Throughout Milton Friedman’s (and Anna Schwartz) seminal book A Monetary History he tries to make the case that suspension of convertibility would have alleviated much of the suffering of the Great Depression. It had in the past worked in that sort of capacity, choking off the suffering of systemic runs just enough so that emotion could die down and cooler heads prevail. He was particularly harsh for when suspension was, in fact, used – afterward.

The term suspension of payments, widely applied to those earlier episodes, is a misnomer. Only one class of payments was suspended, the conversion of deposits into currency, and this class was suspended in order to permit the maintenance of other classes of payments. The term suspension of payments is apt solely for the 1933 episode, which did indeed involve the suspension of all payments and all the usual activities by the banking system. Deposits of every kind in banks became unavailable to depositors. Suspension occurred after, rather than before, liquidity pressures had produced a wave of bank failures without precedent. And far from preventing further bank failures, it brought additional bank failures in its train. More than 5,000 banks still in operation when the holiday was declared did not reopen their doors when it ended, and of these, over 2,000 never did thereafter. The “cure” came close to being worse than the disease.

It was this loss of banking capacity that through even the new monetary system of the New Deal, stripped of gold money, would regret for the rest of the decade and beyond. Though there seemed to be recovery at the time, as the bond market showed then, as it does now, it wasn’t actually one.

This is a problem that has plagued banking for as long as there have been banks. Emotion is a part of money, but economists felt it necessary to deprive people of property rights so that they might be in better position to save “good” banks from suffering the same fate as “bad” banks. That is what bank holidays and suspension of convertibility meant; to allow less pressing circumstances by which to sort out which bank actually belonged to which category. The systemic cost of getting it wrong is enormous.

But as Friedman himself describes above, placing the balance into the hands of government officials is itself no guarantee, either. It is that fact which has become the central focus of our own time, where economists were handed all the power they sought and we ended up with the same circumstances anyway. The only difference between the 1930’s and the 2010’s is the size of the crashes which preceded their depressions. And unlike the previous one, this one actually happened in the very place which was supposed to prevent just these circumstances. There just is no way to describe in words the cosmic irony.

Clearly, what counted as money during the Great Crash after 1929 is nothing like what counts as money today. There were then as now Federal Reserve Notes but only in denominations to as low as $5; the smaller cash bills were US Treasury silver certificates, a legacy of William Jennings Bryan agitation that actually lasted into the 1960’s. The primary difference of those compared to what we find today is convertibility. Cash and currency at that time was properly understood as a derivative claim on money, but not just money as gold but money as personal property. There is a huge difference.

A bank that holds property is bound by the terms of constructive bailment; the same kind of arrangement as when you hand the keys for your automobile to a valet. Your car does not cease to belong to you, it is only transferred into the temporary custody of the valet company who has responsibilities for its safe keeping. Should the valet business declare bankruptcy while you attend whatever activity that brought you into this arrangement, they cannot sell your car to satisfy their creditors – by all property rights it remains your vehicle no matter what.

From that perspective, we are forced to think about “deposit” accounts as they are today; there is nothing like this framework, though depositors are offered what sounds like similar guarantees (including the FDIC). You don’t notice it because it doesn’t seem a particularly troublesome issue, but convertibility defines everything. And the lack of convertibility, because there is no money anymore, is where we run into all this trouble:

So the great distinction in money vs. currency is really the emphasis placed upon the bank rather than the individual. In MF Global under property law, the bank doesn’t really much matter as its responsibilities are clearly defined to return all property in a timely fashion. In MF Global under financial law, everything is entangled in the bank’s own business and thus the bank is paramount over everything else.

When some people look at the Federal Reserve Notes they might be holding, they likely notice that there isn’t anything substantially different from one denomination to the next; all that changes is the number (and some other artistry) stamped upon its face and obverse. This is the fiat they more often appreciate, when in fact it is more trivialized. Again, convertibility defines everything, where the cash you hold is not truly in your possession. And the bank account balance you use for everything is but a virtual claim on nothing. But in that arrangement the only thing that matters is the bank; under convertibility, what truly matters are your rights as a property owner which places the bank subservient to your autonomy.

It is in many ways the parallel position as the Facebook “conundrum” which has become more of a public issue lately. In other words, many people are confused by the arrangement where Facebook is often thought little responsive to the people who use its service. This anger is misguided if not completely misdirected; you are not Facebook’s customer, you are its product. The same is true of banking and modern money; you are not the bank’s customer, you are but one liability scheme among many competing and often overruling forms.

I wrote earlier this year about the US Treasury Department’s curious choice with which to “sell” its commemorative $1 coins. Coins of this denomination have proved quite unpopular as fiat, so there was bound to be some fuss so as to justify their minting. What they decided was almost an insult:

Somehow I came to find in my possession a $1 coin with William Henry Harrison’s image stamped on its front. While there is some fixation on the $20 bill, specifically the presidential image on that one, Harrison seems at least innocuous compared to the others that have achieved and delivered far more for their time in that office. The answer from the US mint was not a celebration of Harrison as it was a series on US Presidents. The 2016 versions struck for the $1 coin will be the last in the array, featuring Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Reagan…

Harrison’s portrait, and really any of the others, isn’t even the most striking aspect of the program, as the mint’s website explains. “The size, weight and metal composition of the Presidential $1 Coins are identical to that of the Native American $1 Coins.” The metal assuredly isn’t gold, which means nobody really cares that the coins are identical chemical elements and the same fixed quantity. The number of people who can even recall that being a relevant factor has to be such a dwindled proportion as to be irrelevant (the coin’s composition, not the people). It can only be “tradition.”

When given the exclusive power of the printing press, the Federal Reserve assured us that there would be no more depression; that it could live up to the mistakes of the past where the people were, as economists still believe, unworthy of the power over money. The Institution (capital “I”) of the Federal Reserve would take that great responsibility on our behalf and wield it with far better results. Some Fed officials still actually make this claim despite debacle after debacle with QE, ZIRP, now NIRP and even “yield curve targeting” that is perhaps the most absurd of them all (economists who believe they can fool the economy into blindly accepting a “steeper” curve from artificial means as if it were the result of an actual positive outlook).

And even through all those failures, where are they intended? Their target was never you and me, at least not directly, but banks, banks, and banks. If hard money still existed in the form of $1 coins whose metal content actually mattered as property, the Fed wouldn’t have been able to experiment time and again with increasingly ridiculous theories – because at most they could only have printed currency whose acceptance would have mattered as a consequence of (perceptions of) convertibility. Power to the people.

Instead, as I wrote in January:

This upside down nature even “works” in symmetrical fashion, which is really the whole point here. In other words, “not money” was exploding in asset bubbles and asset inflation while “money” did nothing, but on this side of 2008 (really August 9, 2007) “money” is exploding and “not money”, though we can’t know for sure because nobody in position to do so is interested enough to check, is disappearing at an increasingly worrisome rate. The world, world markets, and especially the world economy are once again following “not money” and do nothing like what all these bank “reserves” propose. All that has changed is the direction, leaving, again, breathtaking symmetry.

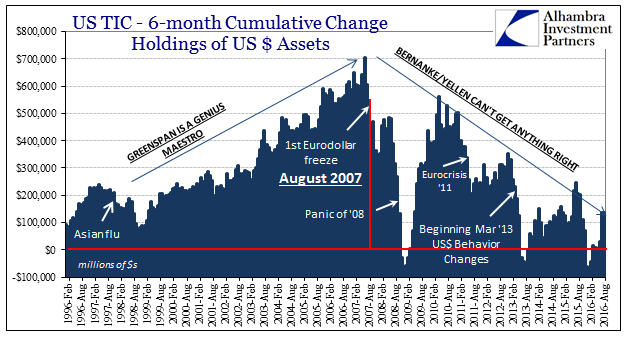

We see this clearly in several “dollar” proxies where before August 2007 the Federal Reserve was thought populated by none but geniuses, and after August 2007 widely believed now left to the considerable folly of fumbling idiots. What really happened was that banks mattered so much they became all that mattered, as if a computer system that becomes at some point self-aware and exclusively self-interested. This where the dollar stopped being the dollar and became the “dollar.” Convertibility kept a lid on not just quantity expansion but also quality expansion where money can today no longer be defined. As I write so often, the eurodollar is not now nor has been since its earliest years a thing like dollars are a thing. They are bank liabilities of often unbelievable complexity and they are all that matters.

That happened because what was left as the only constraining factor for banks was the undisciplined focus or attention of economists. While they were sleeping on the job, perfectly content with how they would handle 1929 should it recur, the world of banking became almost totally recognizable to them (or anyone, including global bankers) precisely because people never got a say in the matter. Most people, it should be pointed out, were perfectly content with this arrangement, when it seemed to everyone’s collective benefit. Now, not so much; but it progressed to the point where a layperson not only can’t define what is wrong, though they are sure there is “something” really off, they are very likely to have never heard of the eurodollar at all. From monetary sovereign to passive ignorance, this trajectory of the dollar transforming to “dollar” explains a great deal.

For whatever it is that comes next, it should include some kind of arrangement that either reaffirms or replicates convertibility, not as an element of “tradition” but rather why that tradition kept hold for centuries. Hard money defines the balance of financialism to where it is skewed in favor of the people (and market forces) rather than economists who have proven themselves many times over nothing more than political creatures who would rather maintain themselves with their current political standing than actually allow a recovery. Convertibility doesn’t give them that option so easily; to stand so clearly in the way of needed recovery year after year until not one decade is lost but multiples of them. Given the choice, I bet most people would take the prospective messiness of truly free market money (that actually is money) that delivers actual growth over perhaps decades of none. We can more easily live with the occasional depression, but we cannot with the one that doesn’t end.

The end of convertibility achieved little that couldn’t have been under the prior monetary schematic, but now has invented a new and likely more disruptive way in which to fail. If the 1930’s were defined by their loss of monetary capacity, the 2010’s are, again, defined similarly except this time nobody knows what in the hell is going on – including banks. Monetary reform needs to be defined surrounding property rights so that banks are no longer the central piece for economic activity, and that when things do go wrong, as they inevitably will, it is not left to one “solution” that never solves a single thing.

Capitalism often means different things to different people, but the core properties always must include property rights and competition. Without convertibility, we are left without property rights and increasingly no competition. The results are not capitalism and they have produced circumstances that reflect this fact.

Demanding that currency be backed by something, anything tangible is to understand the consequences of what will happen when it isn’t. Most of the time, that usually has led to fears of hyperinflation or “overprinting” when in the modern sense it has been altogether different and I would argue much worse. In a hyperinflationary collapse there is at least an end; a catastrophic one that nobody should wish for, but a reset nonetheless from which it all begins anew. Now, we are left no choice but to wait for economists and banks, neither of whom has suffered much for the circumstances. Japan lies in that direction, at a quarter-century and still waiting for resolution.

The New Deal said that people couldn’t be trusted with money; the next New Deal, the one that goes back toward capitalism, must make plain that economists and authorities can’t be trusted, either. There must be at least checks and balances, and property rights are those. We cannot continue to be solely concerned about a crash or recession as if they are the only something to fear. And even if that was the objective reality of it all, it still doesn’t justify deprivation of rights because economists have proved they aren’t any better; on their way to showing that they were, in fact, the inferior choice all along.

Stay In Touch