In what has been one of the more remarkable turnarounds in perhaps all economic history, to start the 1980’s the Federal Reserve was roundly rejected. The US central bank was thought a collection of anachronistic malcontents who were unequal to every task. They had made a mess of the 1970’s, and furthermore they were the last to figure that out. In the Spring of 1980, Minneapolis Fed President Mark Willes would write for his branch’s Quarterly Review:

Nobody is very happy with the conduct of monetary policy. The economy has performed badly, particularly in terms of inflation and the large costs that go with it. And the near-term outlook for the performance of the economy is grim. Many critics accuse the monetary authorities of failing to deal effectively with the problems we have faced, and virtually every policymaker admits that, in hindsight, we have made some mistakes that have added to our economic woes.

Why did it take prolonged empirical refutation for monetary policy to come to terms with its shortcomings? The answers to that question perplexed policymakers throughout the decade of the 1980’s. Among the first and most widely accepted explanations was what Robert Lucas had proposed the decade before. Prior to then, economists worked off of an adaptive expectations model, meaning, in short, that econometric regressions assumed people and economic agents looked only to the past when considering their analysis for the future.

Lucas, more fully developing a radical idea first proposed by John Muth in the early 1960’s, sketched out rational expectations. In this framework, the models assume that people and economic agents choose optimally given their own limitations of information. In other words, individually people might make mistakes subject to the constraints of information, but systemically there cannot be any, or at least none that might be prolonged (a kind of information arbitrage that works out as efficient markets theory).

The pre-eminence of Lucas was in adapting rational expectations theory to the reality of the Great Inflation; showing that it could explain why the Phillips Curve so failed policymakers. Based on the original exploitable Phillips Curve proposed in 1960 by Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow, economists actually believed that working through economic policy at the US Treasury Department, with the Federal Reserve as its monetary agent, they could engineer unemployment right out of the country by quantitatively exploiting the tradeoff with consumer prices. As Willes wrote:

Models based on adaptive expectations, which worked well in the 1960s, failed dramatically in the 1970s. In the early 1970s such models predicted, with a high degree of confidence, that the United States could drive its unemployment rate down to 4 percent if it were only willing to live with a 4 to 5 percent rate of inflation; with a 5 to 6 percent rate of inflation, it could virtually eliminate unemployment.

This was, of course, not just wrong but categorically so. In economic, political, and social terms, the decade of the 1970’s is not remembered fondly in most corners of the world. We appear to be at a similar crossroads today, one which in many ways is the mirrored opposite of that time.

The consequences of ideological predisposition to bad, flawed theory thus established, how did the Fed, in particular, turn it all around in their favor? In a relatively short amount of time, the central bank went from disgrace to the exemplar of all bureaucratic ideals. Much is made of Greenspan’s tenure in accomplishing the feat, but it started with Volcker. He is given credit, as the Chairman of the Fed, for “defeating” inflation and establishing the baseline for what would be called the Great “Moderation.”

A full part of the reason for this reputation relates to how economists after botching the 1970’s again botched the 1980’s, or at least its first half or so. Very few of them saw inflation as falling back for more than a temporary reprieve, related to the sustained downturns in the earliest years of the decade that were all widely believed a product of Volcker’s monetary policies. Paul Krugman, for example, in September 1982 authored a memo jointly with Larry Summers where both were new members of President Reagan’s (yes, that is correct and not just some bad historical fiction) Council of Economic Advisors, titled The Inflation Time Bomb.

As real intrest [sic] rates decline and the economy recovers, we can expect the real exchange rate and real commodity prices to return to approximately their historical levels. Our very rough guess is that correction of these distorted relative prices will add five percentage points to future increases in consumer prices and about two percent to the GNP deflator. This estimate is conservative in that it assumes stable oil prices.

They expected economic conditions to go right back to those like the 1970’s. But because that didn’t happen and instead the opposite conditions resulted, economists looked for answers in what might have changed between the 1970’s and 1980’s and found in that difference only (or mostly) Paul Volcker. It also fit well within the growing acceptance of rational expectations over adaptive expectations – under the former economic agents would expect a credible monetary policy to work, and therefore would act on those expectations as if they did. Once inflation came down and stayed there for the balance of the 1980’s, the credibility of the central bank was thus firmly established and anchored in all expectations from there forward.

From this older view, we can overlay our current conditions so as to see quite easily where they violate these theories (without ever having to establish how or why rational expectations is invalid, which it is). Again, back to Willes:

When the monetary authority has more information than the public, for example, policy can affect the variance of output (though not the mean). To choose the right policy, however, the monetary authority must know precisely how the public’s information differs from its own. When the public is slow to learn about a policy change, for another example, the monetary authority can affect real output. But here again, the monetary authority must know precisely what the public knows, plus how it learns, before it can devise the right policy. Policy analysis no longer rests on estimating a simple relationship between inflation and unemployment. It now requires the policymaker to know precisely how information sets differ and how people learn.

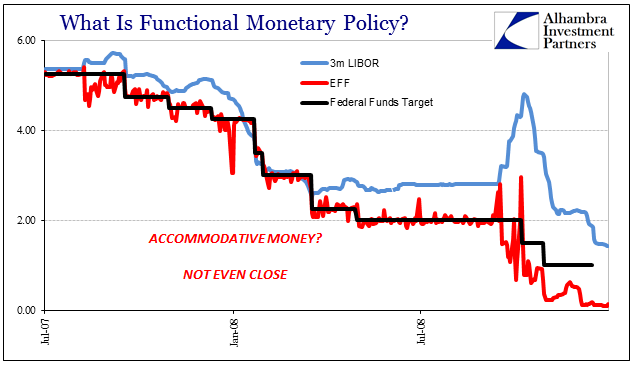

This is that part of rational expectations that most people are familiar with in layman’s terms – the so-called policy shock. That is what QE was designed for, and what has been taken to its most extremes (especially Japan and its quadrillion flirtation). Obviously, it hasn’t ever come close to working out, a fact first established a long time ago when any single central bank’s first QE was inevitably followed by a second (and a third, and so on). In official terms, these are the “diminishing returns” of additional “stimulus”, as it no longer shocks.

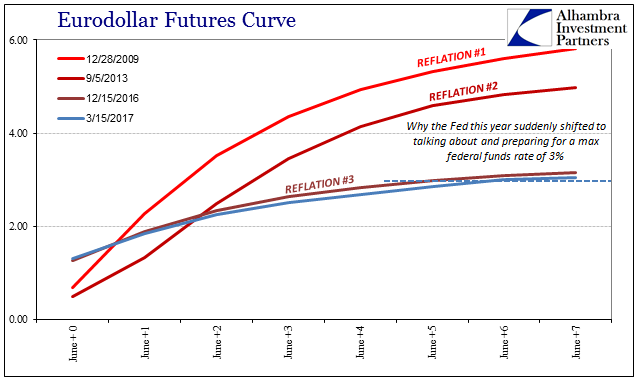

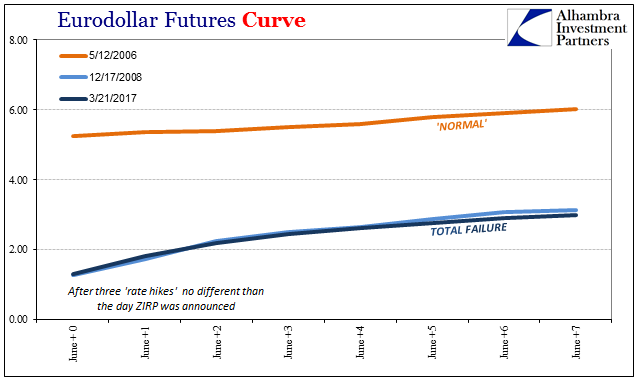

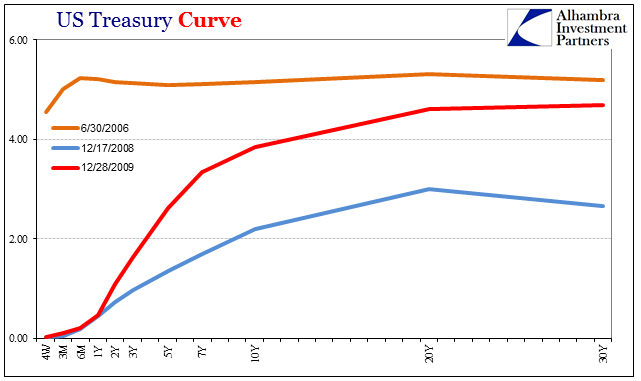

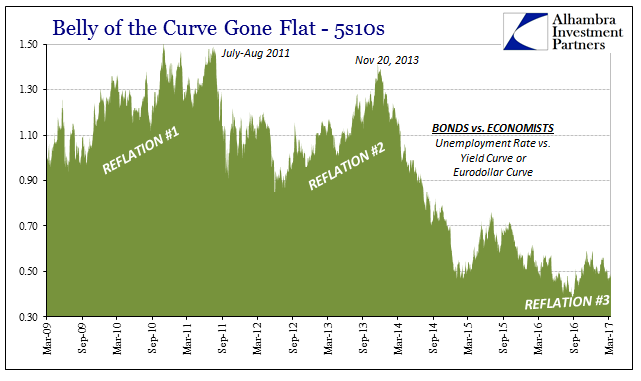

And it was this very idea which proposed to the Bank of Japan QQE of enormous proportions, to get the shock back in shockingly irresponsible. As in Japan and everywhere else QE was tried, we can observe the lack of transmission followed by those diminishing returns. We have eurodollar futures and the UST curve in the United States that show up in “reflation” at various points usually in close relationship with the latest monetary policy “shock.” The diminishing effects of each “reflation” are that theorized information asymmetry between the Fed and at least financial agents disappearing – by this latest round, markets don’t even buy recovery, meaning the success of monetary policy. It has become, again the mirror of 1980, unanchored.

The mechanism for that, however, is even more primal and forcefully established – the real economy. For while the policy “shocks” created market action they did not create economic action in nearly equivalent terms. Each time markets would trade in anticipation of monetary policy working only to find that it didn’t. What markets have been conditioned to over the past decade is how monetary policy models are just as invalid as they were during the 1970’s; only this time the economic direction is not high inflation and a high unemployment but instead low inflation (disinflation) and low unemployment (but not high employment). Apart from stocks, a very prominent refutation for rational expectations, there is very little belief today that central banks can do anything to change this disastrous condition.

It as a complete turnaround, as in more than just eurodollar futures and sovereign bond curves the information asymmetry about monetary policy has been resolved in the opposite – central banks rather than knowing more than markets about economy and policy have shown quite clearly that they know less. We are right back at 1980 all over again. Thus, it is appropriate to quote Willes one more time:

It says that we currently know very little about the appropriate use of economic policies. It says that macroeconomists have to develop more explicit models of economic behavior. It says that the answers we seek are much more subtle and complex than we once believed.

Because we know so little, economists and policymakers should be considerably humbler in their policy prescriptions. Simple correlations between inflation and unemployment, for instance, cannot be reliable guides to policy. At most, we can say that since policy actions can easily add to the economic uncertainty, whatever rules we happen to choose should be well defined and well understood. For policymakers to advocate much more than this will require significant theoretical and empirical breakthroughs in research.

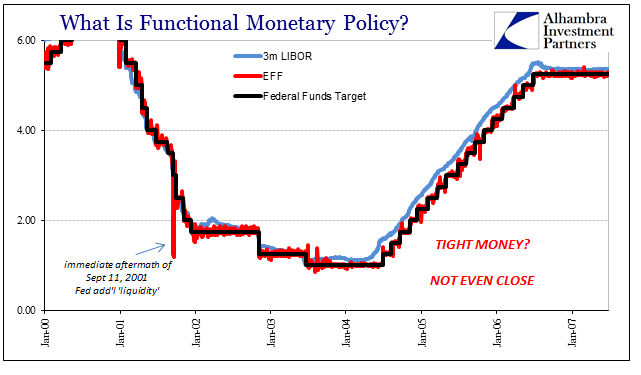

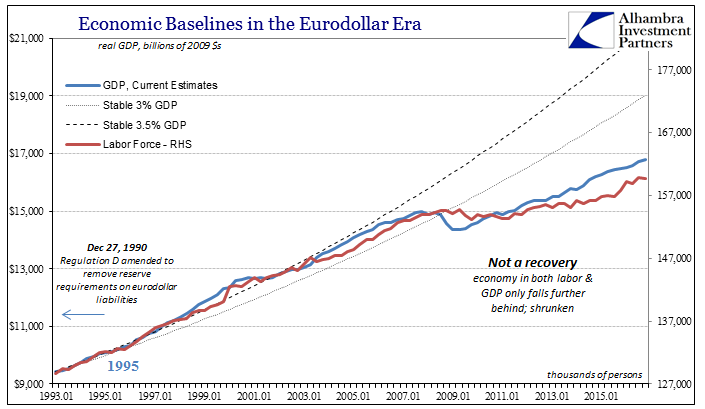

Economists and policymakers believed that they had in the 1980’s made those breakthroughs, but instead they committed the worst sin of any statistician – they confused causation for correlation. If we instead rationally adapt our view to monetary policy especially in the 21st century, it appears almost perfectly that it did not lead economic conditions but reacted to them as “something” else injected causation.

Since rational expectations appeared to solve their dilemma, economists made what I think an easily established fatal mistake. The disaster of the Great Inflation was stimulated by a misunderstanding of money and economy, which was “solved” for economists by rational expectations as making econometric models more consistent in mathematical terms – meaning fitting modeled results with what had already happened. It was a curious development given that in any other discipline the most likely result of witnessing the terrible consequences of so much bad monetary theory would be to revisit what was known and understood about money. Or at least questioning the whole idea of modeling rather than always looking for a “better” one.

Policymakers used to believe in the exploitable Phillips Curve, but only replaced it with an exploitable monetary policy shock curve that ultimately has proved just as inelastic. The Great “Moderation” wasn’t the fulfillment of generations of study coming to fruition, it was an artificial island of calm (made by exogenous, uncaptured money growth) in between Economics’ usual condition of getting everything wrong. The problem with monetary policy was never its adherence to one particular model or another, but rather that it has chosen to follow exclusively statistical models and thus by default forsaking useful knowledge for mathematical trivia. We could easily rewrite Mark Willes’ piece on the subject of wholesale money rather than adaptive or rational expectations and the conclusions would be exactly the same. Some things never truly change, even if they might seem to for a little while.

Stay In Touch