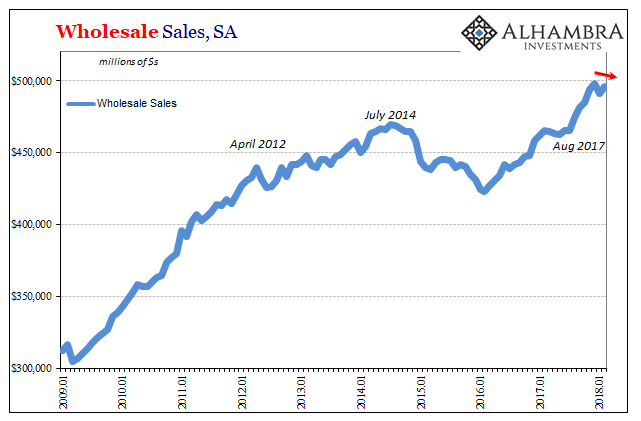

Wholesale sales, seasonally adjusted, bounced back moderately in February 2018 after a sharp decline (revised even lower) in January. Sales in the latest monthly figures are left still lower than in December and only slightly more than in November. This is the familiar aftermath of Harvey and Irma’s aftermath.

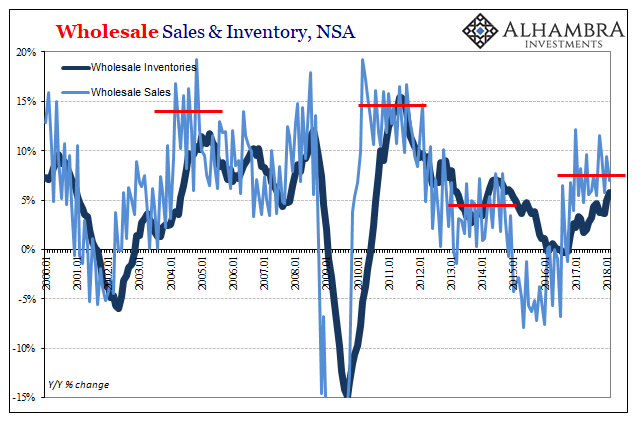

Unadjusted, year-over-year wholesale sales increased by just 6.9%. As the storm boost starts to fade, it appears that sales levels will start to quiet down again to be more in line with growth more clearly lackluster levels posted in the middle of last year. For the first time since September, the 6-month sales average declined.

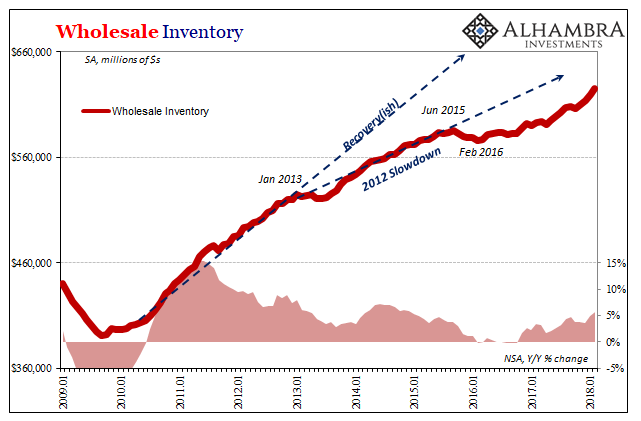

The more interesting part is inventory. Wholesale inventories are linked to US imports as the intermediate step between trade processing and retail handling before sale. The hurricanes produced a drawdown of inventory and then may have ignited some restocking on the wholesale level thereafter.

At some point over the past few months, that may have been augmented by additional foreign goods seeking entry before trade sanctions were put in place. How much before isn’t clear, nor is it for how much was sent inbound this way overall. There has been talk about trade wars for quite a long time since President Trump’s election, and we can reasonably assume that it was taken more serious toward the end of last year (and then even more so leading up to the actual proposals this year).

After declining a little in September and October in the months immediately following the hurricanes, wholesale inventories are up 3.2% over the four months since (including February 2018). That’s a substantial acceleration that has pushed the year-over-year (unadjusted) growth rate to almost 6% – the highest since December 2014.

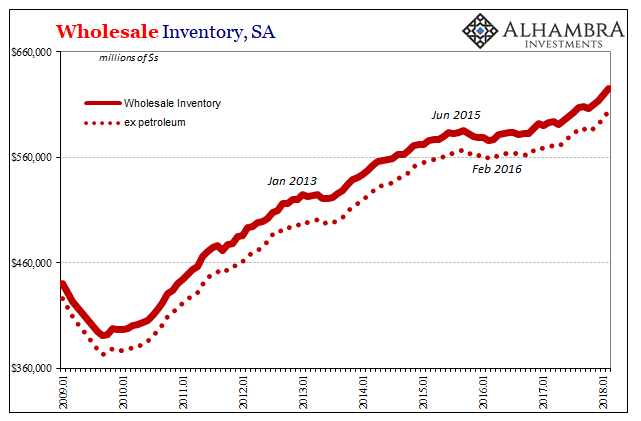

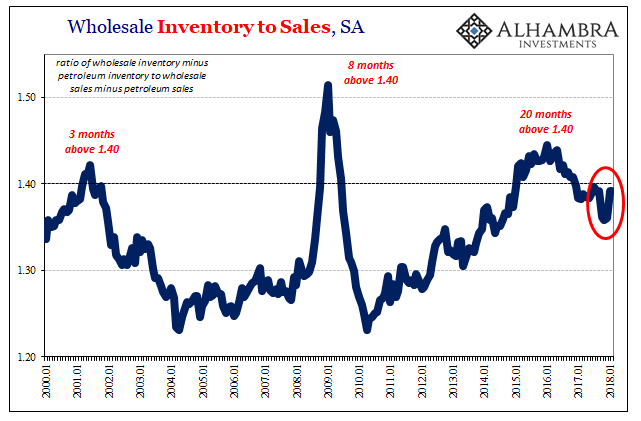

With sales lagging all over again, the inventory-to-sales ratio is right back near 1.40 (ex petroleum). Incredibly, that proportion has been stuck this high going all the way back to the start of 2015 – a run of now more than three years at levels more considerate of recession conditions than growth.

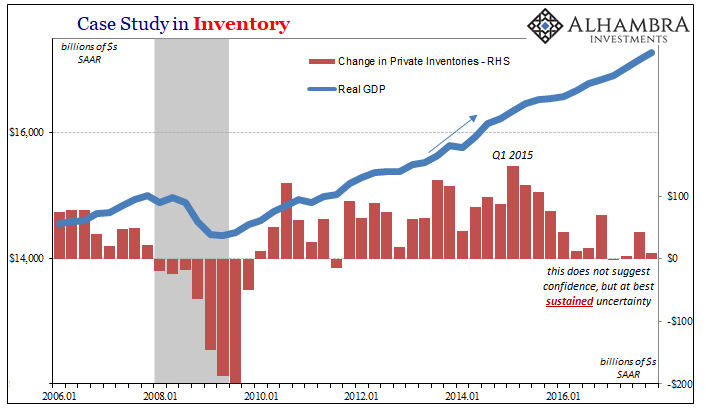

That’s because in a traditional business cycle firms all across the supply chain (outside as well as inside the US) are forced in recession to liquidate and drastically drawdown inventory. In recovery, producers work overtime to restock. Having been, by and large, operating outside that traditional framework for a decade, perhaps it’s not surprising that there hasn’t been any serious inventory focus in that way this whole time.

On the one side, Economists and policymakers (redundant) continue to claim that a pickup in economic growth is (always) around the corner. Outside of 2015-16 and what was a clear downturn, businesses not just on the wholesale level appeared to be willing (and able) to track inventory to those promises regardless of continued lower levels of sales.

Though inventory growth never achieved a healthy liquidation, it did economy-wide seem to reach something of a limit (around 1.40 ex petrol wholesale). For those nearly three years of a “manufacturing recession” during the “rising dollar” downturn the supply chain started to reject the growth premise.

In the two years since the trough of that near-recession, inventory levels have tread water – until recently. It suggests far more uncertainty over economic circumstances (and perceptions of the future) than during the 2013-14 upturn when higher inventory levels were firmly embraced. No liquidation, but not much restocking, either.

Thus, the trend over the past four or five months is perhaps a critical indication. The inflation hysteria scenario would have it that this uncertainty has ended, and the supply chain is already preparing for the acceleration that is sure to follow (inventory growth is exactly where inflationary behavior would propagate from; produce it now and put it in inventory before the costs of production, including labor costs, rise further).

Quite to the opposite, if it turns out nothing more than hurricanes and now the addition of China’s Trump-beating trade pulled forward, this inventory rather than contribute to acceleration would actually be depressive going forward (especially in China).

The bond market after having given the hysteria some brief thought has turned back toward the latter. Recurring “residual seasonality” in consumer spending won’t help, either.

Stay In Touch