How much growth is enough? It’s a pretty simple question that upon close examination leaves no easy answers. This is a problem that has plagued economists since there were economists. Recognizing very real dangers on both sides, there is as much trouble about “too much” as “too little.”

The purpose of the modern central bank, then, is to moderate and chart a course between them. Whether it was ever wise to put that task upon them is another matter; this is where we are.

In 2018, most of them now believe for the first time in a decade they’ve achieved that balance (and they are the only ones allowed to make the determination). After spending all of that time closer to “too little”, mainstream commentary at the very least has been looking desperately toward “too much.” Not that we are there, but that the economic tumblers have finally all clicked together and a plausible path toward it might now be unlocked.

Even during the worst of economic depressions, the vast majority of people do just fine during it. What is at issue with regard to proper balance is the proportion of the population on the outside. During the thirties, at the worst of the Great Depression, three-quarters of the labor force was still employed – and that was catastrophic. Far worse was the fact that by the end of the decade, that proportion only improved to 83%.

The issue is always bifurcation, which is a more simplistic view of stratification. The flipside of the Great Depression is that even during the best of economic booms there are still those who don’t experience it. The real economic balance we all seek to achieve is to minimize this bifurcation as much as possible, for it can never be eliminated. To leave too many in it is to invite disaster no matter the recovery statistics (the real legacy of the Great Depression).

But it isn’t strictly a matter for employment, or where bifurcation becomes more stratification. By that I mean people who are employed may also be struggling; the unemployment rate is not comprehensive on the matter. They may be underemployed or may just perceive a general lack of opportunity that causes a very real change in expectations and therefore economic behavior. You may have a job that is minimal in nature but stay at it because you are more concerned about cutting loose to find a better proposition.

If there are too many facing such negative perceptions about opportunity, then the economy cannot be moving toward “too much.” It is instead well within the hard to define parameters of “too little.”

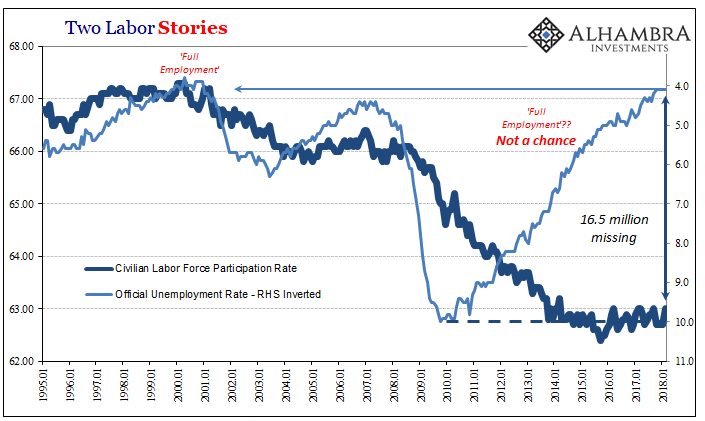

The main problem of the unemployment rate is that it remains uncorroborated. This is something new, certainly in our modern experience. Who would ever think the unemployment rate needs confirmation? It didn’t before simply because it easily fit with the circumstances. If it was low, that spoke about a more positive balance between “too little” and “too much.”

The current trend has suggested “too much” for several years now, but serious questions remain mostly in sustained favor toward “too little.”

Let’s be clear about housing and real estate. An economic advance is one defined by increasing home ownership, both as a matter of finance as well as economy. People want to own the place where they live. Before that, they want as adults to leave their parents’ domicile to live on their own. There is and has been a natural progression; dorm, apartment, starter home, and then on up to higher tiers. Some who skip college (and more should) go to the apartment as a first step.

A more balanced economy would find that process uninterrupted or reasonably balanced (never perfect).

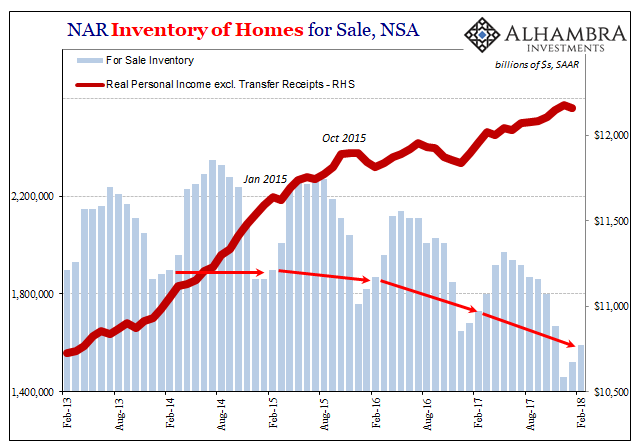

The housing statistics, however, are very clear here. “Something” is off. Further, the lower the unemployment rate has fallen over the past few years, the more imbalanced housing has become in contradiction to it.

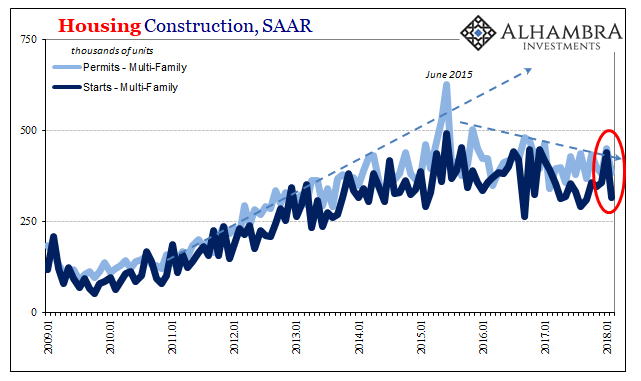

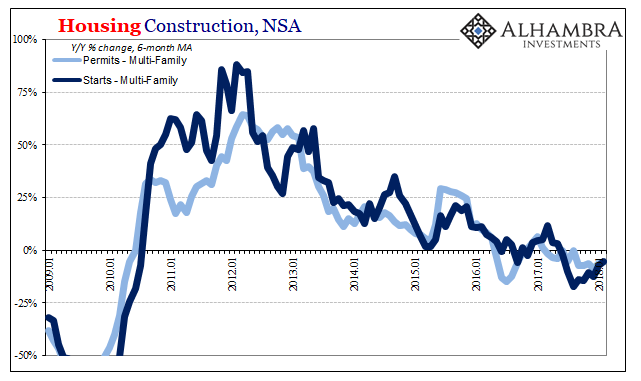

Start with apartment construction. Going back to the middle of 2015 (first clue), home builders have scaled back their construction projects in the multi-family segment. It’s not been a crash or loss-leading retreat, nor has it been a more reasonable reduction in construction activity following a period of over-active building.

The Census Bureau reported that for January 2018 multi-family starts jumped to the highest level in a year. Rather than indicating this part of the real estate market was finally about to express the same economic conditions as the unemployment rate, a sharp drop in the February 2018 estimates once more showed that these good months of data are just noise. Falling back to the same low level once again, the trend is lower even though more Americans are working, supposedly, and the economy is perceived at least in the mainstream as therefore booming.

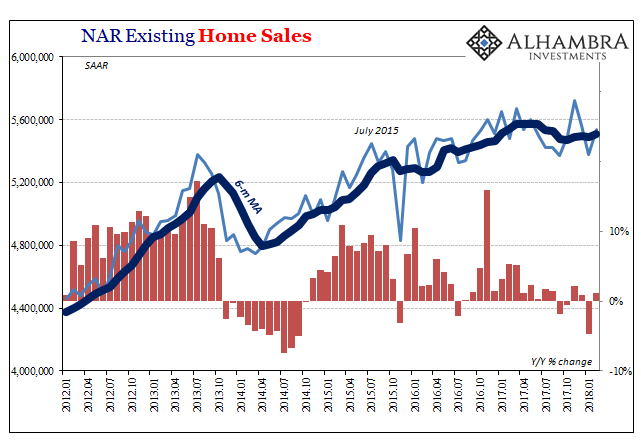

This deficiency spreads into the next tier in the home buying process, too. The National Association of Realtors (NAR) reports today that home resales remain lackluster. Rebounding from a pretty bad January, at 5.54 million (SAAR) that’s still consistent with the same low level of activity as the past few years (minus the clear hurricane interference).

There aren’t more homes being sold because there are fewer and fewer homes available to be sold. And a lot of those that should be on the market are what might be classified as starter homes. NAR President Elizabeth Mendenhall:

Realtors® in several markets note that entry-level homes for first-timers are hard to come by, which is contributing to their underperforming share of overall sales to start the year.

But if current owners of lower end structures aren’t willing to part with them, then builders should be actively supplementing the difference. This is as basic as basic economics gets.

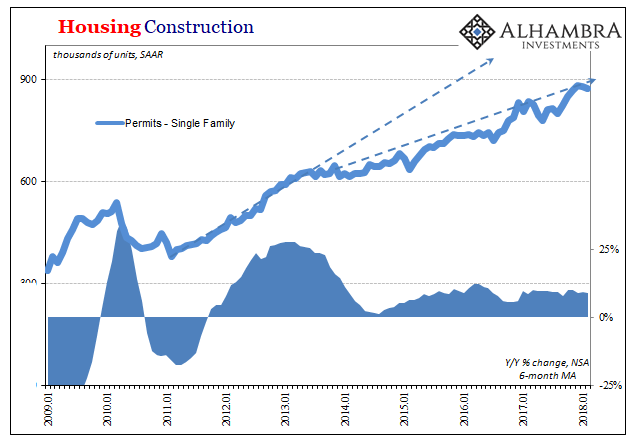

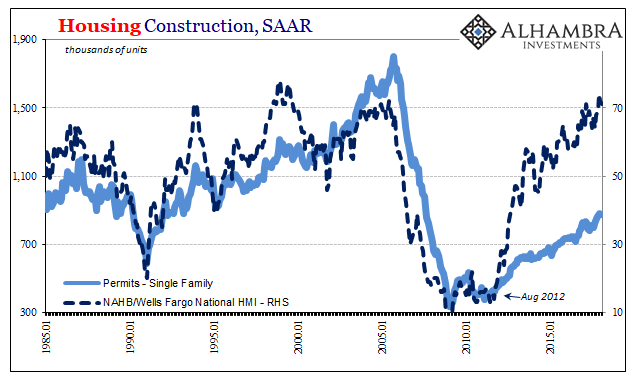

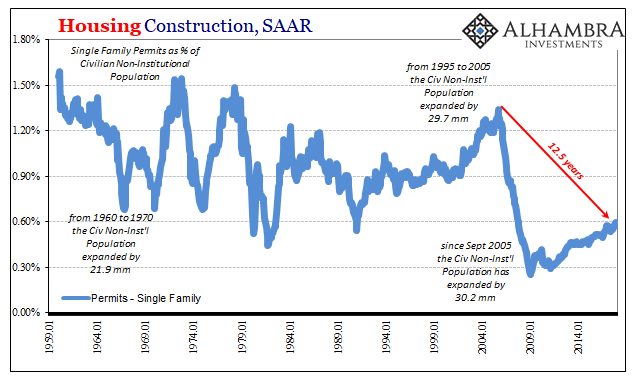

There is still solid growth in the single-family segment in contrast to multi-family. That, however, overstates the trend level to a considerable degree. Builders are constructing far fewer new units than they have at any point in post-war history. They are, at least, surprisingly happy about it.

That speaks to what seems to be the problem more generally. Homebuilder optimism is sky high even though activity is tremendously depressed – construction firms are, it appears, merely happy to have any little amount of activity they can get. They are satisfied with the minimum if only because perhaps fear worse (even though the bust is now almost ten years behind).

If that attitude is pervasive in construction, might it also not be so for workers, too? The unemployment rate is low, but it already excludes as many as 16 million Americans from its denominator who are in that “too little” category already. But of those who do have jobs and have managed to find work post-2008, might they perceive the economy in the same way as home builders?

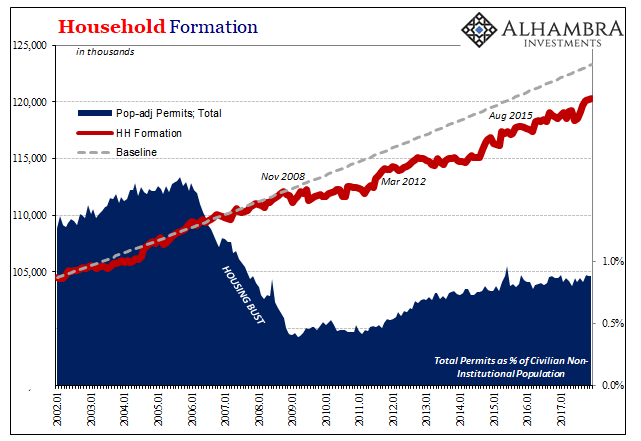

That would possibly account for the deficiencies all across the real estate market. Young adults may be working, but they aren’t confident enough about the economy to leave their parents and rent an apartment on their own. Young professionals who are also employed, may be similarly reluctant to sell what they have to trade up to a better home with a higher mortgage payment (as well as taxes, insurance, etc.).

They may even express positive sentiment about it, thinking more about the downside than an upside that for many appears quite limited. These are not the characteristics of a healthy economy facing “too much” growth.

This all would have gotten worse after 2015 once the labor market slowed as a consequence of the 2015-16 downturn neither the unemployment rate nor the mainstream media acknowledges; further driving a wedge between on-the-ground perceptions and conventional descriptions of the economy (which are always some version of “robust”, “strong”, and now “booming”).

What the real estate market is telling us is that the economy is not just stuck with “too little” growth, but that over the past few years despite GDP and the unemployment rate the proportion falling on the wrong side of bifurcation seems to have increased, not shrunk as would happen if things were moving toward better balance.

It may be exceedingly difficult to define the dividing line between “doing well” and “not doing well”, still in the current economy there are clearly too many questions about the latter for anything to be booming (or about to). The housing market is at least uniform in its indications, and it’s not what “rate hikes” are supposed to be about.

Stay In Touch