The year 2019 should be remembered as the year of repo. In finance, what happened in September was the most memorable occurrence of the last few years. Rate cuts were a strong contender, the first in over a decade, as was overseas turmoil. Both of those, however, stemmed from the same thing behind repo, a reminder that September’s repo rumble simply punctuated.

To be frank, every year should be the year of repo. But by and large nobody cares because no one can see it. They don’t have an immediate reason shoved in their faces for why that would be the case. For the first time since 2008, last year they were given that justification.

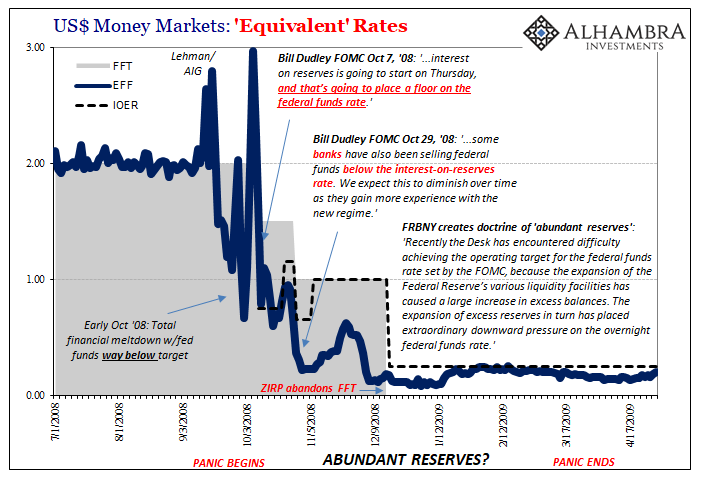

And all its attention was squandered – twice – on the wrong part of it. Milton Friedman was exactly right. Because central banks employ most of all the Economists in the world the story is told in the way they want to tell it. For repo, it is always from the perspective of bank reserves as the generalized stand-in for systemic “liquidity.”

That’s the exact wrong way to think about it. This is understandable from any policymaker’s point of view; the level of bank reserves is something they control. Therefore, if there is a problem with systemic liquidity the central banker who has the public thinking only about bank reserves he has at the ready his answer.

Just raise the level of bank reserves.

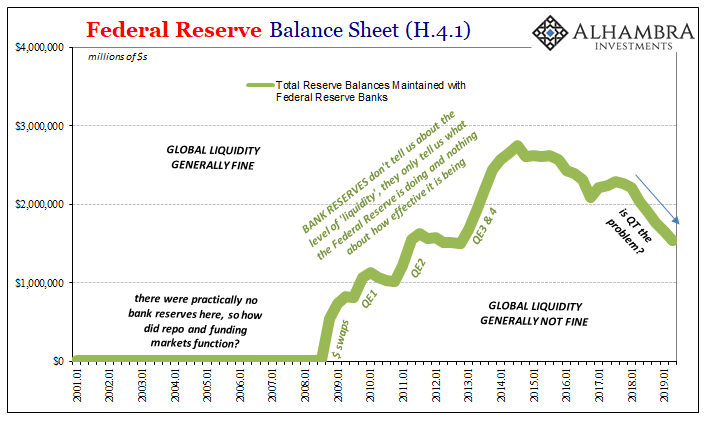

It was done four times in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis that was somehow global and somehow did its worst damage when those same reserves were called “abundant.” Nobody pays much attention to that paradox, either, for if they did they would easily figure out how it is no paradox at all.

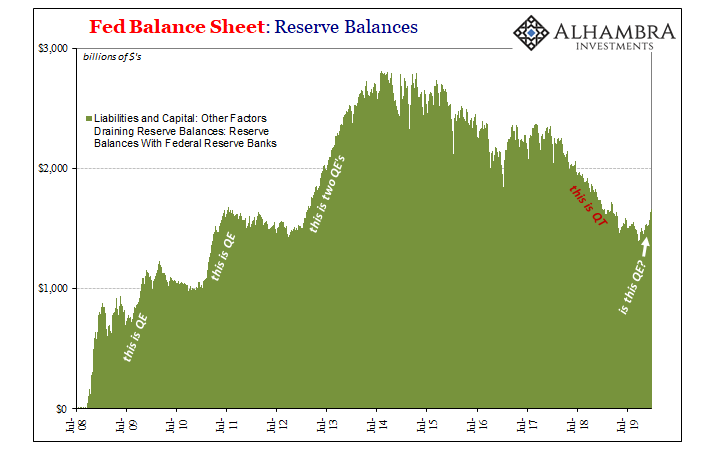

Expectations policy instead being what it is, Jay Powell’s Fed has performed marvelously. Not in terms of liquidity, but in terms of bank reserves. From a low of $1.394 trillion reached that week in September, the level has climbed to more than $1.651 trillion as of last week.

And now the debate rages: is this QE or, as authorities declare, not?

The real answer is: who cares!

The reason is very simple, but you have to come at it from the other way – the perspective that sees beyond bank reserves. Since I’ve written about this zoo before, I’ll just insert one of those times here:

The funding system used to be a real zoo, full of all sorts of exotic species of “liquidity” all provided by a private (and global) banking system which readily (and greedily) participated in it because it seemed to be one of only asymmetric positives – all return, no risk. Since Bear Stearns, it’s been all risk, no return. The animals in the zoo have more and more been left to die off over time.

There were all sorts of private forms of “reserves.” Very strange stuff that over time has gotten stranger still. But for our purposes here, I’ll keep this very simple.

Before October 2008, there was only private reserves and the world was filled to the brim with miracle economic growth and credit-driven asset bubbles. Not a hint of illiquidity or deflationary behavior anywhere. And at the same time, there were practically no public reserves, the bank reserves that the Federal Reserve conjures up with QE’s and the like (either large- or small-scale asset purchase programs).

Beginning August 2007, however, private reserves must’ve tailed off, a deficit which became so extreme no central bank action could counteract it. As a consequence, Ben Bernanke’s Fed responded with “abundant” reserves – but these were public reserves, not those private forms which had exclusively predominated.

Private reserves good = global growth, bubbly credit markets, and no need for public reserves. Private reserves bad = lack of global growth, unstable to deflationary credit markets, and a surplus, reportedly, of public reserves. The one goes up, the other isn’t needed. The former goes down, suddenly there ends up being a lot of the latter.

That’s the only relationship you should be concerned about. When the Fed is increasing the level of public reserves, it isn’t doing so in a vacuum – yet, that is exactly how it is characterized. As additive money printing, as powerful stimulus being piled on top of ceteris paribus.

We know, however, that’s just not the case – or, more specifically, that there is far more to the story way behind the scenes. The Fed instead is reacting to insufficient levels of private reserves, or, more accurately, the negative effects we see when that happens, and that is what leads authorities to increase the aggregate balance of public reserves.

But which one is more important?

Obviously, history shows conclusively it is what is taking place on the private side that ultimately matters. The level of public reserves can be and remain “abundant”, as has been the case through each of these Euro$ episodes to date, to no real effect. But they make everyone talk about stimulus and money printing.

The Federal Reserve is raising the level of public reserves which everyone can see (rather the whole point) without any mention of what must be going on with private reserves most people cannot because they don’t know a single thing about them. Or that there are and must be them.

And that’s the final shame for last year’s year of repo. Because if you think about QT for any small length of time, you absolutely have to factor private reserves into the situation.

After all, the Fed was actually counting on them.

Private reserves had been the whole point behind QT in the first place. As I attempted to describe back on the first day of September’s repo rumble:

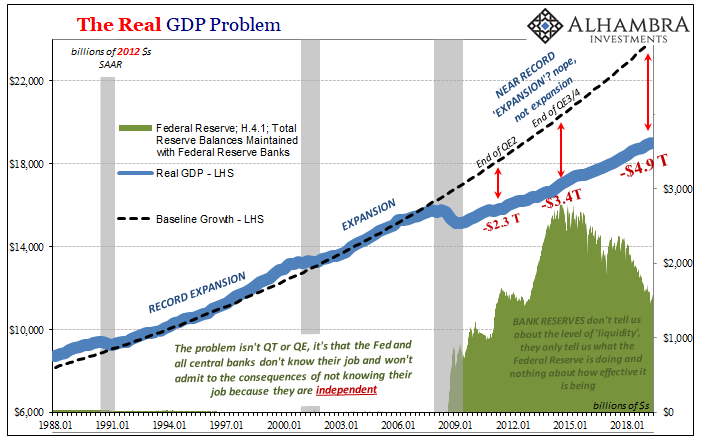

The whole point of QT was to move from B to C; to wean the global liquidity environment off of the Fed’s presumed liquidity capacities and to hand it back to…someone. The FOMC began to reduce its balance sheet again, the level of bank reserves dropped and what was supposed to follow was no one noticing either of those things.

Point A was exclusively private reserves giving way to the post-crisis period of Point B populated by these trillions of public reserves. QT was the waypoint between Point B and Point C, the latter being re-established normalcy.

In other words, the whole point of QT was the Fed anticipating how private reserves were going to once more dominate US$ liquidity. As the level of public reserves was quite purposefully drained, our central bankers had been anticipating that private reserves would more than make up for that; how they already must have. So much so, no one would ever really have noticed QT. Thus, QT could theoretically take public reserves down almost (accounting for several autonomous factors, including, interestingly, the foreign repo pool) back to zero.

As I wrote back in September, “C wasn’t just going to be good it was going to be fun again.”

The abrupt end of QT, before the repo rumble, all the way back on the first day of August 2019, shattered the fantasy. The visible level of public reserves had been falling but throughout the prior year and a half there were any number of warning signs that the hidden level of private reserves wasn’t picking up the slack as had been expected.

For that reason, as well the more complicated picture, the plan failed. And now the Fed is back to QE, not-QE, who cares. The level of bank reserves, public reserves, is rising once more because…what must be happening in private reserves was never sufficient. That’s why QT seemed problematic from the very start, and why ultimately it was shut down prematurely.

QT was the byword for monetary normalcy. For it to have succeeded, it required the private liquidity system to already have achieved that very thing – a positive condition that every central banker had assured us had been unquestionably reached years ago (Yellen talked about it during her entire tenure).

Therefore, if QT was unsuccessful, and it clearly was, what must we conclude about the private liquidity system?

Not normal. Still.

Jay Powell is actually doing us a favor by pointing that out with the Fed’s latest actions.

So, despite 2019 being the year of repo we begin 2020 under the debate of whether the Fed is engaging in QE or not rather than having a public awakening about what that actually means for anything that matters. What’s hidden remains hidden, even though it is somewhat illuminated by what is visible. The lack of appreciation, the lacking frame of reference for understanding all this, it is a testament to the power of central bankers to control only the narrative for they have no control over the money.

Public reserves are inversely, and indirectly, related to the vastly more important (and complex) level of private reserves.

That was all QT ever was; central bankers being wrong…again. They said raising the level of public reserves from zero would solve the crisis; it didn’t. They then said an even higher balance of public reserves would repair the damage and create a recovery; it didn’t. Finally, they said those things had been accomplished anyway, a fact which would be made known by the anticipated trouble-free hand-off from B to C, paving the way for the world to be able to go back to normal; didn’t happen, either.

For a whole decade, all anyone has talked about was public reserves. In light of yet another false dawn, taking a step back, you might instead get a sense that they just don’t matter all that much. But even now, they continue to be the only thing on anyone’s mind.

QE or not QE. WHO CARES!!!!!

And that explains the last decade, as well as how the next one will begin.

Stay In Touch