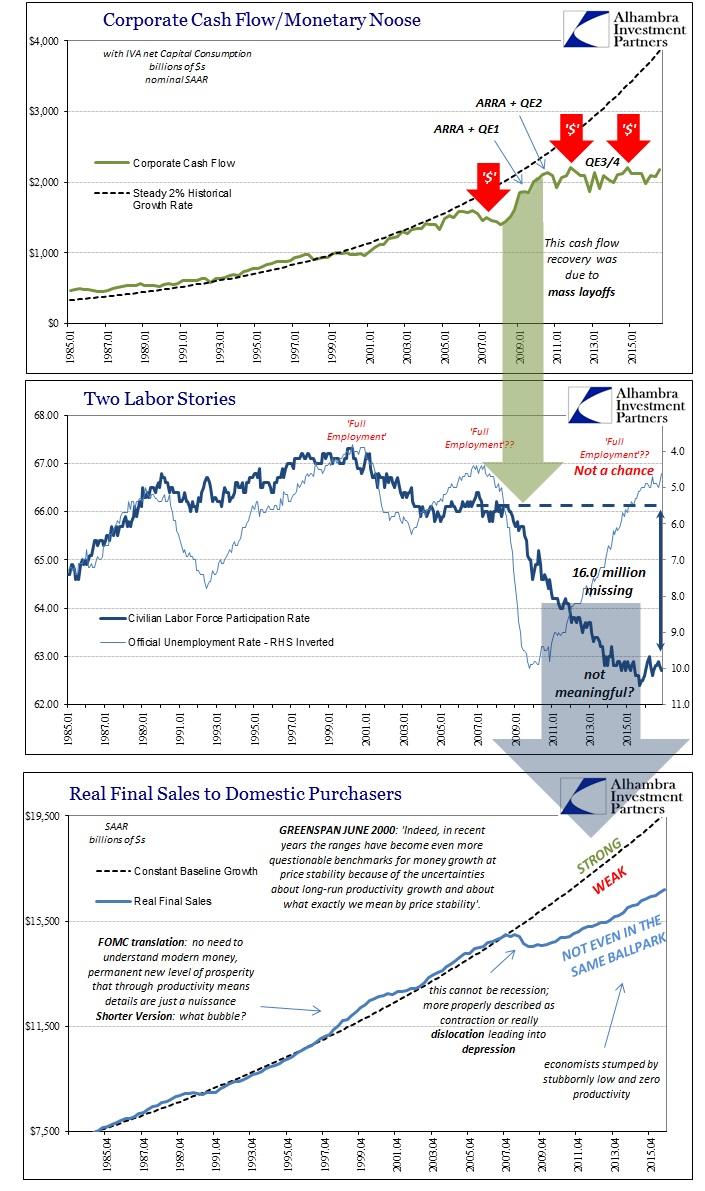

There is a distinction between actual, meaningful growth and plain positive numbers. Recession everyone can agree on, as nearly every economic account (but not all) finds itself with a negative sign. Because of the binary model that the mainstream associates with all economic conditions, the absence of contraction is conflated with meaningful growth, even where the statistics are nothing like it.

Because of this, positive numbers are the worst case scenario. Recession is a cyclical process which has a predetermined end – inevitable recovery. Though it might be bad to very bad for a time, we know that when the negatives turn positive the economy will resume its prior place after a relatively short adjustment.

The current economy is nothing like recovery; nothing. But it is and has been full of positive numbers which actually hinder the recovery process. They do so because they cloud the issue as to whether there is anything wrong, let alone anything so serious as to indicate an economy beyond the business cycle. Economists can plausibly claim that there is growth, even though the fruits of actual growth remain viscerally absent from day-to-day life.

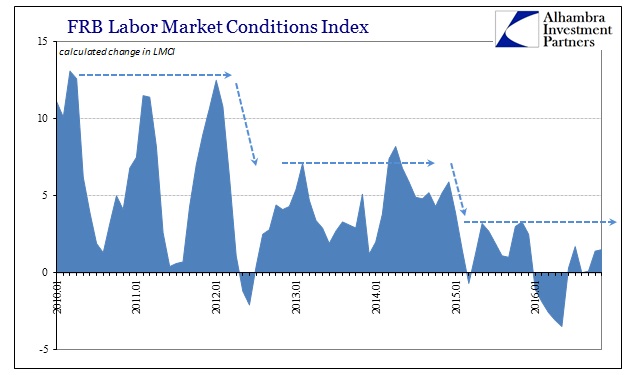

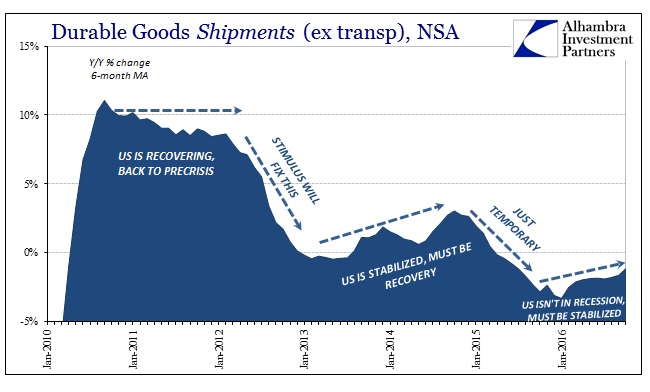

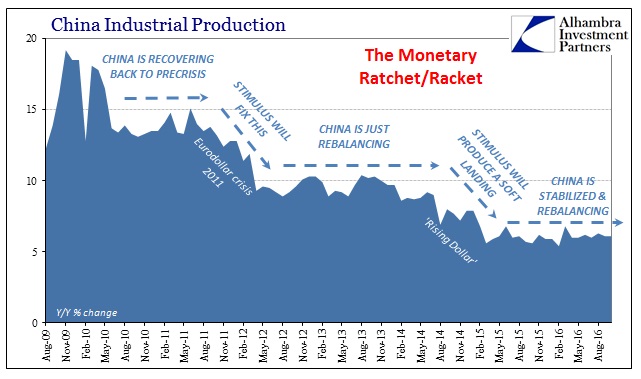

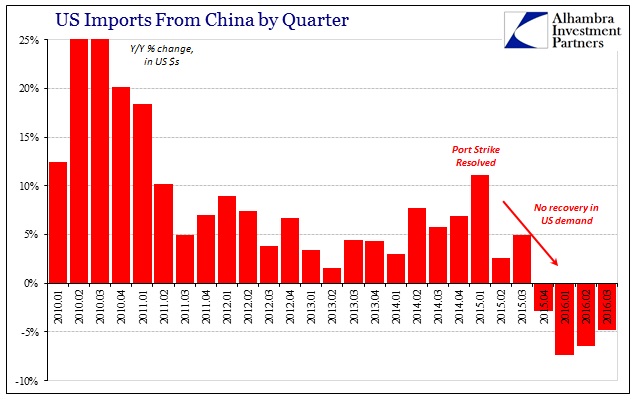

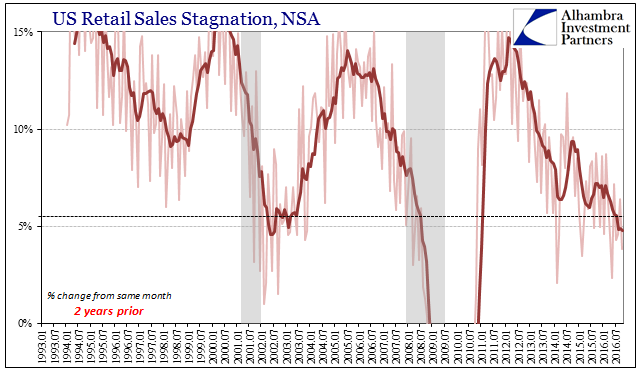

The ambiguity of positive numbers is their biggest danger. They bolster the mistaken to keep making the same mistakes because whatever had been done didn’t lead to unambiguous contraction. That was the difference about this “rising dollar” version as opposed to the phase immediately after the 2012 slowdown. Starting in late 2014, negative signs began to appear and not just in the US. Tied mostly to manufacturing and trade, steady contraction turned the tide of opinion and even expectation toward realizing the difference between positive numbers and actual recovery.

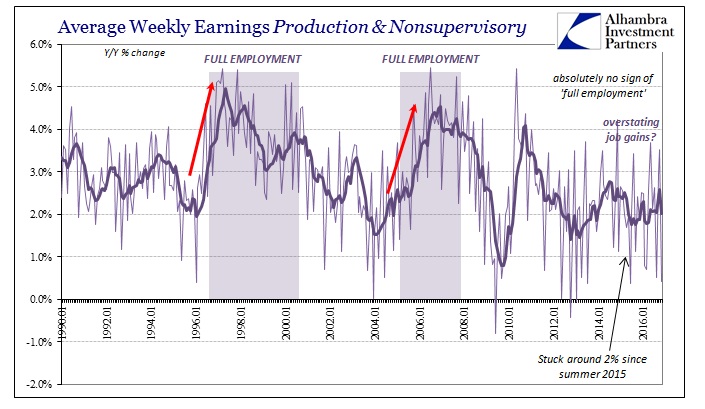

It was only positive numbers upon which policymakers and economists (redundant) predicated their assertions about “full employment” and what that was supposed to mean for the full economy entering 2015. Because those positive numbers in 2014 became slightly more positive as compared to 2013 and 2012, that fog over interpretation fell in Janet Yellen’s favor. By the middle of 2015, however, such benefit of the doubt was removed when “global turmoil” revealed the distinctions so as to lay bare how the positive numbers of 2014 were not, in fact, indicative of meaningful growth.

As serious a revelation as all that was, we are right back into positive numbers all over again; though this time, in late 2016, there are still a great many negative signs that remain especially related to goods and trade. The unemployment rate has been unchanged throughout, which should only highlight its irrelevance, but it remains the leader of the positive number enthusiasts.

Primary among this cohort has been the media, championing at every possible turn all those plus signs though conspicuously stripped of relevant context which would show the difference. The election last month of Trump threatens to change the filter of this narrative, to the point of being ridiculous. To wit:

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump repeatedly described the U.S. economy as a hollowed-out disaster of high unemployment and stagnant growth.

But the latest numbers show the president-elect will in fact inherit a fairly robust economy with the lowest jobless rate in nearly a decade, record home and stock prices and a healthy growth rate.

That was written under the headline, I’m not making this up, Trump Inherits Obama Boom. I have little doubt that over the next few months there will be revisions to economic history along these lines. The last few years will be described in glowing terms further punctuated by irrelevant actions of the incompetent:

Trump instead will take office with an economy near full employment and wages and spending rising. The economy is in such strong shape that the Federal Reserve is likely to raise interest rates again later this month to try and cool things off.

What was the economy like the last time the Fed tried to “cool things off?” That is, essentially, my point; meaning that there truly isn’t any difference in the economy of late 2015, which hardly anyone outside the mainstream described as a “boom” (and more than a few inside of it who began to seriously reconsider a lot of economic narratives), and late 2016. This year was supposed to be night and day different from 2015, but in a great many ways it is worse (just ask the Chinese).

If the media is successful in persuading the public that it will have been Trump’s fault for the downtrodden economy of 2017, that would be yet another impediment to recovery because if the economy in 2017 is in trouble then it is the same as the economy of 2016, 2015, 2014…2007, etc. The only positive about that prospect is this past election, where on both sides there was a sizable rejection of the mainstream largely based on individual perceptions of the economy that were nothing like a “boom.”

What we are being told now is something like the establishment projecting that they have done their best and have achieved the best for us that was possible (demographics or something). We should simply be so grateful for those positive numbers.

One answer is anti-intellectualism — the very act of trying to figure out how to solve problems makes some see you as arrogant. 10/

— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) December 5, 2016

It’s hard to take all that seriously when these “intellectuals” spend so much time either telling us there is no problem (it’s a boom now!) or that only they can with enough time solve these minor deficiencies that don’t ever get solved and aren’t actually minor. To the layperson, they can vote Trump (or Sanders) as a rejection of the economic status quo, to which the status quo even after the election still replies, “but GDP was 3.1% last quarter.”

Positive numbers cloud these issues that with widespread display of the proper context would never have been so cloudy.

Stay In Touch