance” as the benign but ultimately futile excuse:

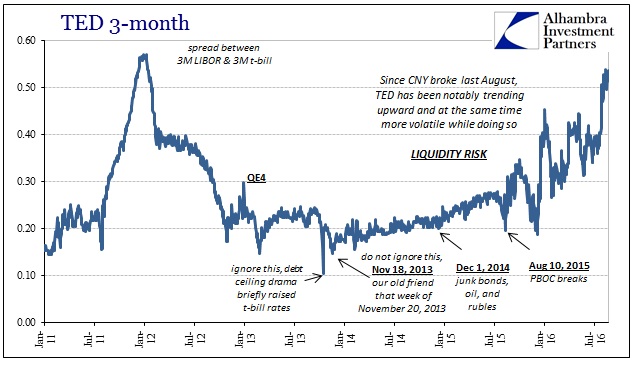

Heading toward the quarter end, this should be quite concerning rather than, like LIBOR, ignored or rationalized yet again as if it were welcome and expected.

In other words, SSDD.

Stay In Touch