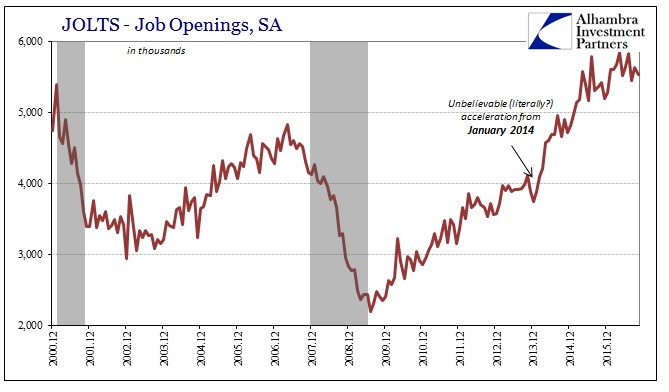

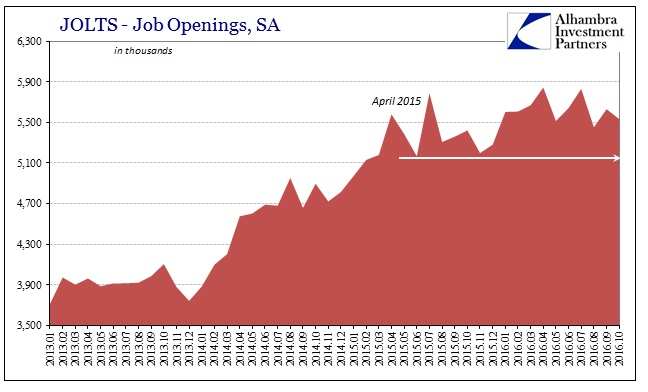

The JOLTS survey continues to show a lack of acceleration in the labor market. Even previously robust Job Openings estimates have plateaued. After surging throughout 2014 and into the middle of 2015, the level of estimated job openings has been more or less the same since. That might indicate the labor market reaching saturation, or it might suggest, as all the rest of the labor data apart from the unemployment rate, some degree of significant slowing.

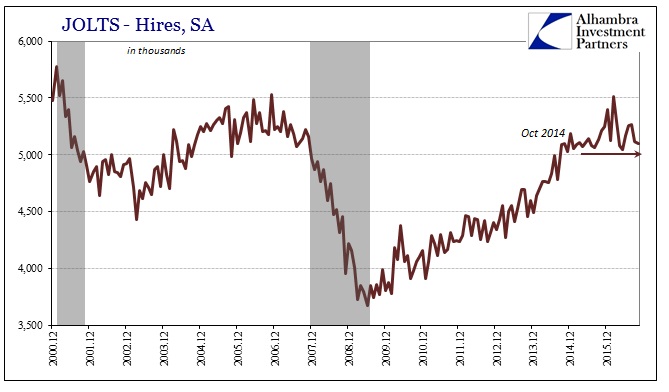

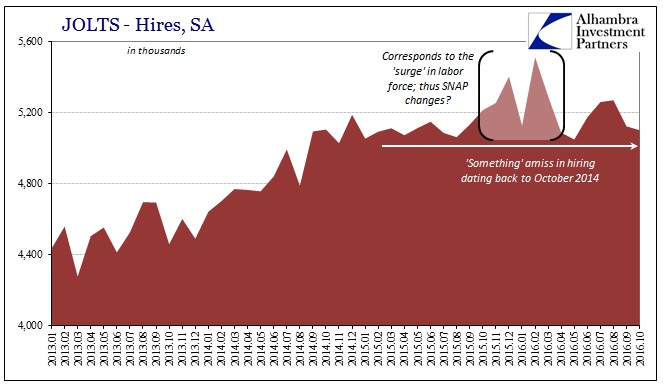

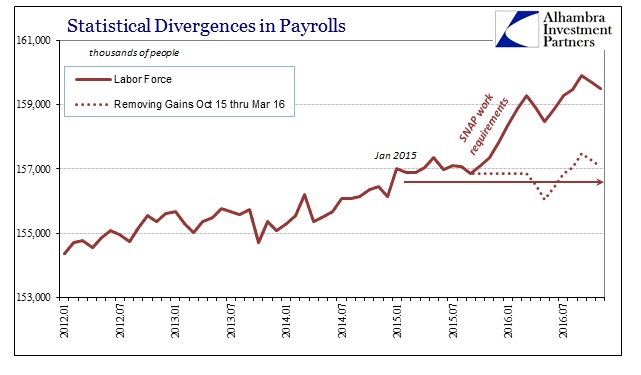

The Hires component of JOLTS seems to further indicate the latter interpretation. In this subset, the rate of hiring ceased expansion all the way back in late 2014, and aside from the temporary differences due in all likelihood to SNAP work requirements changes that showed up in the Household Survey (CPS), the estimated hiring rate seems to be stuck at around 5 to 5.2 million (SA). On a year-over-year basis, the rate of Hires in November 2016 was 2.2% less than November 2015, the largest such annual decline since March 2013. It was the third time in the past seven months that Hires are less this year than last.

The 6-month average change is now nearly zero, the lowest average growth in estimated hiring activity since 2009. These figures largely match the rest of the BLS data, again apart from the unemployment rate, with one key exception – 2014.

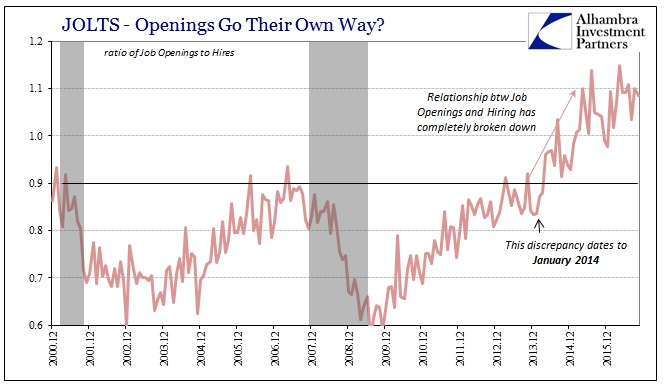

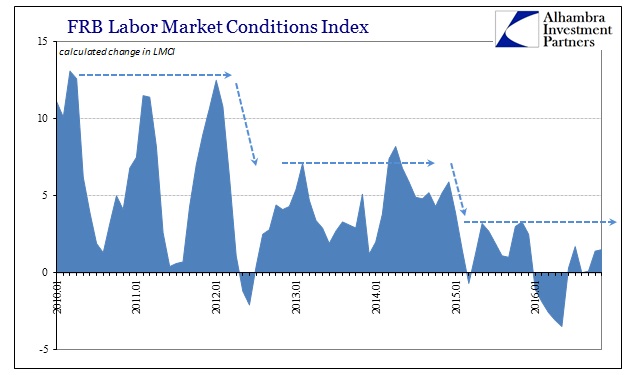

The acceleration in both Hires and Job Openings, though mostly the latter, is not replicated anywhere except the Establishment Survey. That is unsurprising since the JOLTS data is benchmarked directly to the CES, meaning that JOLTS figures cannot corroborate the Establishment Survey and vice versa because they are linked together. The Federal Reserve’s LMCI, by contrast, presented a much more muted labor market in 2014 especially as compared to the months and years of near recovery immediately after the Great “Recession” but before the 2012 slowdown.

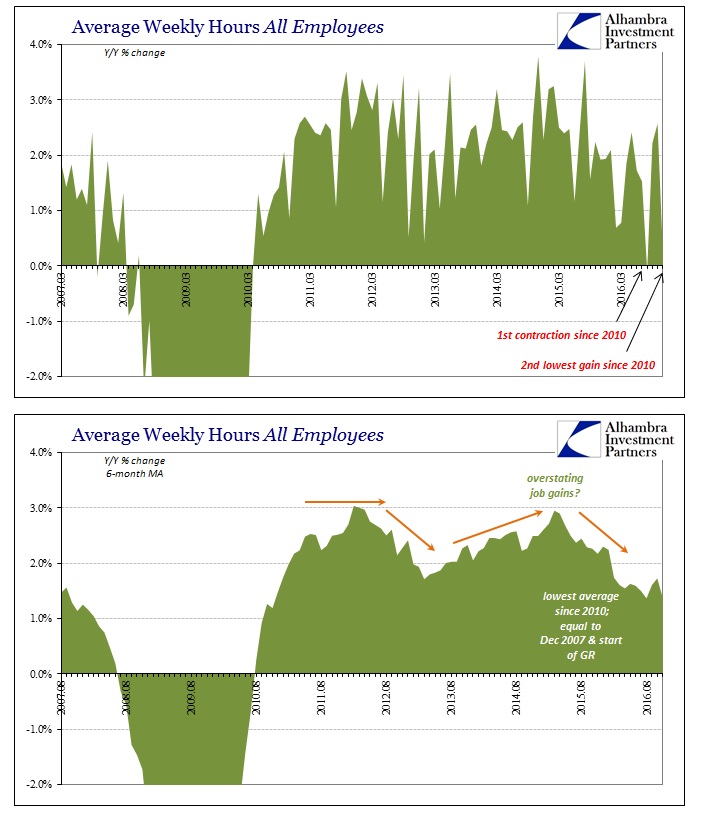

What is consistent across all these labor statistics is that the economy clearly slowed starting and before 2015, which has only continued throughout 2016. What is more debatable is from what level that slowing occurred, though in many ways this late in the process it only matters for accountability as it might pertain to misleading mainstream interpretations of that time. In other words, whether or not the labor market was truly the “best jobs market in decades” had no impact on the economy that was concurrent to it; it became weaker regardless of the labor stats.

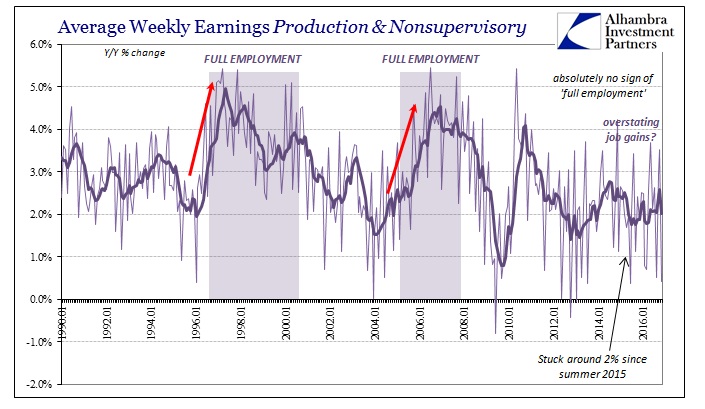

However, there is still public interest in reconciling why policymakers in particular were so attached to the one version, the wrong version as it turned out, denying the very real prospects of the other that were less charitable toward economic interpretations even in 2014 but especially 2015. After all, it was the constant refrain in the mainstream that any weakness of that time would be “transitory” if not irrelevant primarily because of the conventional view of the Establishment Survey, Job Openings, and the Unemployment rate, which were contemporarily questionable since they were unconfirmed by a good catalog of other data including Hires, wages, and spending that should have been consistent.

Those same policymakers are again using employment data as “evidence” of an economy and recovery that even fewer labor statistics suggest now than last year. Monetary policy can therefore be said to be totally divorced from actual data, the unemployment rate and its troubling denominator the lone, isolated exception.

Stay In Touch