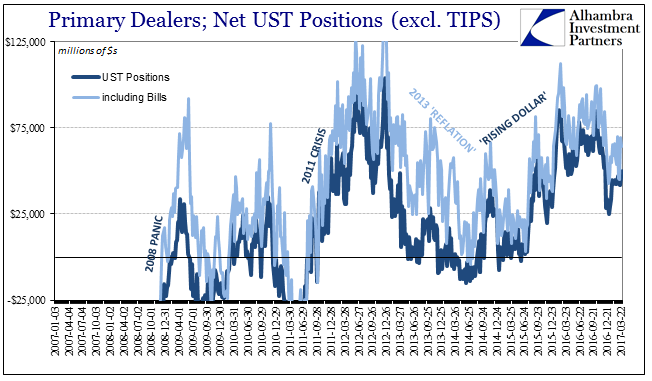

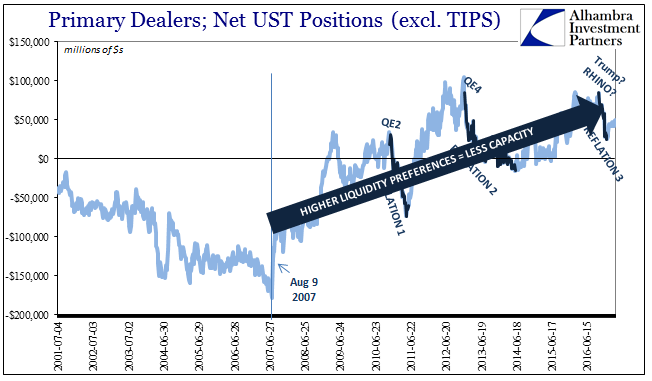

Primary dealer holdings of UST securities have been on the rise again. This sort of warehouse activity is drastically misunderstood, exemplified best when last year around this time surging dealer inventory was blamed on those banks’ purported inability to sell off their holdings. It was an absolutely absurd idea for several reasons, but most prominently the overwhelming demand at the time for those very securities.

At +$49 billion, net, across all coupons (but not TIPS), and +$64 billion including bills, dealer inventory levels are as high now as they were in early January 2016 during that initial liquidation phase. Those levels are up from +$25 billion coupons and +$45 billion including bills to start this year.

Despite “reflation”, clearly dealers aren’t yet willing to disgorge their holdings as enthusiastically as they did in 2013, let alone 2011 and nothing even approaching the pre-crisis era. It is another area where this “reflation” is appreciably less embraced than the last one. In terms of this data set, what we are seeing are systemic as well as tactical liquidity preferences being expressed by those directly inside of the wholesale (shadow) world.

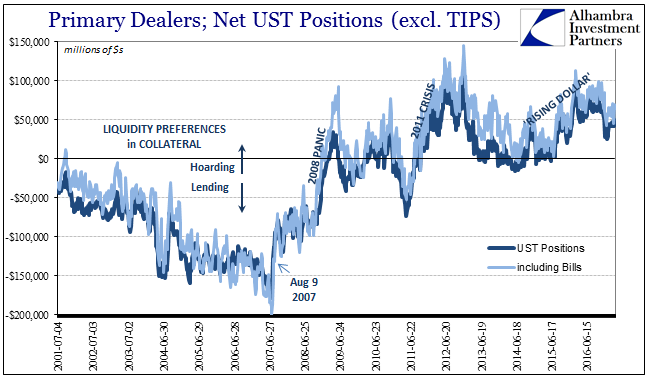

Since dealers by and large are not speculating on the direction of interest rates either way, their tendency toward a net positive position or a net negative one relates more to collateral and financing opportunities versus costs. Perhaps the largest potential “cost” is volatility, where in repo markets funding inflexibility can be expressed as dealer “hoarding” of UST’s or MBS. That is, in fact, what we find at each interval of crisis going all the way back to the summer of 2007.

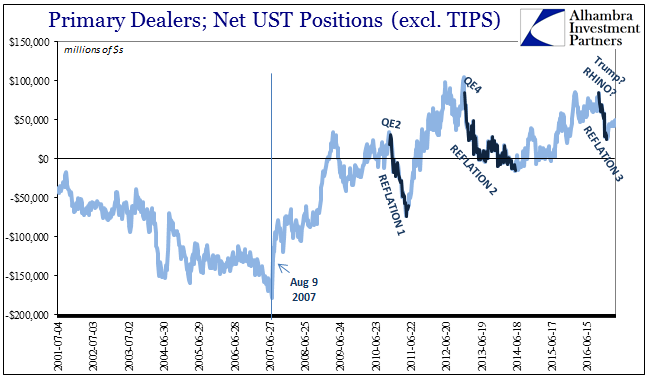

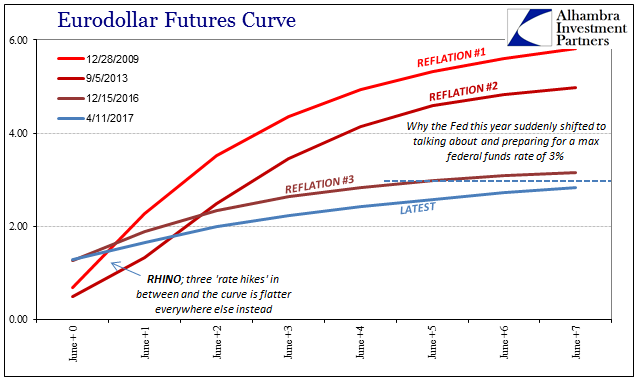

Again, not only do we find these individual episodes or funding spasms in the direction of “hoarding”, overall there is a clearly established structural break right in August 2007. The differences in how each version of “reflation” has played out are very much like the shrinking of eurodollar or UST curves over the last decade.

This singular direction would rule out regulations as the principle causal instance contributing to systemic illiquidity. Ten years ago, fluid collateral and overall financing moved easily all around the world but since then it has become only problematic and chronically so. It is another parameter defining reduced systemic “dollar” capacity, that while not acting in a straight line (broken on occasion by temporary bursts of optimism, or “reflation”) is inarguably a single trend. More importantly, that baseline remains quite clearly intact.

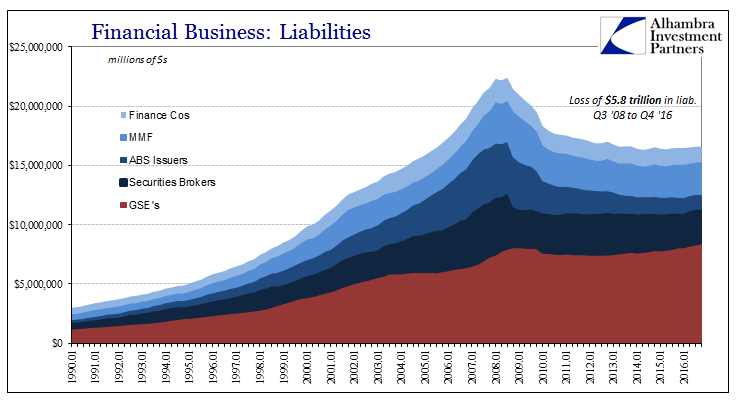

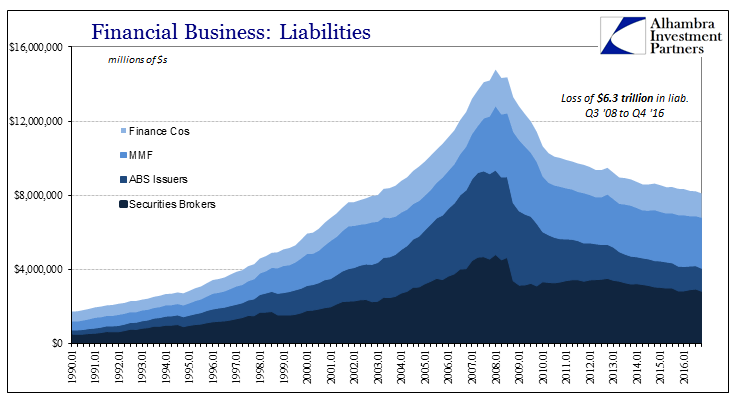

By further searching the capacities of those financial participants who do business with dealers, we should be able to find enough similarities so as to corroborate this view. And that is what the statistics all tell us, though in truth the indicated reduction in capacity from the shadows makes dealer liquidity preferences seem almost optimistic by comparison.

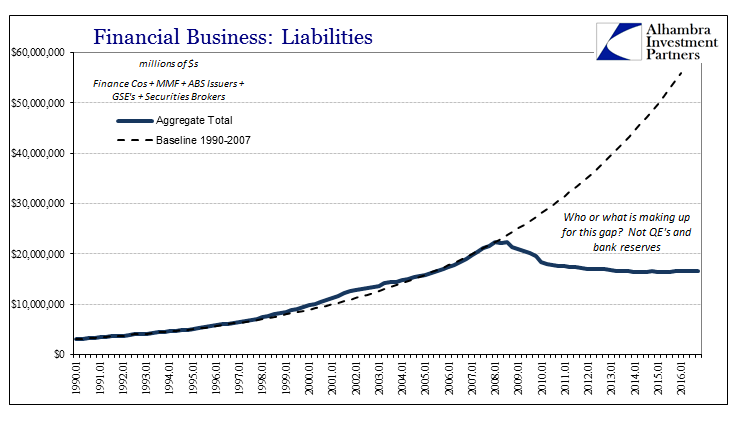

The chart immediately above and the one just before it are different sides of the same processes. Persistent reverses in the scale and imprint of the wholesale financial system mean a significantly less robust “dollar” market in between all of these various elements and participants. That by itself would not necessarily constitute the kinds of problems we have experienced since 2007, at least if there was something, anything, to take up the lost capacity in these shadow channels.

The QE’s were supposed to offset at least part of this deficiency; the Fed would offer its balance sheet to replace the loss of private shadow capacity. At least that was the narrative. But QE’s and bank reserves are not, despite orthodox contentions otherwise, good enough substitutes for the full range of dealer activities. What the dealer holdings in especially the first two “reflations” tell us is that like investors in eurodollar futures or UST buyers the banks initially thought that monetary policy might work as advertised. And like those others, dealers have, over time, especially after the “rising dollar”, learned to discount if not ignore monetary policy and bank reserves in total.

In the pre-crisis period with volumes, essentially the real money creation, always rising and rising rapidly that meant there was always someone willing to buy risk (and usually pay serious premiums for the privilege). That was, in fact, the mandate for all these various entities including the GSE’s. From the standpoint of a liquidity provider, that meant limits could always be tested because if there was ever difficulty it wasn’t hard to find some other counterparty to lay off risk (in a whole lot of different ways). There was no need to hoard UST inventory because there was huge demand for it in collateral lending (and fat enough spreads to make it handsomely profitable) but more so because if a repo trade went sideways there were any number of ways to replace the funding avenue.

Limiting capacity in systemic fashion is limiting choices, and therefore through nothing more than prudence would dealers and indeed all participants err more on the side of caution (hoarding). And as nothing ever seemed to get fixed by any amount of QE, the tendency toward liquidity drives that much further. If there aren’t as many choices, fewer willing or really able to buy risk at a moment’s notice, then all that is left is for you to realize you are at great risk of being stranded alone at the margins of funding. And what was the “rising dollar” but exploring the degree and depth of these islands that only confirmed liquidity preferences were the right direction.

It is one more aspect to “reflation” that must at some point live up to the name. I don’t want to make it sound as if an exclusively binary option, but given the lack of any meaningful progress or even difference anywhere it almost has to be at some point. Either things actually change and “reflation” deserves out of the quotation marks or it ends like the other two. Outside of the media and economists wholly desperate at this point, disbelief or pessimism persists for very good, well-established reasons.

Stay In Touch