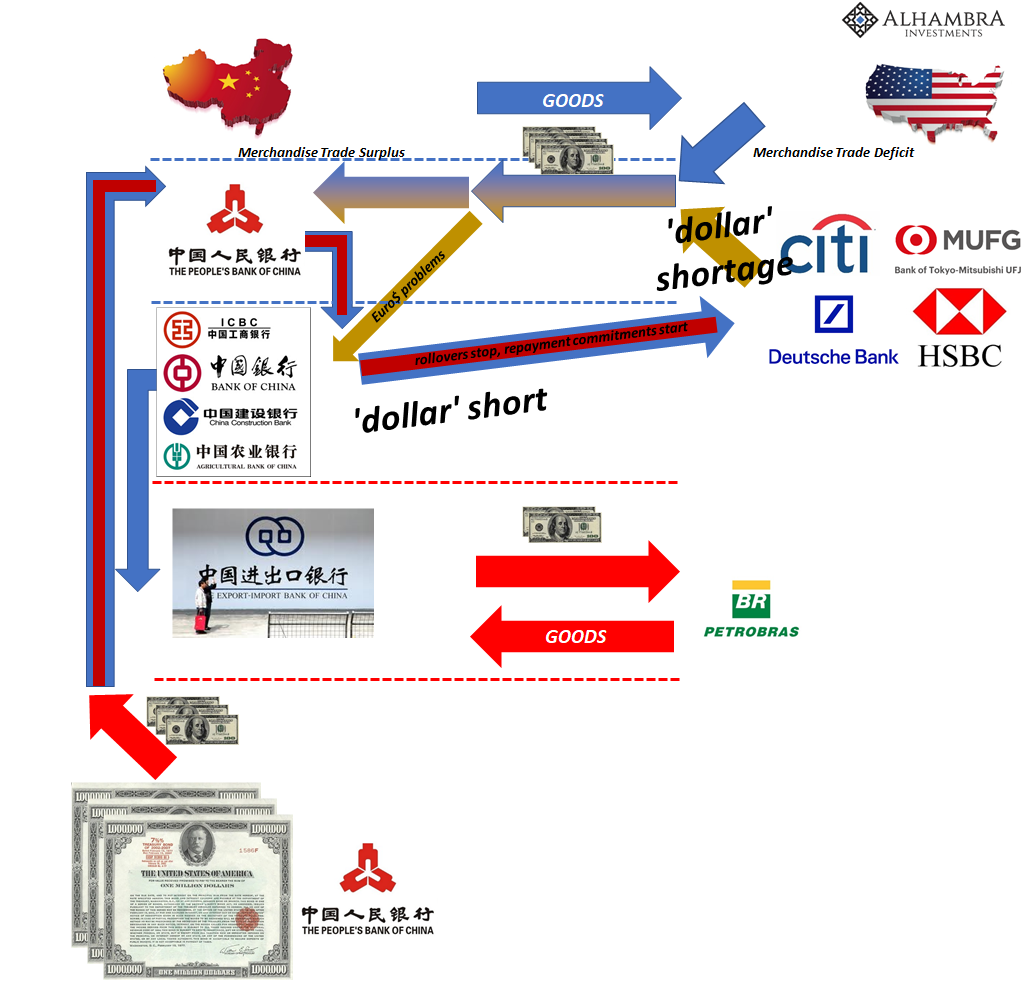

It’s worth revisiting the topic of the “rising dollar.” What determines its exchange value in the first place? Orthodox convention associates the general direction up or down with interest rate differentials, the infamous global carry trade. Not just any interest rate comps, either, but those of short-term money markets.

Thus, if the Federal Reserve is “raising rates” as it has been while other central banks hold their rates steady or increase them less robustly (as in, say, Hong Kong) the favorable spread in US$ rates should be dollar positive.

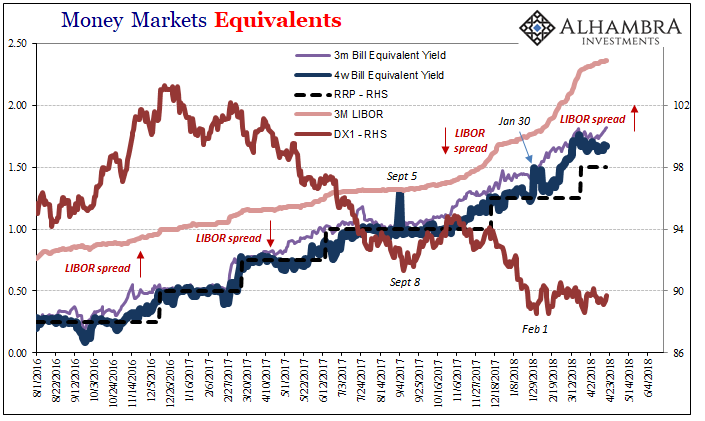

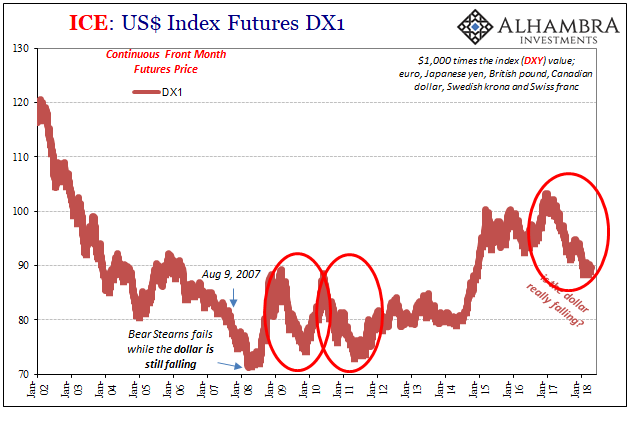

But that’s not what happened last year. As we well know, the “weak” or “falling” dollar took hold early on in 2017 just as US monetary policy became more assertive (relatively speaking). Since February 1, 2018, that has changed to where DXY has moved sideways even though “dollar” money rates have drawn higher with and without the Fed’s influence.

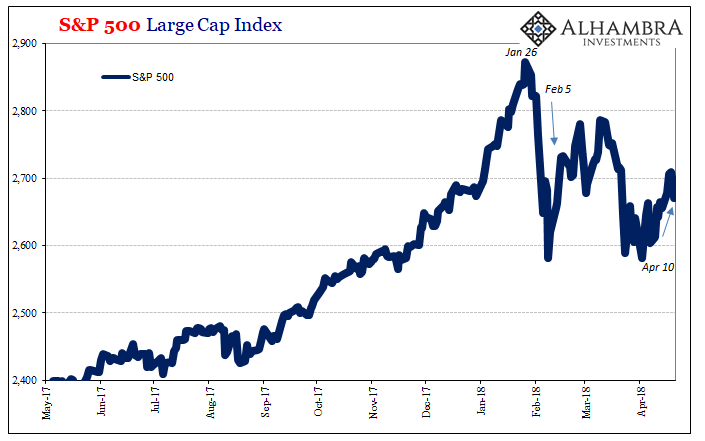

In retracing the liquidations of January/February, we can add one more piece to them. As noted before:

January 29 – stock liquidations start.

January 30 – 4-week bill yield shoots higher, from 128 bps near the RRP “floor” to 149 bps, a highly unusual single-day move.

To those we can put down one addition step, or change: DXY stops falling February 1.

It repeats the action from early September, too. Stocks weren’t liquidated then as they were starting in January, but the 4-week bill was on September 5. That same week repo fails spiked and DXY actually began a counter “rising” trend. It was also the same time that CNY reversed to mirror HKD’s sharp strengthening.

There may not be much actual volume in unsecured markets, but despite continuous demonization of LIBOR there obviously remains some information content in the fixings. A rising LIBOR spread, as in 2007-08, depicts rising liquidity risk perceived by banks operating across the whole global funding complex. Translating that into the dollar exchange, it’s an increase in pressures that indicates “dollar” funding is harder to come by globally. Increase demand or decrease supply, or both, should lead to the “dollar’s” rise as a matter of simple economics (small “e”).

That’s pretty much what we see above, or at least in the most recent turn the exchange value represented by DXY is no longer falling after the global liquidations registered in late January. This is the (almost regular) recurrence of the dollar shortage that has intermittently aggravated the separate and individual dollar shorts that exist throughout the worldwide eurodollar system.

Not only does this help in reconstructing the basis for any “rising dollar”, it also might temper the recent rebirth of “reflation” enthusiasm (which hasn’t yet resurrected the hysteria from before, but it certainly could). The dollar, or DXY, hasn’t really budged over the past week to ten days despite all that. Neither has LIBOR and its relevant spreads.

That might certainly change in the days ahead as sentiment perhaps shifts more broadly, but that it hasn’t casts some suspicions upon the latest BOND ROUT!!!! The last big one (relatively speaking) took place as the dollar was falling especially late December and much of January up until the liquidations set in. This time nominal yields are rising across the curve, but DXY shrugs.

What changed dating back to, say, April 10 or thereabouts?

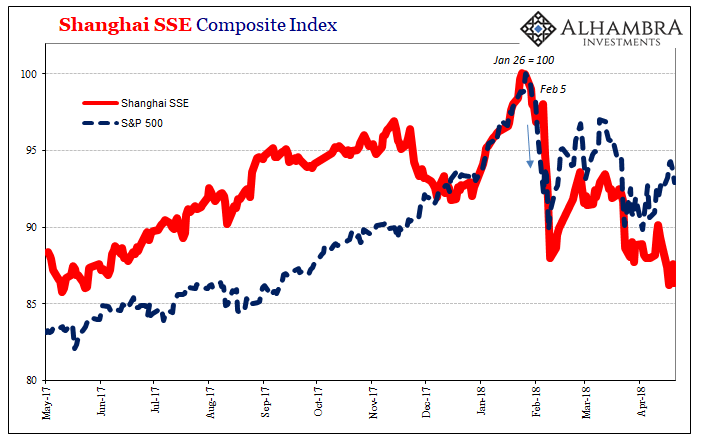

It’s also noticeable in the appearance of a slight divergence from what had been a pretty solid correlation through the liquidations and their aftermath. Chinese stocks sold off rather noticeably April 12 through April 17, while US stocks were contrarily bought. The 10-year UST yield that had been 2.79% on April 11 was 2.87% April 18 (and now just shy of 3.00%).

The American end seems to be relatively more inclined toward “reflation”; even if stocks were down the past two days. The overseas pieces importantly less so. Fragmentation being what it is, and has been ever since August 2007, this isn’t necessarily surprising. Possible relief over and of HKD would be less impacting in China and the Asian “dollar.” The question becomes one of potential convergence, and in which direction.

The dollar needn’t rise to be an issue, because it’s not the dollar’s movements that are the problem. That is but a symptom of the more hidden ends of the shadows. As has been the case throughout, the dollar’s exchange value has tended to be something of a lagging indication; it doesn’t change direction or move off its trend until things get more serious.

Stay In Touch