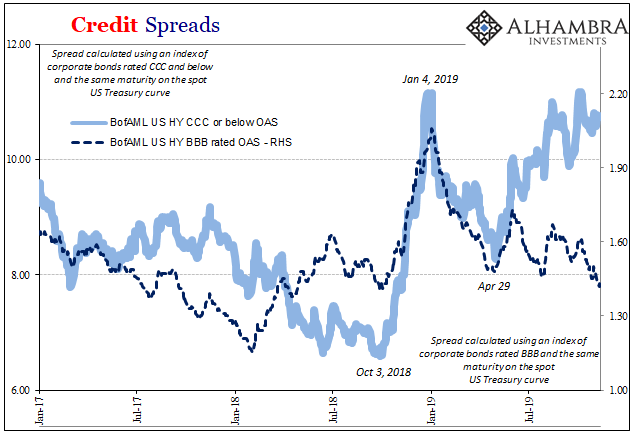

There’s trouble brewing in a particular sector of the corporate bond market. It’s not really new trouble, merely the continuation of doubts and angst that have existed for more than a year already. What’s different now is that it is finally causing more open disruptions, and thus sparking our interest as to what it might mean well beyond this specific market or corporate finance.

Including and especially what it could do to repo.

What I’m writing about is CLO’s, or collateralized loan obligations. It’s a fancy term for securitized corporate loans. A bunch of these are pooled together in the same way mortgage loans used to be more than a decade ago. Particular tranches are assigned cash flow and loss priorities, rendering the lower parts of the structure as solid near risk-free securities.

And, in fact, they are. Even among the worst junk of the housing bubble era, the senior and super senior tranches performed admirably – just as they were designed. I’m still not aware of any that caused actual cash losses, meaning credit. “Thickness”, or the amount of loss protection provided by the tranches above them, was never the issue.

The whole point of securitization was and remains one goal. As I wrote a few months ago on the topic of repo:

We can spend an awful lot of time diagramming and detailing these instruments [ABS CDO’s; another form of securitized financial structures] and those like them, what they were used for and why banks seemed so enamored with the type. In fact, I’ve already done so elsewhere (Eurodollar University). ABS CDO’s can be of a couple different kinds but what they all have in common is that they make what is erstwhile illiquid assets into a liquid security.

What’s so important about that? In a word: repo.

You can’t show up at JP Morgan’s repo desk with a lot of papers holding title to thousands of mortgages and expect to fund them on the basis of those individual loans. That doesn’t work. For one, the cash owner, the interbank repo lender, wants collateral that is highly liquid because that way the cash owner knows the collateral being received isn’t going to move much while in his possession.

Though the senior and super senior mortgage bond tranches weren’t realistically exposed to credit losses, they were exposed to illiquid markets and pricing schemes that were unrealistic. The repo market doesn’t care, however, an unforgiving and brutal place where all that matters to the counterparty on the other side is that pricing scheme.

If an asset’s price can move quite a lot in a very little amount of time, then the repo market won’t like that asset regardless of any other characteristic; credit and otherwise.

And the reason you pool together corporate loans, like mortgage bonds, is because you want a securitized package tailormade for repo funding.

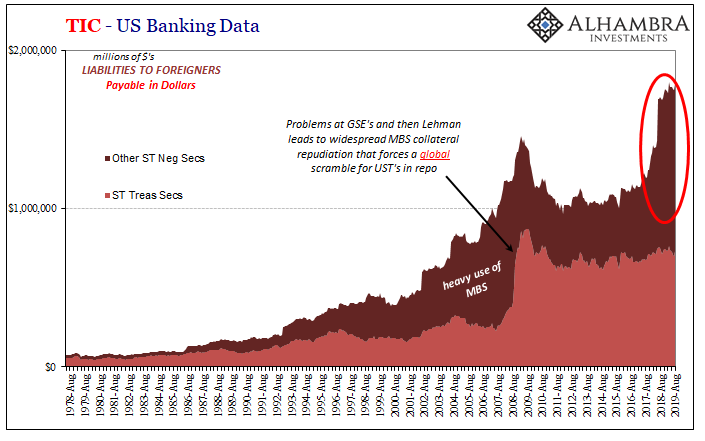

Whereas MBS and the like found their way into the repo collateral chains before 2007, CLO’s (and Eurobonds, and Eurobond CLO’s) have done something similar particularly since 2012 and 2013 (like stocks, the CLO market was really enthusiastic about the prospects for QE3). But not in a straightforward way, more likely as the initiating link in a collateral transformation chain that in its most vanilla form gives a simple repo transaction a couple of additional (and concealed) legs.

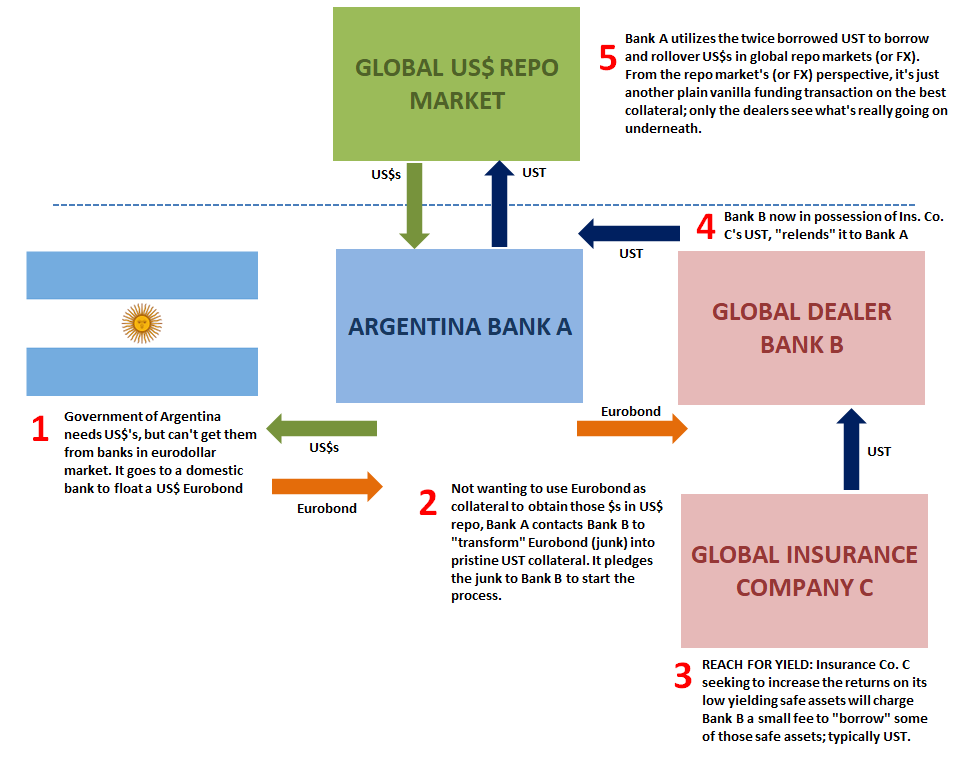

I gave an example of this in the most recent edition of my new Follow The Money series (registration required) which dealt specifically with CLOs’ offshore cousin, the Eurobond binge. The diagram below is taken from that other work but applies all the same – just swap the Argentine government for a risky corporate lender, Bank A for some domestic non-bank, and the orange arrow Eurobond for most varieties of CLO’s.

The problem, again, with how MBS was used in the same way a decade ago was uncertainty about pricing – the thing that kills collateral potential in repo and repo transformation. In our example above, neither the repo market nor Bank B has any interest in being a part of using an increasingly risky and therefore potentially illiquid asset in the chain.

And what we are seeing recently are more and more indications of risky and irregularly priced CLO’s and corporate junk more generally. From the WSJ a few days ago:

Some securities in the $680 billion market for collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, lost about 5% in October, reflecting worries about rising risk in the complex investment vehicles. The declines were a rare stumble for the CLO market, which has grown by about $350 billion in the past three years, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence, fueled by demand from government pensions, hedge funds and other yield-hungry investors.

I think that estimate of $350 billion understates the level by quite a bit; likely just a domestic snapshot of the more visible parts. How many more CLO’s are out there offshore in Eurobond-land? If you ask the Treasury Department, it “found” about $280 billion more in June 2018 alone.

In other words, there are tons and tons of these things floating around the offshore financial world. And a lot of those that are out there have wound up one way or another as the originating entry into a collateral chain; there is likely to be widespread repo market, collateral exposure.

If concerns about this persist and even grow no matter what the Fed or any other central bank does, no matter how many times Jay Powell says the words “repo” and “operation” (which aren’t actually repo operations in the respect they have nothing directly to do with the repo market itself), there’s going to be doubts about provenance across the collateral landscape.

Global collateral landscape.

What we’ve seen in 2019 is just that. After 2018’s broader landmine, it seems to have initiated a different look at especially the high yield corporate market. A more durable re-thinking from the bottom ends. The higher rated stuff has been bid back to lower spreads. The lower rated potentially more illiquid tiers, have not.

If it seems like the bond market is just waiting for the other shoe to drop, it’s likely to be CLO’s that everyone is waiting on; especially those that have made such a huge if obscured splash outside the United States. And the more doubts about the viability of the global economy continue to seep into the mix, the more those on the inside can see how potentially explosive the possible repo unwind could become.

Liquidity risks.

Risky corporate bond products, suspect repo collateral chains, global downturn, and the growing prospects for illiquid pricing. A bad combination. Even if an especially vigilant forest ranger can’t predict exactly when or where a wildfire might start, they can recognize the right mix of of ingredients which make one more likely. In global repo, money dealers are the forest rangers.

Stay In Touch