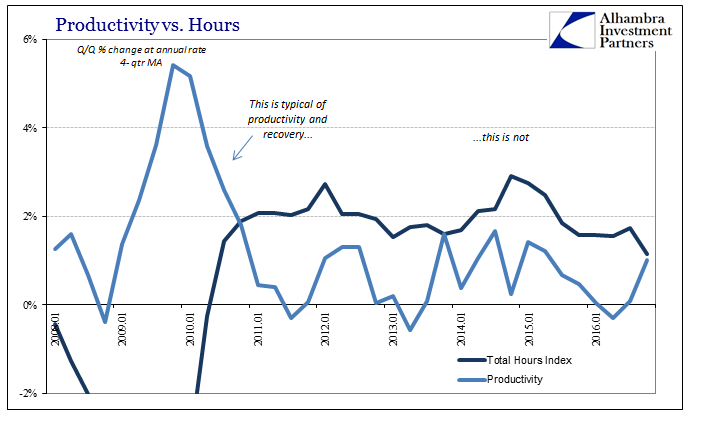

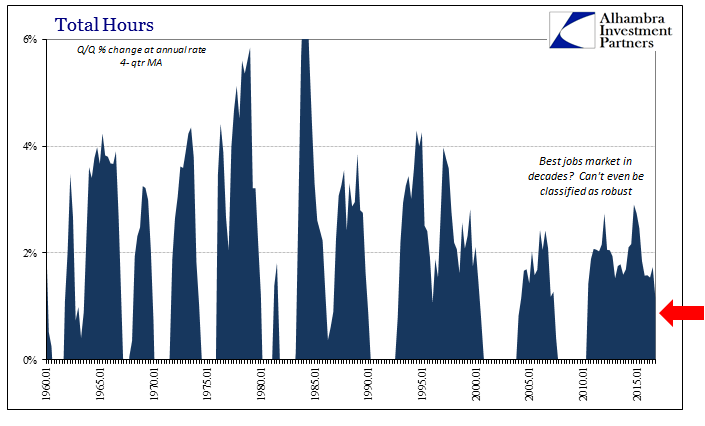

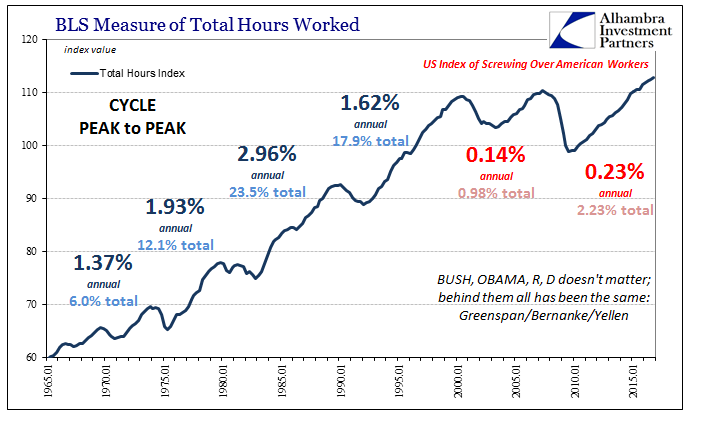

Productivity in Q4 2016 was estimated to have been 1.29%, suggesting that last quarter was merely bad rather than unusually bad as it had been just before. Productivity during what was the near-recession in the three quarters including and after Q4 2015 was negative in all three. That would suggest, strongly, why labor market statistics have uniformly described a rather sharp slowdown in labor utilization throughout 2016. The BLS estimates that total hours worked grew by just 0.91% Q/Q (annual rate) in Q4, following 0.61% (revised) in Q3. Last year closed out at what was the lowest two-quarter growth rate since the Great “Recession.”

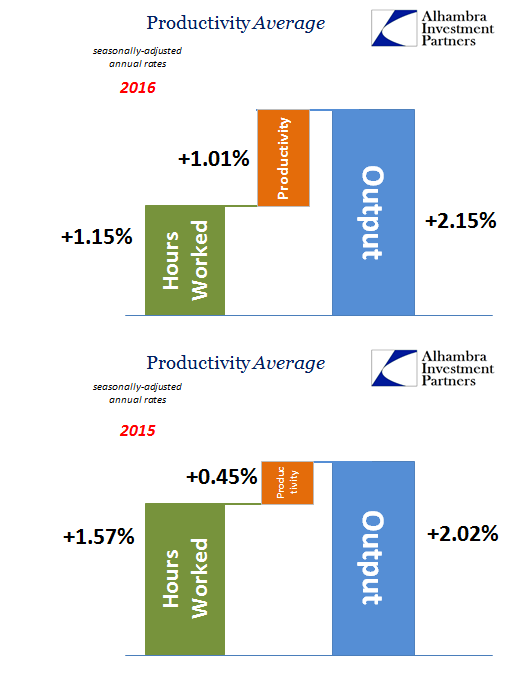

For the year overall, the average gain in total hours was a mere 1.15%, also the lowest since Q2 2010 when hours were still contracting. But because the BEA figures private output (subsection of GDP) was practically unchanged in 2016 as compared to 2015, the slowdown in labor translated into slightly more productivity, or at least productivity at a much less striking inconsistency.

Whereas total hours gained an average of 1.57% in 2015, they did only, again, 1.15% in 2016. With a small increase in private output, productivity is figured (as the leftover) to have increased to just over 1%. Productivity throughout the 1990’s, for the sake of relevant comparison, averaged just about 2% with 2.4% gains in total hours worked. Thus, the economy in 2016 was operating at about half pace on both sides. Given the way conditions developed in 2015 as far different than what was expected, there was clearly nothing “transitory” about weakness that continued for a second straight year (though it does leave the usual questions about the distribution mechanics labor to capital through productivity).

The FOMC policy statement issued yesterday doesn’t actually say a whole lot, and never does, but given these figures what it did say wasn’t just the usual boilerplate language, as it bordered on open duplicity:

Job gains remained solid and the unemployment rate stayed near its recent low.

Both of parts of that sentence may be technically true, as the unemployment rate has been 5% or less for each of the last fifteen months, while the BLS still suggests continued expansion in payrolls. Given the sharp slowdown in total hours, however, it more than suggests both of those numbers as being more hollow than representative. The productivity figures dating back more than just for the last two years have already raised this very issue, which is one prime reason why markets pay very little attention anymore to how the Fed classifies the overall economy.

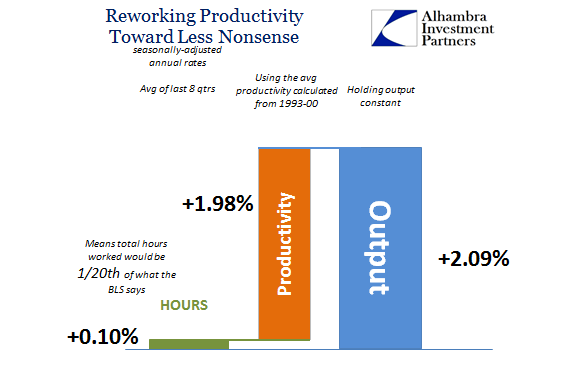

That point is perhaps best illustrated substituting (since productivity is a plugline) the average productivity from the 1990’s along with total output over the past two years. Had it been normal so as to match the rhetoric of the labor market and “strong” economy, there would have been barely any gain in labor utilization at all. In other words, for more than just the past two years but especially the past two years something has been not quite right about the economy given that the mainstream statistics meant to describe it in normalized terms can’t.

From this view, we can both see why wages remain subdued as did the economy itself. As noted last week, the Fed and economists got way too far ahead of themselves in 2014 believing in more so their own confirmation biases than rational analysis.

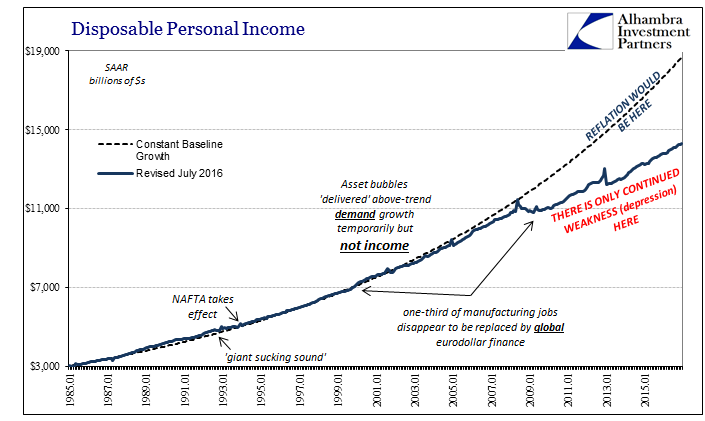

The “rising dollar” didn’t kill the recovery so much as reveal that it was never a realistic option. That should have been the diagnosis from much further back, but even in 2014, again, there were so many warning signs that bias (and some political pressure) is really the only answer as to why they weren’t heeded.

One element of this problem was something that Fed discussed intermittently, and more often harried at times of renewed crisis than in these calm spaces that might have been more conducive to insightful thought. In August 2011, at the height of what I believe has proven the fatal “dollar” squeeze, KC Fed President Thomas Hoenig vented to no one in particular:

HOENIG. If we’re going to take care of our employment problem, we have to increase production. And I keep asking the question as I look at the projections—that’s why I was asking Dave about the investment outlook. It’s going down, not up, even though we have dumped tons of money into this economy of ours, and here we are. How is further quantitative easing or further guarantees of zero rates going to take care of the fundamental problems that we’re not willing to step up to as a nation? I think that the central bank should be pushing other elements of this government to address long-term problems when it’s not. The same thing is going on in Europe where you’ve got the central bank in Europe now doing a bridge loan so they can have time to get their bailout, which the markets are already saying isn’t going to be enough. And we have a problem in this country where we need to be boosting investment, and it is languishing.

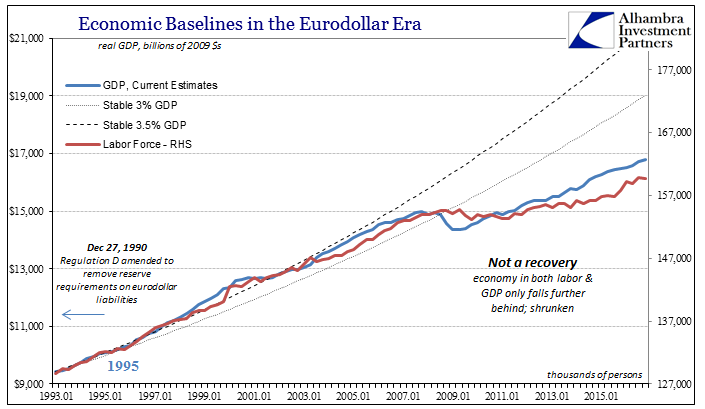

Setting aside all the very real and now revealed doubts about “dump[ing] tons of money into this economy of ours” through QE’s, whenever this point is entered into the official record it is never, ever followed by the words “stock” and “repurchases.” Monetary policy has a singular focus on the stock market, and the stock market knows that monetary policy has this focus, thereby, through mistaken assumptions, companies have spent cash on shares more so than factories and facilities.

And we can’t forget the more important element in that imbalance, the one captured all-too-well by the bond market, the eurodollar futures market, and others (WTI futures) where their curves have all flattened out horribly in the years since Mr. Hoenig spoke those words. That means opportunity, or lack of it, whereby in the financial sense financial agents would rather hold UST’s and other liquid assets than invest, and so too do corporate agents investing in their own “risk free” program of buying back stock. The lack of recovery becomes self-sustaining and self-reinforcing through this very channel – QE isn’t money printing and therefore no recovery is possible, leaving corporate businesses to buy back stock rather than invest in real economic opportunities that aren’t there, reducing even further the growth prospects in the real economy (low productivity), repeating the whole thing (including the QE part) over and over.

PLOSSER. And we must be careful not to leave the impression that we are reacting to stock market movements.

As if stock market participants didn’t think that way already? Unfortunately, this is not a condition that happened overnight during 2008; it was just that the Great “Recession” revealed what had been going on for many years before it. “We”, through ignorance of money, traded monetary growth for productive growth with the “best and brightest” apparently unable to distinguish one from the other, and are now stuck with the long run consequences of it. It’s not secular stagnation as some propose, so much as expert incompetence.

The charts below are really all the same chart looking at this very same thing from slightly different angles:

Stay In Touch