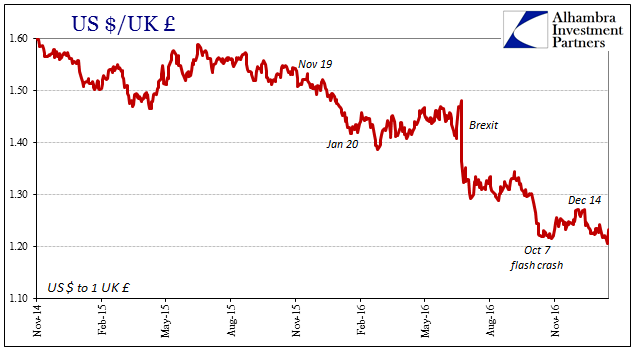

There are a great many great things afoot, so it might be understandable some transferred excitement (or dread) into the realm of global currencies. The British are set to leave the European Union, though nobody really knows what that means let alone what it might lead to. While the US was closed for MLK remembrances, sterling was all over the place. First it almost crashed when Prime Minister May’s (leaked) speech seemed to indicate a so-called “hard” Brexit, and then surged when her full remarks indicated instead a role (and possible impediment to Brexit) for the UK parliament.

If currency volatility were limited to just the pound, then Brexit might well be the primary instrument of uncertainty. But there is far more going on than just UK or European politics, and that almost always means the dollar. In trying to reference all this, the most the media will give out is the traditional framing no matter how many times it has been invalidated over the past decade.

“It’s almost certain that Trump will not reappoint Janet Yellen because, by the time that comes up a year from now, she will have already made him mad by raising interest rates,” Gordon said. “The appreciation of the dollar that comes with the higher interest rates is going to cause an increase in the trade deficit and undermine his own desire to reduce the trade deficit. We’re going to have major impediments to Trump’s achieving his goals for growth.”

While the UK struggles to define Brexit before its consequences, the incoming US President has made it clear he is no fan of a “strong dollar.” To many, that means going back to 2001 all over again, as if the Treasury Department can just command those kinds of relevant inputs. In the traditional view, that is at odds with the Federal Reserve, that by virtue of “raising rates” sets up this collision course.

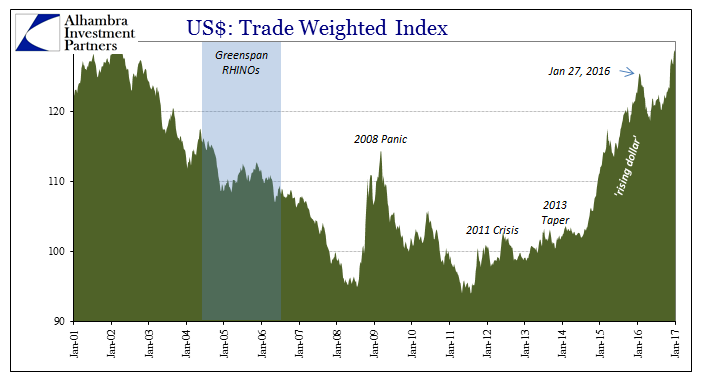

The only thing that is perfectly clear is that the mainstream sense of currencies has been way off for a very long time. Alan Greenspan raised the federal funds target rate 17 times during a two-year stretch in the mid-2000’s, and the dollar’s exchange value traded as if none of those ever happened. Now the Federal Reserve can only manage one per year and more than that no longer even has a federal funds target.

Despite the still, in the mainstream, unexplained differences of actual monetary policy mechanics, currencies since the “rate hike” in December are acting almost uniformly opposite all expectations. In fact, the only major to be behaving as it “should” has been the UK pound, before today’s trading.

From its flash crash in early October, sterling at least against the dollar had become moderately more stable, rising after a post-Brexit pounding (pardon the pun). This was during the period when other currencies indicated a great deal of movement and flight, including a global sovereign bond liquidation in November. On December 14, the direction suddenly changed not just for the British currency but practically all other majors.

Since the day after the Fed “raised rates”, the euro has been “stronger”, though we see very clearly such a description is highly relative and subject to harsh gradation.

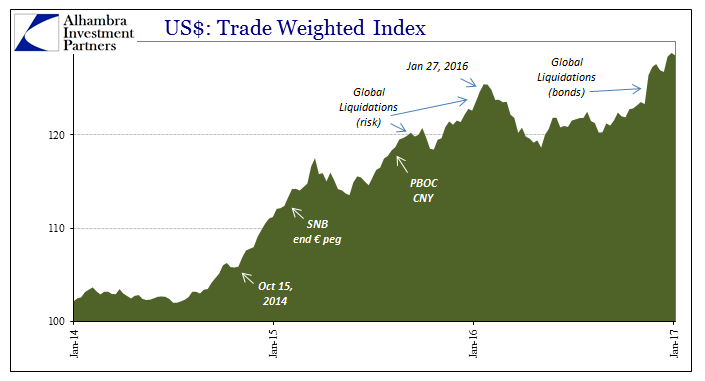

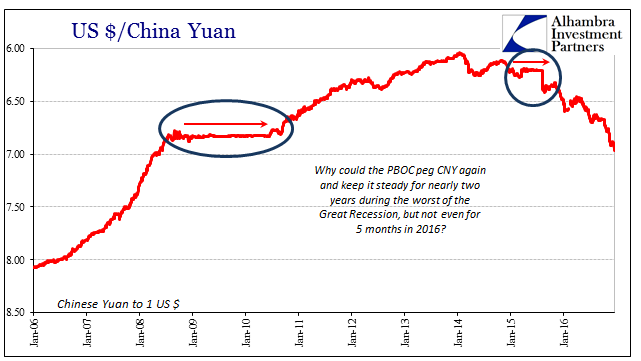

What is perhaps most prominent, and thus more important, is that the big moves that truly mattered were all two years ago. What has happened in the time since then has been try to reduce the big picture to something altogether different. In other words, the mainstream talks about Trump, “strong dollar”, and rate hikes as if any of those things actually apply here in any meaningful sense.

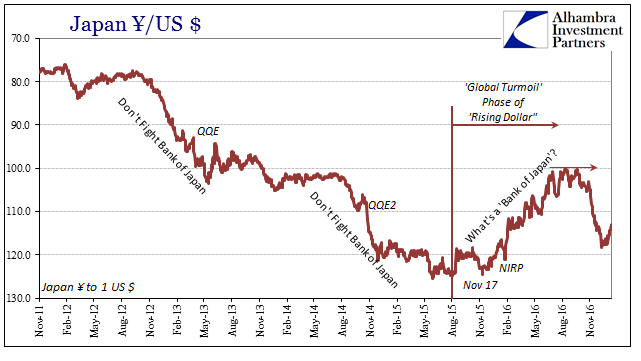

The Japanese yen was not one that made its big move starting in the middle of 2014. Instead, it would become a latter engagement only during some of the worst isolated periods of the “rising dollar.” Its ultimate bottom came in May 2015, but really didn’t rise sharply until August 24 that year. When it started rising in mid-November 2015, it signaled that “something” was very wrong, especially as it continued for months on that contrary course no matter what the Bank of Japan said or did (or threatened to say or do).

In many ways, JPY has become “reflation” itself, having started first sideway as the rumors of “different” abounded throughout the summer. Its enthusiastic return toward “devaluation”, while surely eliciting smiles and relief in the official sectors of Tokyo, again coincided with the bond liquidation in November. Since December 15, however, it is once again trading the “wrong” way and on so many levels.

The primary problem is that currencies aren’t what they used to be, a cliché that applies here in a way that isn’t cliché. Furthermore, the terms we use to describe these problems are by default imprecise. The “rising dollar” is, for the yen and others, a complete misnomer. What we are attempting to define, even measure, is not the dollar’s rise, or its fall, but rather its immediate instability and how that will progress into the longer run. As the global currency, the “dollar” is either the rock of stability (even artificial) or the agent of transgression.

That is what makes the big moves of the past few years the far more relevant baseline for both conditions as well as understanding. It was never about “rate hikes” or whatever the Treasury Department’s confused stance on the past might be then or in the future, it was the Bank of Russia in response offering term FX repos to Russian banks in both “dollars” and euros (likely “euros”) because they weren’t able to source them in any reasonable capacity on their own.

“Reflation” is an idea built upon “different”, that whatever the case for the past eight years the next part could be defined by success rather than constant failure because mistakes have finally been admitted, better ideas now to come. In the global economy, that will always be dependent on stable money, a lesson learned the hard way in the 1930’s and 1940’s only to be forgotten by the eager activists of the 1980’s and 1990’s. The single biggest threat to “reflation” is the same as what killed off the last one (and the one before it, and the one before that). On those grounds, not much, if anything, has changed. Or, as I wrote in late November, “It is just another prospective piece to a very complicated puzzle to consider amidst “reflation” that would need an end to “dollar” problems to actually become reflation.”

Stay In Touch