There isn’t much data available on the mechanics of lending or the other side of it borrowing. It’s a topic of interest nonetheless given the crucial role (sadly) of debt in determining the marginal economic direction (second derivative). A financialized economy is a drag without credit growth.

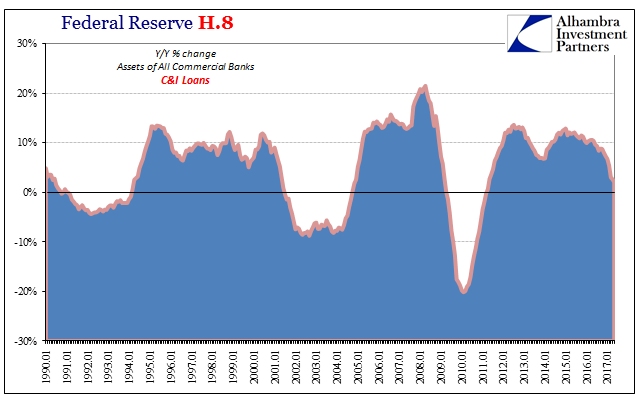

One of the more encouraging signs on that account was an acceleration of growth in commercial and industrial (C&I) loans in 2014. This category of lending/borrowing relates to the vital effort toward productive capex. Given the problems of this economy and the dearth of productive investment, the languishing of C&I after the 2012 slowdown was an ominous sign over the potential implications for that slowing.

The growth rate peaked, however, at just shy of 13% year-over-year in January 2015. That was slightly slower than the growth rate at the top before the slowing in 2012; 13.6% that July. Therefore, there wasn’t really anything all that robust about this segment of the lending market, at least in terms of the high side.

From that point forward, C&I lending has only further decelerated. On its own that might not have been much of a concern, as bond market offerings have been especially robust going back to 2009. In fact, the slight deceleration in 2013 was in all likelihood related to a surge in bond issuance after QE3.

But the “rising dollar” put a significant dent in the bond market so that 2015 and the first half of 2016 were scaled back in new financings. The lending market should have picked up the slack if it was all just transitory factors remixing the balance of corporate debt. Instead, growth in C&I never took off any further and has especially since the middle of last year tailed off considerably. As of May 2017, the latest data from the Federal Reserve’s H.8 series on Commercial Banks, reported C&I loans were just 2% more than what was estimated for May 2016. That’s the lowest growth rate since 2011, with no end yet in sight for this downturn.

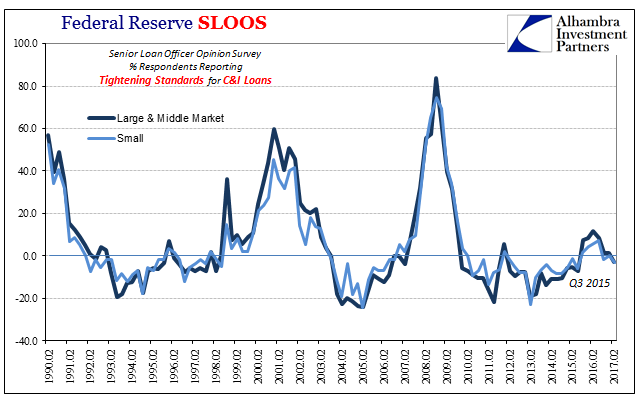

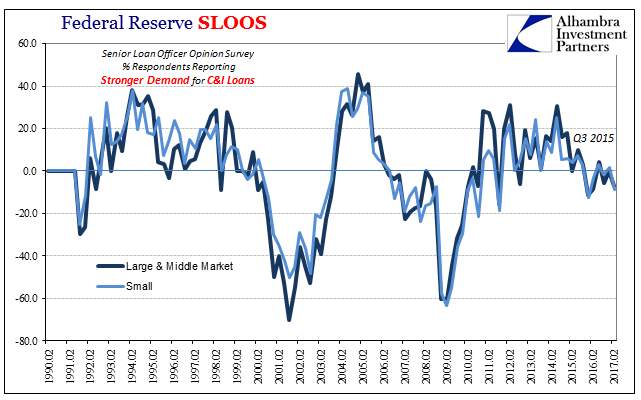

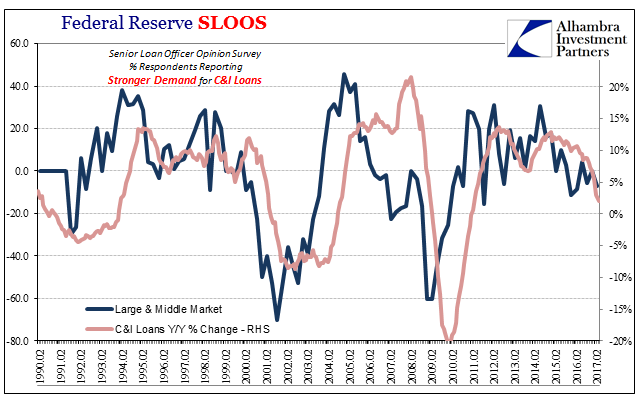

The Federal Reserve only offers one other data point as it relates to lending standards as well as estimates about changing demand for these loans. The Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) is just as the name states a survey of bank officials as to their assessment of the business credit market. It judges factors including the changing of lending standards, spreads over bank cost of funds, and C&I demand.

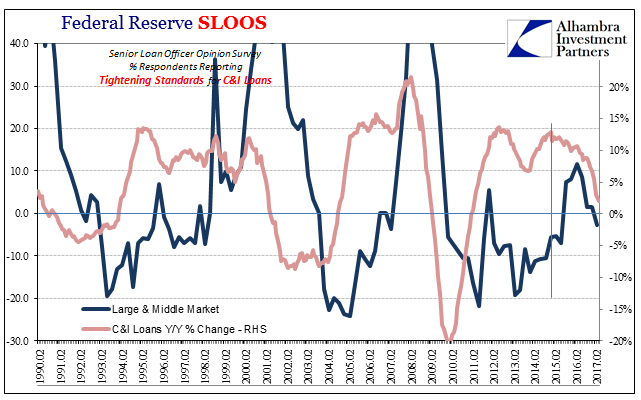

Though on either side the difference is far from huge, there are noticeable changes in both lending standards as well as demand. Standards were loosening in fairly normal cyclical fashion up until 2014. According to the SLOOS figures, that changed around Q3 2015 which fits with observable conditions (“global turmoil”) especially in lower quality and illiquid credit. It was not, again, a big difference but second derivatives even in survey data can be instructive.

You would expect a difference especially after what took place during that period. Some number of bank lending officers had to have reassessed their lending practices given the nature of lower quality credit trading as it did (leveraged loans and triple-hook junk in particular). It isn’t necessary for banks to be involved in those junk spaces to re-evaluate lending volumes, as the pricing history and the risk interpretations from it would apply more broadly to all classes of loans.

As far as demand, the issue is as always strictly opportunity. Global economic conditions worsened, as did domestic options, leaving commercial businesses to really think about their needs for the immediate future as relating to risks. Rising interest rates, especially LIBOR and therefore floating rate options (and potential refi reset points) merely increased the hurdle for additional borrowing against additional future investment projects. “Reflation” here is suggested as merely a financial or asset price phenomenon rather than more of a real economy one.

The confluence of these possible factors is as likely an explanation as anything else. Slight changes when combined can produce amplified results, particularly in this case where our ability to track and quantitatively interpret changes in bank lending is severely constrained. Logic dictates that some level of tightening in standards as well as reassessment of borrowing needs would result from the “unexpected” overall negative conditions of 2015-16. The degree of those changes is up for debate, as is what it means for the immediate economic future. To this point, it isn’t very positive for “reflation” or the long-awaited boost in systemic wages and income (via systemic productivity).

Lending is, after all, in some respects a view of confidence. Both lender and borrower have to feel, at the margins, on solid enough ground for marginal increases to occur. There are a number of important factors that ultimately lead to a decision, but by and large both lender and borrower are likely to be on the same page regarding opportunity. It should not be so surprising that perhaps both sides of the process aren’t as enthusiastic as they might have been just a few years ago, even if those changes are more subtle and opaque to this point.

Stay In Touch