When I first started some years ago, the guy I worked for told me to prepare myself because this business is so often just stupid. It does make sense given the high stakes and pressure, where everybody is literally trying to outsmart everybody else every minute of every day. And those kinds of conditions, variable as they are, lead to circumstances like those last night. Stock futures indicated something almost as bad as August 24 last year on nothing more than a knee-jerk reaction to the election.

It wasn’t even the election itself, however, but changes in perceptions, and really perceptions about perceptions. The night started with Clinton assured of victory according to all the “right” people and places. The New York Times projection model, for example had given the D ticket an 85% chance of victory. But as polls closed and states came in with their tallies, it swung sharply in the space of about an hour; models and perceptions. By the end of the night, what was supposed to be nearly impossible had actually happened (proving yet again the unsuitability of statistical analysis for complex systems where variables more often than not cannot be defined, let alone modeled).

I don’t think Wall Street actually thought it was as bad as all that, after all Hillary was booed by the NYSE Floor during her concession speech this morning. What I believe happened was that the “market” tried to outsmart itself by figuring what everyone else would figure about a Trump victory. In other words, traders clearly believed that the rest of the world believed the “impossible” result was catastrophic; that was the mainstream narrative all along. Stock futures dumped.

By morning, however, traders came into business and those panicked, emotionally-placed sell orders just never materialized. It was a tempest in a teapot, and exclusively an after-hours one. Trading today has been remarkably different than all that because there is a side of Trump that is appealing to more than just voters – and it really doesn’t have much to do with him.

After cautioning about making too much about what markets think others think markets think, I am going to do just that. There is a context to all of this in finance as well as economy that in my view has become quite clear. Voters were motivated by economy, another “impossibility” as determined by the IYI’s. They moved in this direction of actualized resentment over time, as the recovery that was supposed to be is now judged as never was or will be. Markets have made the same progression in parallel.

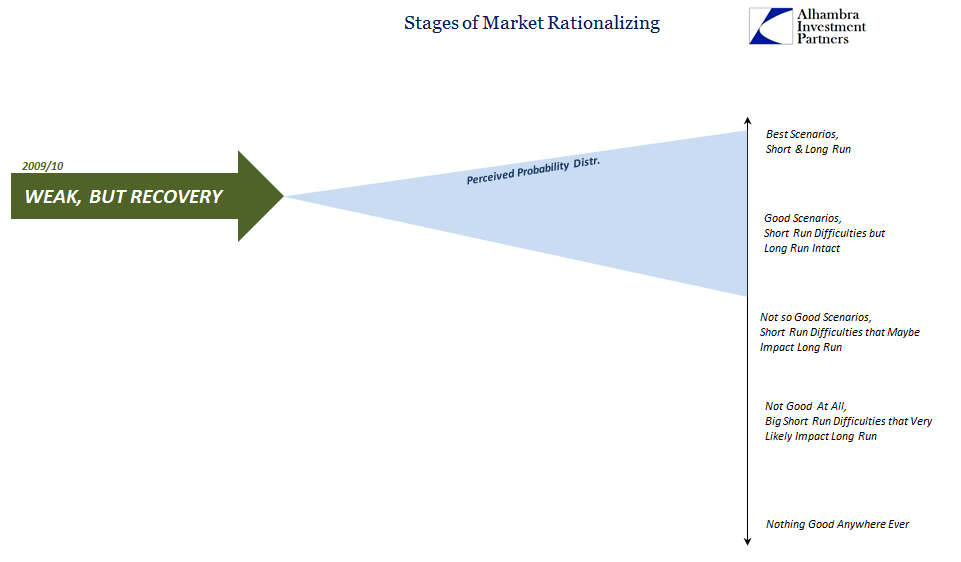

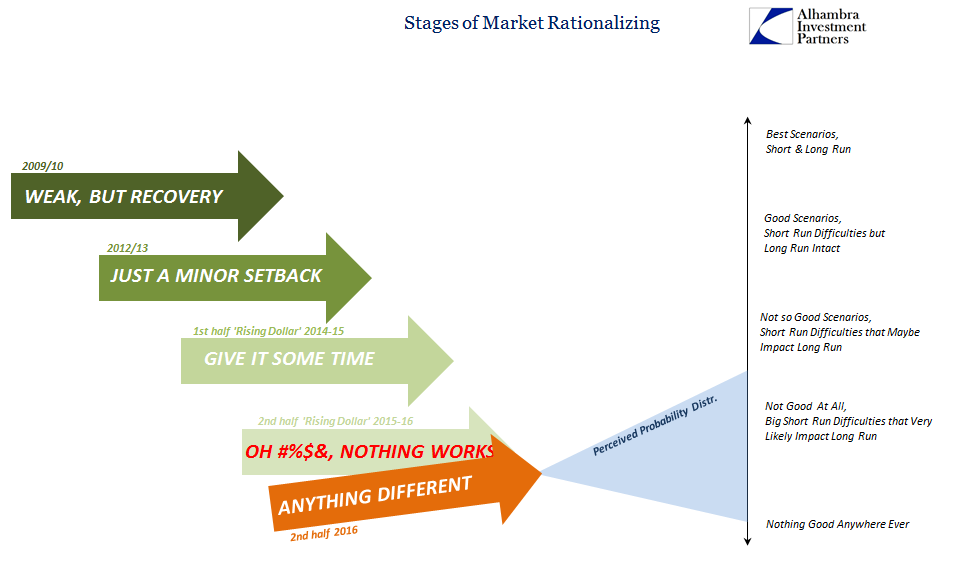

For the rest of this piece I will refer to bond and funding markets as “markets”, leaving stocks as not entirely different but needing some adjustment and recalibration to my stylized model. Going back in time, the early stages after the Great “Recession” were already off by historical standards, but by and large markets perceived that as perhaps a limited circumstance tied to the size of the contraction that had just ended. Perceptions about the long run, especially with so much “accommodation”, “stimulus” of all kinds, and global coordination remained largely undisturbed. The forward perceived probability distribution was thus highly positive, believing that whatever downside risks were minimal and at worst contained in the short run where Ben Bernanke with great skill and courage would take care of them.

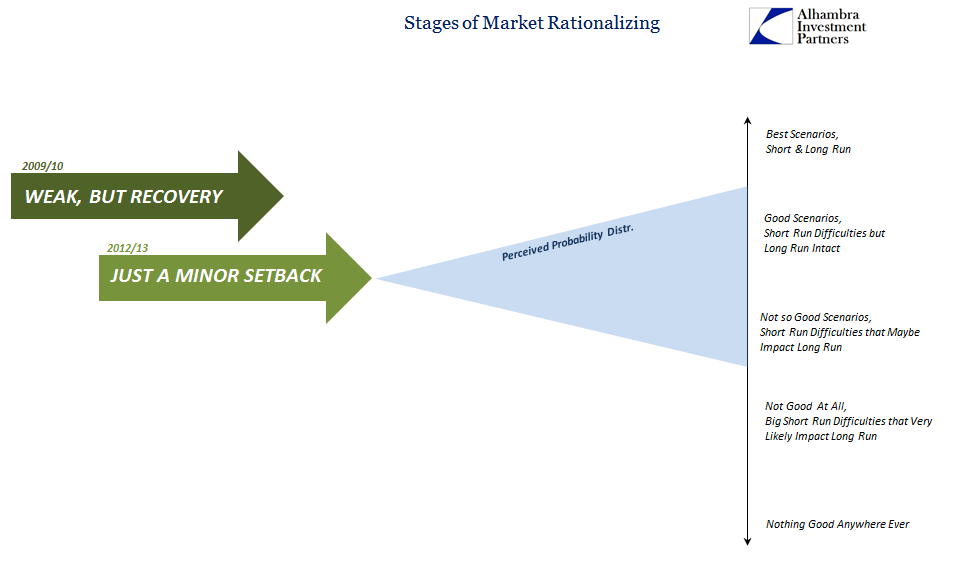

It just didn’t quite progress as it “should” have from there, especially starting with the huge disruption that was 2011. Each time these monetary events intruded, it forced markets to outwardly rationalize why, but also become more realistic about what it could mean if being honest about it. In between hearing economists and policymakers say it wasn’t possible, these markets more and more contemplated that it might be at some point.

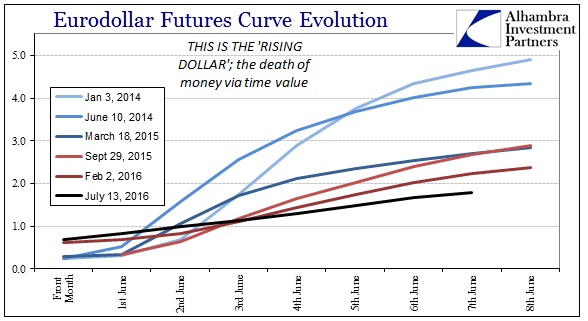

By the end of 2013, markets were already considering almost a split probability range that encompassed some good and some bad, but skewing more toward the downside in both the short and long run perceptions. At that time, UST investors as well as those in eurodollars and FX had begun to contemplate what more short run disruption (economic as well as market) might mean for a system that hadn’t yet actually healed from the Great “Recession.” The trajectory of eurodollar futures were that exactly that junction, where funding markets were viewing renewed short run turmoil as almost certainly damaging long run prospects.

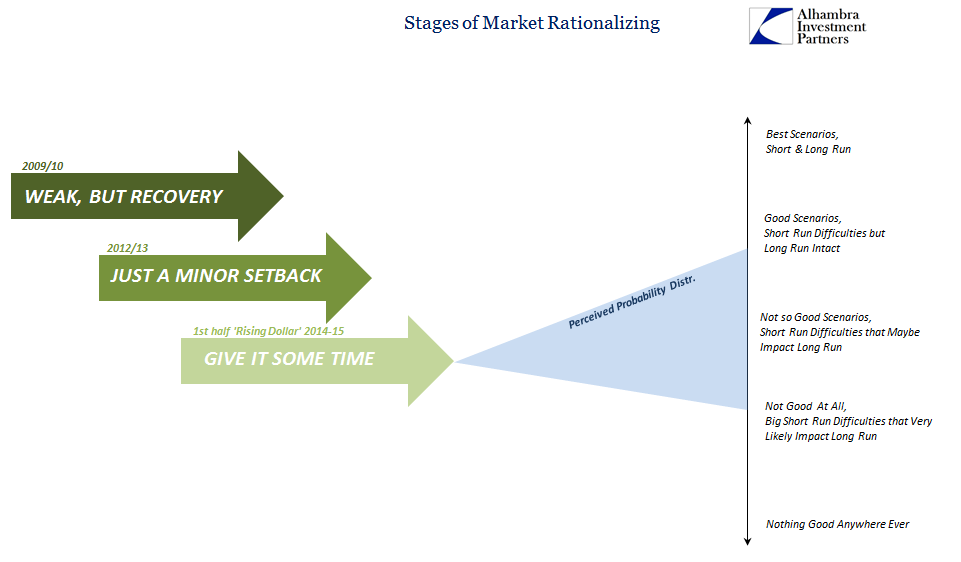

That is why the “global turmoil” of 2015 was so devastating across the board; markets were receiving confirmation that all its fears were not just small probabilities in a slightly pessimistic distribution, they were the base case. What was once thought a “tail risk” under Bernanke’s watchful eye had been turned to the best case as all but guaranteed by his and Janet Yellen’s more realistically assessed incompetence.

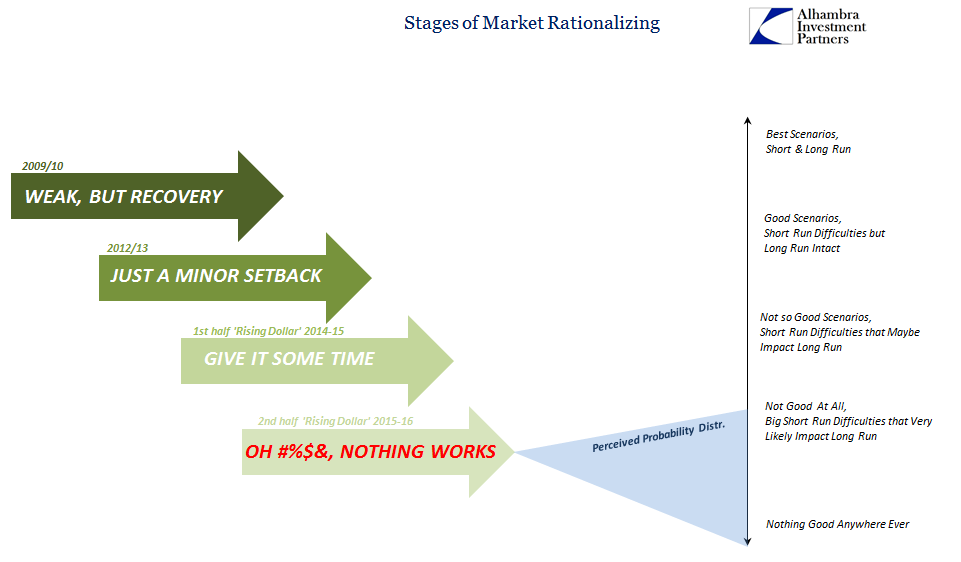

It meant completely repudiating QE and all the rest of the monetary “tools” that were once accepted on faith alone. If the first stages of the “recovery” were bid based on trust in Ben Bernanke, 2015 and the start of 2016 left markets contemplating a world that was bad in the short run, undoubtedly creating further havoc and distress for the long run, and no longer any belief that central bankers were able to do anything about it. The worst of the worst; a downward spiral without any way to pull out of it.

By this summer, that is exactly what these markets were trading for; probability distributions that were almost totally devoid of any positivity whatsoever. Nominal rates crashed and curves all over the world collapsed. Central bankers noticed, and for the first time started to admit, softly, that past monetary efforts were, in fact, ineffective.

From that sprang hope, though hope is undoubtedly too strong a word. Central bankers started to talk differently in a way we haven’t seen before. Not only talk, but in some cases action. There are any number of indications that central banks have been more attuned to the “dollar” this year where last year they seemed almost complacent about it (fitting, actually, there dismissive rhetoric). The market has noticed.

Further, in what started with the BoJ and its helicopter, there were clear signals that authorities were no longer attached to just the same old QE’s anymore. They might be willing to try something else, maybe even anything else. To markets starved of any positivity, different is hope. When nothing that was tried before works, even the apparent willingness to stop doing the same is a measure of optimism.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that markets are now back on board like they once were with QE’s. It only means that from the dark days of summer, the potential of different is at least enough to more positively skew deeply negative future perceptions; where the world was damned to nothing but recessionary weakness for all eternity, now there might be some small hope (again, too strong of a word) that central bankers in doing something other than QE might even accidentally get something right.

These shifting perceptions are not driven by just thoughts on future monetary policy; any significant change is at this point a slight boost in the probability distribution because it adds just a bit more to the probability of discovering something else that wasn’t available before “global turmoil.” Donald Trump fits that description even though we really have no idea what a Trump administration might actually mean. We might in principle have some rough outlines from which to begin considerations and analysis, but at this point his Presidency is in the same category as post-QE monetary policies – a blank slate whose best qualities are that it isn’t already tied to past failures. It might still end in failure, and markets seem to still consider that the likely case, but at least there is a chance however small.

I would even add Brexit to that hope in at least wider reconsideration about what that might actually mean apart from aggravating all the “right” people (which is now a virtue). In the end, however, markets are likely to be disappointed on all fronts unless Trump surprises with some actually useful reform instincts like those I suggested this morning. In terms of whatever new forms of monetary policies this change might lead to they aren’t likely to be any more effective because in reality it really is just more of the same because that is all economists and central bankers have. For now, these markets appear willing to cut them some slack at least until they are pressed into providing actual details and spoiling the current small infatuation with the undefined.

Markets are bidding hope, but not really hope just no longer ubiquitous despair. Everything is relative.

Stay In Touch