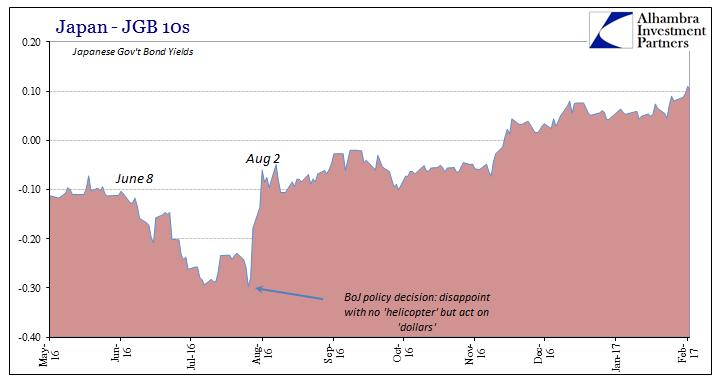

The Bank of Japan had announced another acronym with which to add to QQE, a term that already includes an extra “Q”, on September 21, 2016. It was a bizarre engagement, like something out of a TV advertisement for laundry detergent or diet supplements where the central bank marketed the same QQE that you always knew and loved but now with added YCC. Those additional letters mean “yield curve control” and in some ways it is a contradiction with QQE.

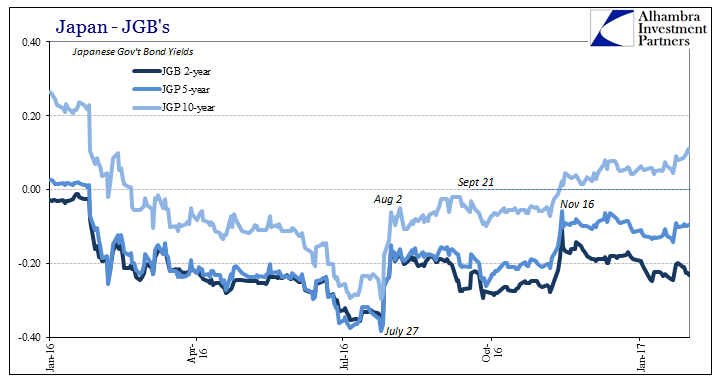

On November 17 last year, not quite two months into the expanded definitions, BoJ offered to buy an unlimited quantity of 2- and 5-year bonds at -9 bps and -4bps. Those bids were well below market prices at the time, so small wonder there were no takers. There weren’t meant to be any, however, as it was simply a demonstration of intent. As usual, the effects have been debatable.

When BoJ established the offer, the 2-year JGP was “yielding” -11 bps. The yield fell back lower (more negative) again afterward, as low as -24.6 bps before registering -23.1 bps Friday. The 5-year JGB was -5.7 bps the day before, -10.1 bps the day of the announcement and like the 2-year moved lower in yield (higher in price) at least at first. The lowest point was reached on January 24, but the last yield last week was -9.6 bps, just a little less than the day the policy tender was put in place.

The differences in response to the added YCC are related by length of maturity, raising some serious doubts about ability. Why did the BoJ focus on 2s and 5s rather than 10s which had at that moment violated the zero yield threshold for YCC? It was a curious omission, one that BoJ finally felt compelled enough to act only last week. In that way, BoJ seems to have established not yield curve control but rather its opposite. That may have been the central bank’s primary worry on November 17, as hoping to “scare” the yield curve into compliance with its new JGB bids.

That has been an open question the whole time, as it was never much of a directive to begin with. The BoJ left YCC as more of an open matter, as if it either wished flexibility with regard to using it, or, more likely in my view, they worried over the implications if they were ever caught being unable to accomplish more defined objectives.

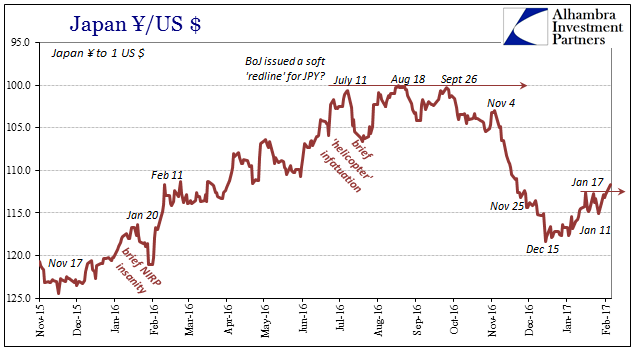

When all this was taking place in November, and the bond rout was felt all over the world and not just Japan or Asia. This was in every respect a total reversal of correlations, where USDJPY basis swaps were sharply falling. From July 2016 through the end of September, basis swap spreads (negative) had stabilized as the BoJ at its July meeting had finally addressed “dollars” rather than add more QQE (as was widely expected, if not the full “helicopter”). In October 2016, the negative JPY basis actually shrank after a very turbulent quarter-end, moving up to as high as -55 bps.

Then it all reversed again around October 25 (and the start of copper’s run coincident to heavy indicated RMB interventions from the PBOC). From that point all the way to the end of November, USDJPY basis swaps sunk to a new record negative at around -92 bps, considerably less than either the July low or the end of Q3.

Again, this part was nothing new for Japan, as the “dollar shortage” has become a more and more common feature. In fact, it was an almost perfect representation of the “dollar” problem where JPY rose in contradiction to the stated BoJ policy (lower, lower, and lower). In November 2016, however, though the “dollar shortage” grew appreciably worse, this time JPY suddenly seemed to follow the BoJ mandate, and did so with unusual vigor. It’s difficult if not impossible to attribute this complete turnaround to YCC.

JGB yields, too, were caught amidst a hard reversal, whereas before July yields fell and often sharply as the JPY basis did. In November, inversely, JGB yields were then rising, often sharply, even as JPY basis spiked more negative. These complete turnarounds in correlations were worldwide, even where CNY was concerned.

The experience with Japan suggests the outline of the global narrative, one defined along the baseline by basis swaps (“dollar shortage”) but with dramatically different outlets of it. The turning point seems to have been the July BoJ meeting. That the central bank would react at that particular point, serious erosion in confidence as well as “dollars”, to the currency more than QQE or even economy was hugely significant. It suggested that there actually was a point where central banks would move away from what clearly wasn’t working and in all likelihood never would.

As “dollars” remained in short supply throughout, where once risk assets were sold and “flight to safety” the preferred outlet of investing, sufficient embrace of confidence turned it all around to where “flight to safety” was sold and risk (to a limited extent) embraced.

The episode in the middle of November, however, reminded markets that there are actually two parts to bring about actual reflation; central banks’ willingness to do something different is but the first step. The second step is much more difficult and fraught with complexities and feedbacks that may doom it no matter what (not the least of which is the “dollar shortage” that never goes away). After signaling that it was willing to be different, the BoJ (as all other central banks) at some point has to prove that it can be different.

The point isn’t even the JGB 10s so much as it is a further example of more bungled policy. If the market was hoping that now, for once, BoJ would start to get it right, the half-hearted approach over YCC could only reinforce persistent doubts represented by the JPY basis to begin with.

It is one thing to finally start to deal with an enormous “dollar” problem, quite another to deal with it effectively. How can BoJ credibly claim to be able to fix the big problems when it can’t address those of its own making? The BoJ instead of demonstrating evolution in action as well as policy simply reverted to prior form with different letters now attached to it. It seems to have robbed a good deal of momentum from “reflation”, and perhaps rightly so. JPY since December 15 has renewed its upside tendency while the short end of the JGB curve is ridiculously negative all over again.

The belated attempt to “rescue” the JGB 10s last week has appeared to have been recognized in JPY. For almost three weeks, the yen exchange had been stuck at around 112.60, but has now shot past that in trading so far today. As of last check, the exchange value is 111.80 and still climbing.

What everyone desires is effective policy of whatever format that will end the global depression (represented by these shriveled curves that are related to negative basis swap premiums), and for a brief moment last summer there was a glimmer of hope not necessarily in a specific program but, again, this idea that having failed miserably up to July 2016 central banks would have no choice but to become less ideologically motivated.

QQE with YCC was in theory consistent with that hope, but has instead turned out to be yet another embarrassing bungle. The market wasn’t expecting BoJ to cure all ills with this one new twist, but it surely hoped that it would at least exercise the YCC with something far closer to efficacy than has become standard practice and expectation. “Reflation” in this instance was built around baby steps, central banks maybe getting some smaller things right so that eventually they could use those victories in finally crafting solutions to the bigger issue. Step two is really about reestablishing lost credibility.

That may have been all the market was asking for during that period, just some small piece of evidence upon which to build further confidence. As usual, however, it was in all likelihood asking too much, especially from the Bank of Japan. In that respect, practically everything since July has gone wrong; the “dollar” program hasn’t had any lasting positive effect, and now YCC is out of control.

Stay In Touch