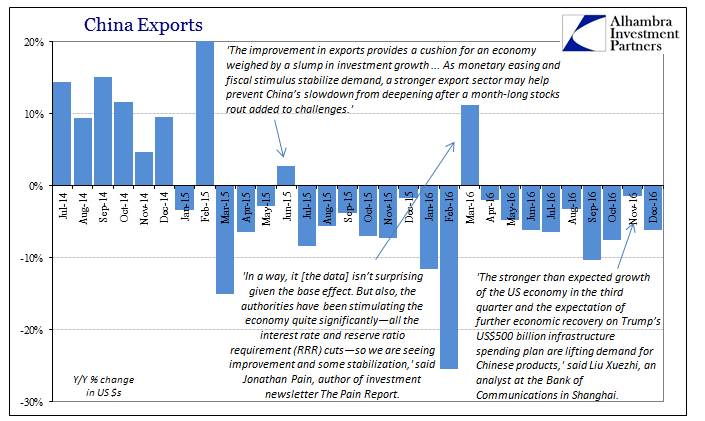

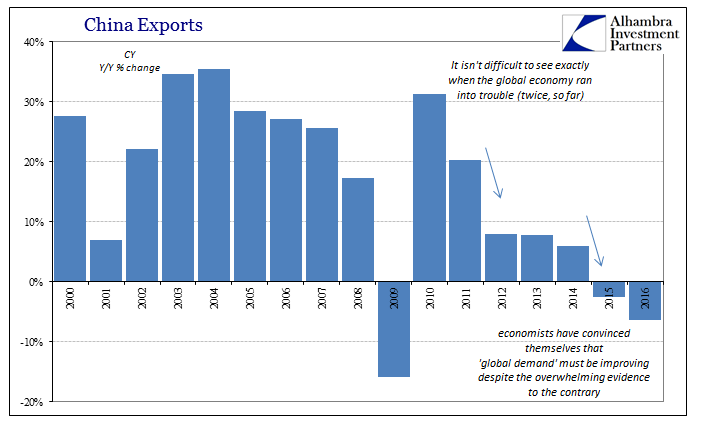

Chinese officials reported that exports fell 6.1% in December, following a downward revised 1.5% decline in November that was originally reported as a 0.1% gain. While the media talks about disappointment after it appeared Chinese exports might have been finally breaking out, and therefore global growth, December’s result simply continues the same pattern repeating over and over again. Over the summer, exports in August were first estimated to have been only -2.8% and an apparent improvement from June and July. Rather than continuing to progress in September, Chinese exports fell by more than 10%.

For the fourth quarter in total, exports were down by 5.1% from Q4 2015. That is seventh consecutive quarterly decline, five of which were more than 5%. The quarterly comparisons show far better the unchanged trend which has been obscured somewhat by monthly variability and more so the commentary surrounding it.

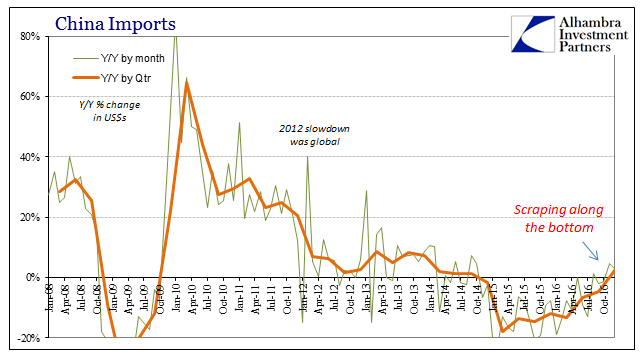

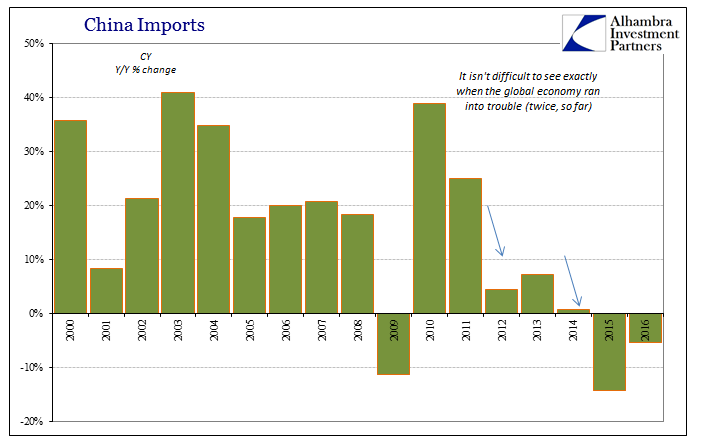

Chinese imports rose 3.1% year-over-year in December, a slight deceleration from November’s pace (which was also revised lower). Imports rose in the full quarter for the first time since Q3 2014. After collapsing in 2015, imports in 2016 seemed to have found a bottom. That doesn’t necessarily suggest that growth will return to normal or even that the internal Chinese economy has stabilized, only that it might not at the moment be deteriorating further.

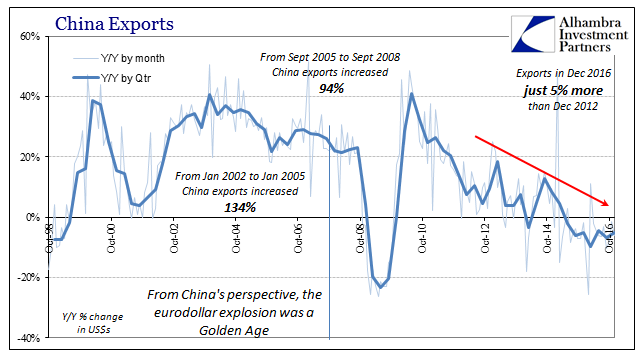

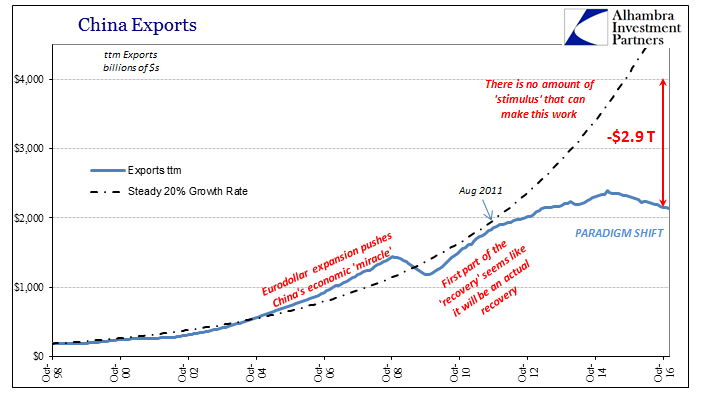

For the calendar year, exports were down more than 6%, appreciably worse than 2015. That is second straight year of declines, underscoring how the economic challenges in China, due to “dollars”, is both different and greater than those it faced during the Great “Recession.” In 2009, exports overall contracted by nearly 16% for the full year, but rebounded in 2010 by more than 30%. Exports following the eurodollar events in 2011 were never greater than 8% before contraction in 2015.

So while contraction is indicated only in 2015 and 2016, in reality, for China, the dramatic shift in the growth paradigm has completed its fifth full year and appears set to chart the same course still in 2017. Given that Chinese exports are a very good proxy for global “demand”, that is a hugely negative commentary on the global economy and its distinct lack of meaningful improvement in 2016.

Given that is very likely the case, it brings up the opportunity for where something is very likely to change – as of next Friday, as CNBC demonstrates:

China’s export growth will be limited if Trump unveils protectionist measures, Reuters quoted Chinese officials as saying on Friday. “China is the biggest loser in the anti-globalization trend,” officials noted.

In one sense, that is absolutely the case. As noted yesterday and again today, the Chinese have more to lose than practically anyone else in the populist revolt that is sweeping a great deal of the “developed” world. After all, no one place benefited more from the eurodollar’s fundamental support of globalization as much as China.

What should be pointed out, but isn’t, nor will it be, is that China’s export growth is already severely limited and has been, again, for five years in a row. For unnamed Chinese officials to complain about what Trump may or may not do is the epitome of disingenuous that I believe is about to become standard media procedure. So-called protectionist policies were not to blame for China’s exports declining 6% in 2016, the sputtering global paradigm of globalization under eurodollars was.

You can make the argument that dismantling trade agreements or implementing tariffs will make it worse than it already is, but that is a debate separate from this analysis. In other words, the Chinese are claiming that we need to go back to embracing globalization as it was quite like in 2006, and if we continue to do the same things eventually that will happen. That is clearly not the case, as what is broken are those same things, especially the global monetary system that as it is will not allow that occur. Therefore, it is beyond misleading to shift the debate to Trump policies when the far more relevant reckoning of past policies, mostly monetary, has never been undertaken (and only intermittently discussed).

China’s problems won’t just start with Trump, though there is every reason to suspect that is how they will be framed from this point forward; especially as it amounts to a backdoor, indirect defense of orthodox economics. It isn’t even really about Trump, in this sense, as if economists can blame further lackluster or worse economic conditions on what Trump proposes it will greatly soften the blow of their own spectacular failure up to this transition point. I have no doubt that is the agenda.

Unless the global economy actually recovers, and neither I nor the most relevant markets seem to believe it will, you know what and who will be blamed this time. “Unexpected” is about to be retired from the mainstream vocabulary.

Stay In Touch