Just before Christmas 2014, the Bureau of Economic Analysis upgraded Q3 2014 Real GDP to +5.0%. That represented a huge acceleration from earlier that year when during the depths of its Polar Vortex infused winter Q1 2014 GDP had contracted sharply (according to contemporary estimates). One need not be a betting man to hazard a correct guess as to which quarter gained all the attention and focus.

The statement from the White House three years ago was rather typical:

Today’s upward revision indicates that the economy grew in the third quarter at the fastest pace in over a decade. The strong GDP growth is consistent with a broad range of other indicators showing improvement in the labor market, increasing domestic energy security, and continued low health cost growth. The steps that we took early on to rescue our economy and rebuild it on a new foundation helped make 2014 already the strongest year for job growth since the 1990s.

This was a sentiment widely shared, an assurance, almost, that the worst was finally over and the recovery about to commence – if, indeed, it hadn’t already during that 5% whirlwind of activity.

Evidence is mounting that the U.S. economy is kicking into high gear.

Gross domestic product soared 5% on an annual basis in the third quarter, the government said on Tuesday.

To put that in perspective, it’s the strongest quarter of growth since 2003.

It simply never occurred to anyone that even two consecutive quarters of actually good growth would be anything other than what everyone was waiting for. Yet, all the warning signs were there, starting with that atrocious snow-driven first quarter. Everything is always extrapolated in a straight line, which for 2014 meant acceleration toward the stratosphere and never looking back.

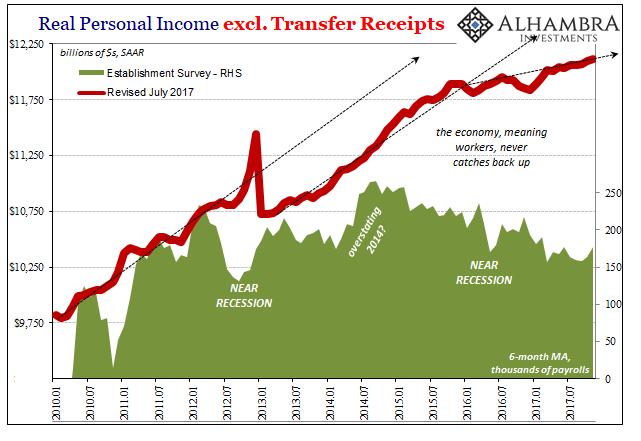

After having suffered through the abject disappointment of what did follow in 2015 and 2016, you would think there would have been deep and abiding interest in not making the same mistakes. Nope. Part of that stems from the fact that there isn’t now three years later an honest attempt to explain what happened. In the mainstream narrative, it’s as if the economy is still accelerating toward recovery, stalled out just temporarily.

There are, however, material differences between then and now – none of them favorable. By every serious metric, the economy on its upswing in 2017 is far less than it was in the same position in 2014. If that one ultimately failed, why should we expect things to be different this time after achieving an appreciably lower peak?

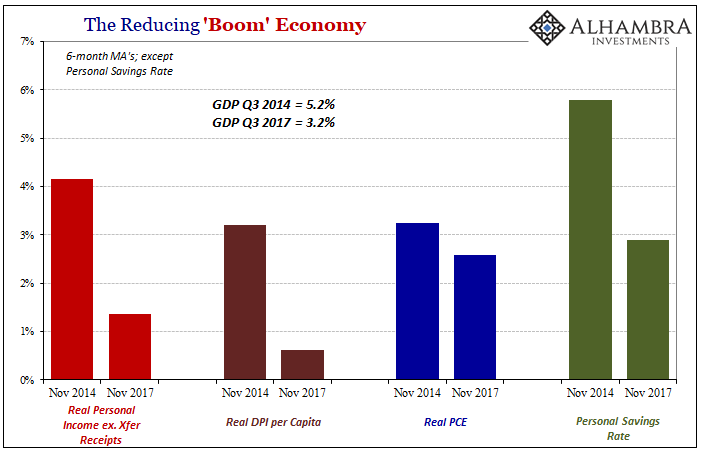

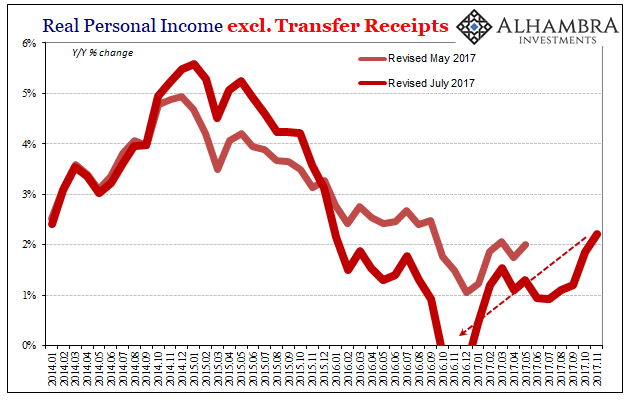

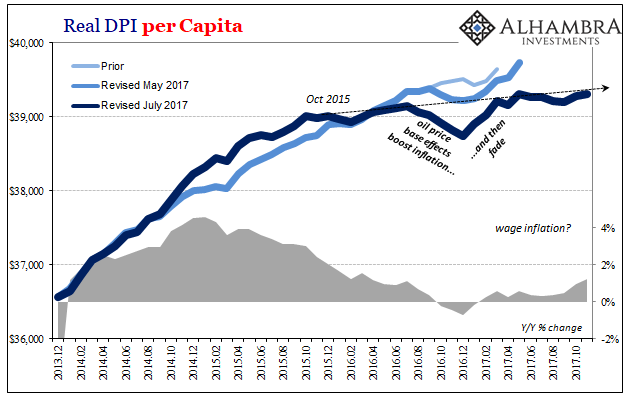

Ultimately, it comes down to income; always, always income. The BEA reported last week that Real Personal Income excluding Transfer Receipts was up 2.2% year-over-year in November 2017. That rate is actually on the high side for this year, driven upward by the base effects of being compared to worse conditions for real income last year (oil price effects).

In other words, it took a rather large and alarming (for the unbiased) drop in income in 2016 just to push the recent growth rate up to about half of what it was three years ago.

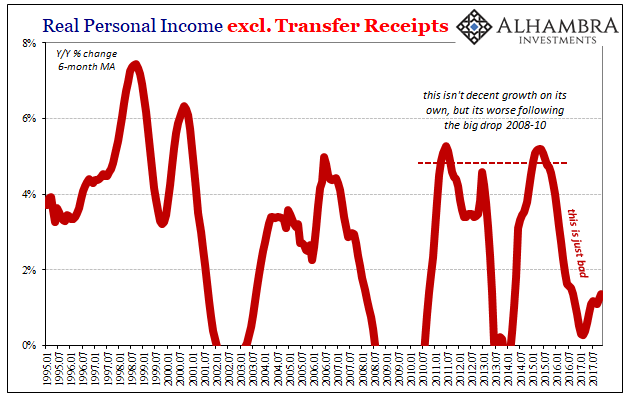

That level in 2014, a little over 4% growth on average, should have been enough to begin with for anyone seeing the economy still clearly constrained, therefore in no condition whatsoever to be set free for recovery. Four percent growth isn’t good, though it may seem that way now as far as income growth has fallen.

In November 1998, for example, Real Personal Income excluding Transfer Receipts was gaining on average 7.2%, a rate consistent with an actually robust labor market. Even in November 2000, just prior to the onset of the dot-com recession, the 6-month average was 6.1%.

Since income growth has so dramatically decelerated from that last upturn three years ago to this one now, you would expect that spending has, too. It has dropped back, but to a far smaller degree. Real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) were growing at an average 3.2% rate in November 2014, compared to just 2.6% as of the latest estimates for November 2017.

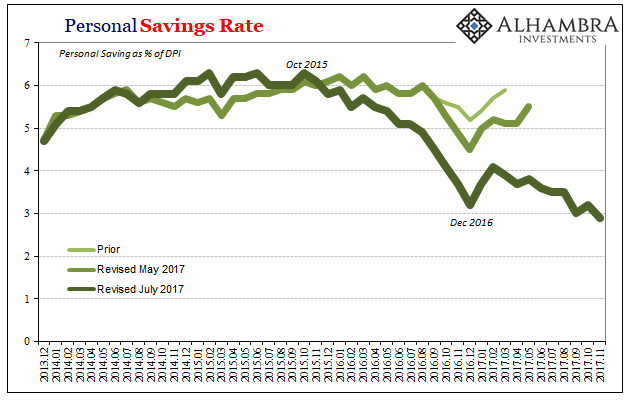

That’s rather remarkable given what has transpired in the slowing labor market. It can only mean that consumer savings, the difference between income and spending, has to have been the plugline variable. With such weak income growth since 2014, but with only a slightly slower spending preference (either real or nominal), that could only have meant a collapse in the savings rate.

The Personal Savings Rate fell below 3% in November 2017. At 2.9%, that’s the lowest since the summer of 2005.

This is the basis by which the current upswing, unlike that in 2014, is going to stick this time? No real recovery has ever been built on exceptionally weak income growth balanced by personal savings heading toward zero. This is the foundation instead for something worse than 2015-16, a lower high point from which to absorb the next, inevitable if “unexpected” set of “transitory” factors.

The economy is better than it was during the trough early in 2016, but that is no basis for comparison whatsoever. The only appropriate measure is peak to peak, the last one coming in late 2014. By that standard, there is a whole lot to be worried about, including that almost two years after that low point this appears to be as good as it might get (and “good” here is not good).

Many economists believe that the recent tax cuts and reform will be the key difference this time, boosting the current economy into something more like what the promise of 2014 was supposed to mean. Those are the same economists, though, who told us that there was nothing to worry about in 2014 (look at that exceptional 5% GDP!) if for no other reason than QE3.

If that episode proved anything, it was that economists don’t have much idea about the economy. Tax cuts can’t hurt (small change in the deficit doesn’t matter here, a drop in the bucket after the last ten years of them) but to believe that they are going to change the economic basis from what it is now to what it was supposed to be in 2015 is the same superficial nonsense as three years ago. The (global) economy is appreciably worse off today for all that did happen anyway despite starting from a much better position.

Stay In Touch