The American view of the “rising dollar” period is one of truly understated appreciation. I wouldn’t be surprised if many of us didn’t realize there was ever a downturn to begin with, let alone one that flirted with proportions reaching recession. After all, the most widely felt effects didn’t manifest and really sting until the labor market slowdown dragged into this year.

We here in the United States were lucky, or at least avoiding the fate of being in the direct line of fire. It wasn’t the same overseas, and perhaps there is a great deal about the 2014-16 period that is even more unappreciated from our perspective. It was always that way from the very beginning, with late 2014 (apart from October 15) populated by overseas irregularities more than domestic. As I wrote in June 2015 about what had already transpired to that point (with a lot more to come, obviously):

To a great extent, Americans are both sheltered and wholly unaware, but the rest of the world is very much alerted to the continued downside of the eurodollar standard. Stocks may be at or near record highs (though broader stock indices, such as the NYSE composite, have gone nowhere since the “dollar” started to rise), but Brazil is in a state of total economic and financial chaos while China flirts with what was never thought possible (growth at Great Recession levels, a massive housing imbalance and now a stock bubble that in some ways puts the dot-coms to shame). There was a “dollar” system somewhat in place, largely before the middle of 2013, which supported all those but no longer does.

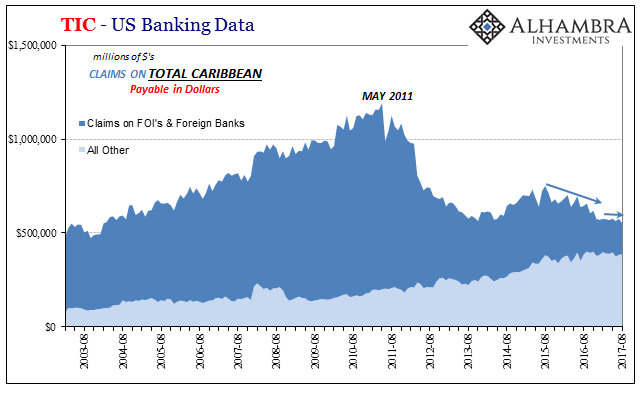

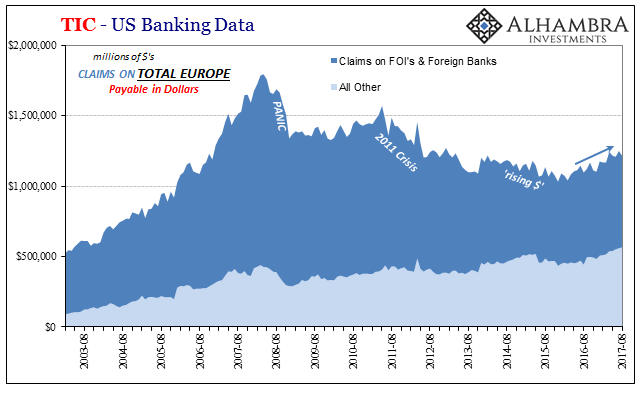

That’s the fascinating thing, in a morbid sort of context, about the eurodollar on its downside. It has always played favorites. In very general terms, the first outbreak of monetary deterioration (2007-09) which seemed to be the worst from our perspective was the least for the majority of the rest of the world. That one was focused on the US and to a lesser extent Europe. The return of crisis in 2011, the second event, was focused on Europe and to a lesser extent the US.

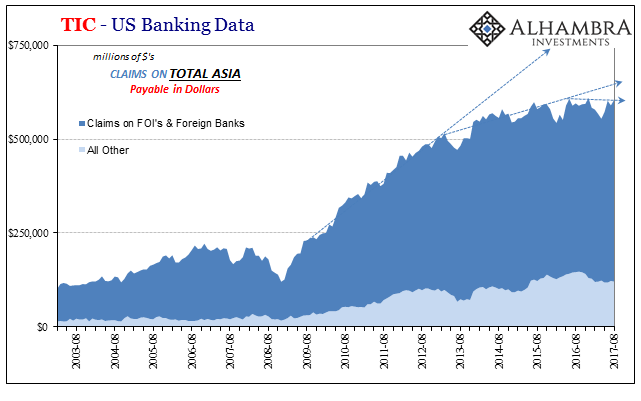

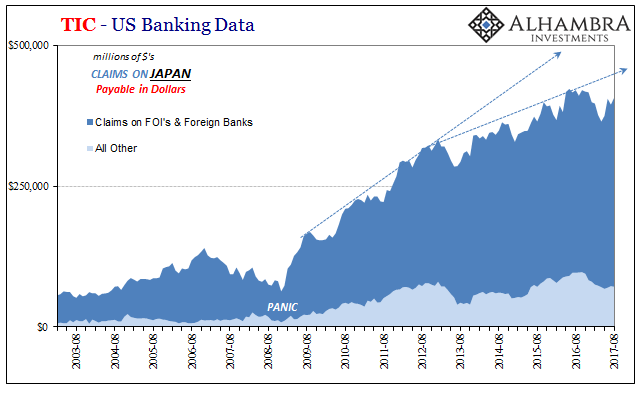

This last one, however, the “rising dollar”, was concentrated on EM’s and especially three of the BRIC’s, with relatively minor damage in the US and very little at all in Europe. We could go on at some great length for why that might have been, but very briefly it was in large part due to the evolution of the decaying eurodollar system. Almost from the bottom in 2009, its center of gravity shifted remarkably away from Europe toward Asia and FX derivatives. Japan and Japanese banks played a central role in that alteration (the real, true carry trade).

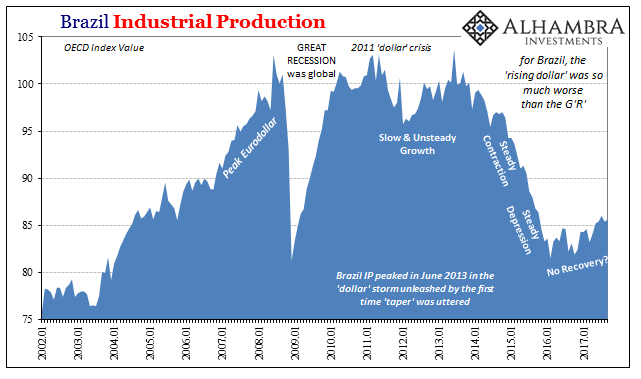

Given that global monetary orientation, it’s no surprise that Asia and EM’s were hardest hit during the global downturn 2015-16. In some places like Brazil, there is simply no comparison; the last few years have been total devastation whereas 2008-09 was a brief albeit deep interruption that the country weathered rather easily.

That, I believe, is a huge part of the problem today. It set expectations that were unrealistic, and certainly was a primary reason for the “dollar” shifting in that direction in the first place. If the US and Europe were hammered so hard the first time, and EM’s faring quite well by comparison, then the move in that direction holds some rational(ized) basis.

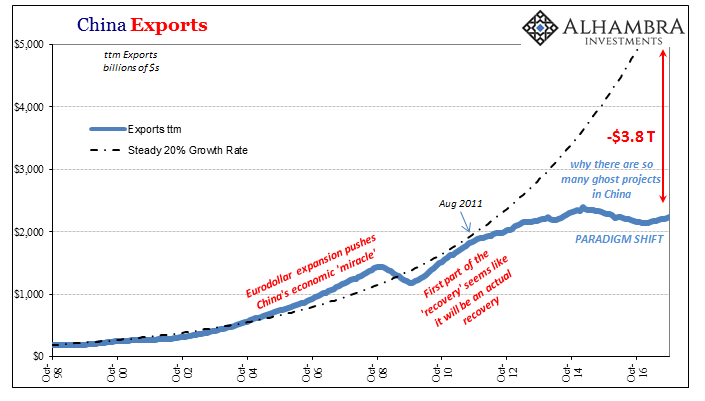

But it proved to be a false impression largely because it was also assumed that recovery would be global, even if delayed as a result of where and how that first “dollar” storm hit. Thus, the turn toward Asia in terms of eurodollar flows set up that region for the inevitable reversal once it became clear there was going to be no global recovery (the 2012 slowdown as a result of the 2011 “dollar” crisis). It’s why 2013 was so unusually violent overseas, if not yet in the more durable sort of way that 2014 forward proved to be; a transition between Asia-centered “dollars” and rethinking if those were really a good idea.

Therefore, again, we may have a hard time appreciating what has gone on overseas in these places where for them 2015 was like 2008 for us. The actions of Chinese authorities, for example, make a lot more sense realizing this difference.

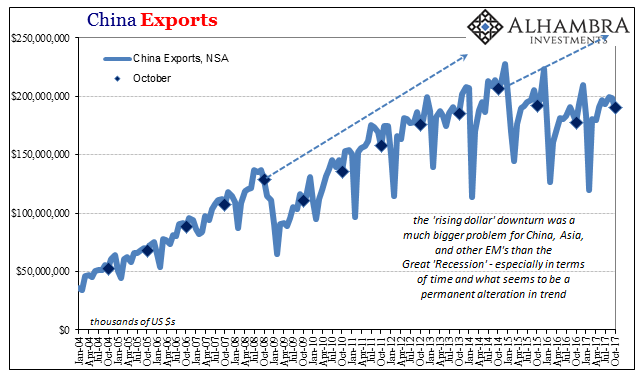

What matters now in 2017 is that after being subjected to that huge blow, there isn’t yet any sign of a rebound. Yes, there is an upturn in growth and activity, but that isn’t at all the same. Nearing two years distance since the worst of that period, it has to be clear by now that the “rising dollar” wasn’t just a temporary hit to Chinese, BRIC, and EM fortunes, just as it had become clear (to all but Economists) that the 2008 hit to the US economy proved just as permanent.

What makes this latest decay period so costly isn’t necessarily the absolute level of contraction it has attained (though it is for places like Brazil), but more so the costs in terms of time. These stretched out for so long can be incalculable, altering as they do deep and basic economic behavior (political and social behavior, as well).

The Chinese reported today that their total exports for October 2017 were just 6.9% above those in October 2016, but more importantly still 8.1% less than those in October 2014. I fully believe that the 19th Communist Party Congress held last month took on the unusual characteristics it did because of these results (not specifically China trade, but exports, imports, IP, etc.; the whole economic character which was been transformed by the “rising dollar”).

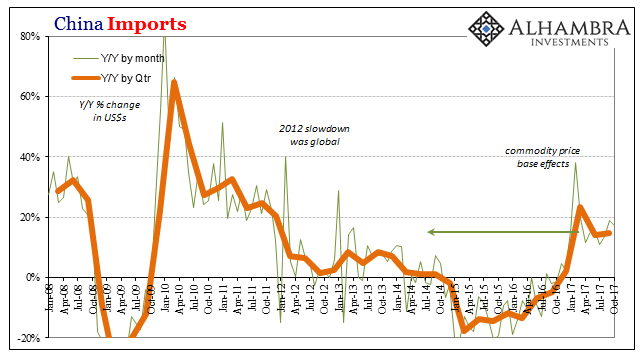

Even on the import side where growth has been relatively better than exports as well as compared to import growth in 2014, it still isn’t much of a rebound exhibiting full cyclical momentum as much as just positive price fluctuations in several important commodities (as well as the trade of African oil for payment of past “dollar” loans). Chinese imports were up 17.2% in October, nowhere near the 40-60% growth that the world experienced and counted on in recoveries from past contractions – including the one after 2008.

The great problem with linear thinking is that it places far too much emphasis on the plus sign, or the minus sign. The US economy would kill for 17% growth in anything, including imports, but for the rest of the world China’s 17% actually kills any chance of real global recovery. Global trade is the leading economic edge of “dollar” decay.

The last problem with all this is that it assists in perpetuating the orthodox fiction that each of these economies are subject to only their own idiosyncrasies, that China’s problems are Chinese alone in origin, or Brazil Brazil’s. The variability in how the eurodollar has affected each one seems to be consistent with that idea, if only on the surface (which is usually as deep as most Economists ever go). Complexity has been a eurodollar specialty from the very beginning (whatever that might have been), its decay still displaying the geographic dimensions on that list.

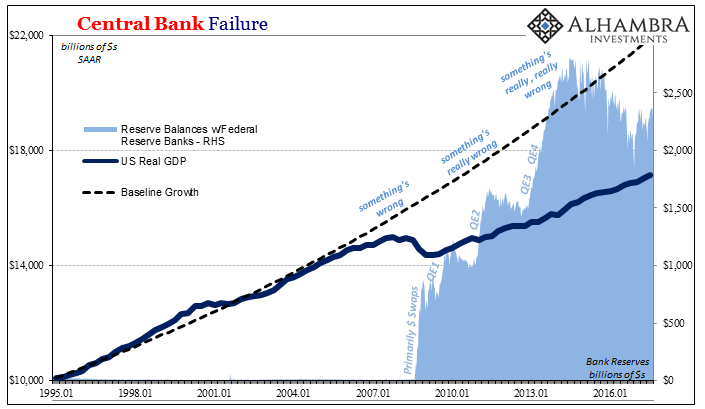

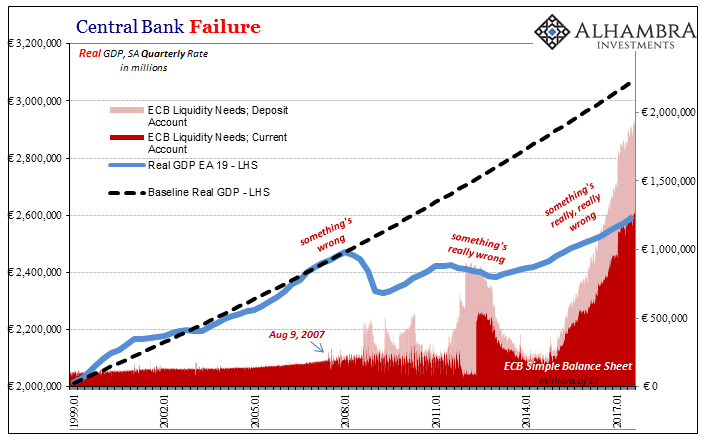

Because of this, “solutions” are everywhere presented only on that basis; meaning that China tries to fix China, the Fed tries to fix the US, the ECB only Europe, etc. Nobody bothers to fix the global issue with the eurodollar system. The result, unsurprisingly, is that nothing gets fixed anywhere.

Stay In Touch