Can a PMI actually hit zero? We may be about to find out. According to IHS Markit, the Eurozone’s economy is already flirting with that boundary this month. The services index plummeted way beyond March’s revised estimate of 26.4, an astoundingly alarming number in its own way. For April, though, down even more all the way to 11.7.

That meant the composite was dragged down to 13.5, obviously a record low (dating back to 1998). And it only manages to come in that high because the manufacturing PMI is being artificially boosted in several subcomponents. While the output index in this other segment dropped to 18.4 in April, the overall manufacturing number stuck around at 33.6 (down from 44.5 in March).

But we knew it would be bad. That’s not the major bet; whatever the nastiness in the short run there are apparently a huge number across the world still thinking that when the shutdowns are lifted everything goes back to normal. Right back to normal, almost instantaneously. The “V” case.

That was going to be a difficult feat to begin with, complicated all the more by the absolutely terrifying depths the initial contraction is pulling. The larger the hole, the harder it is going to be to climb back out.

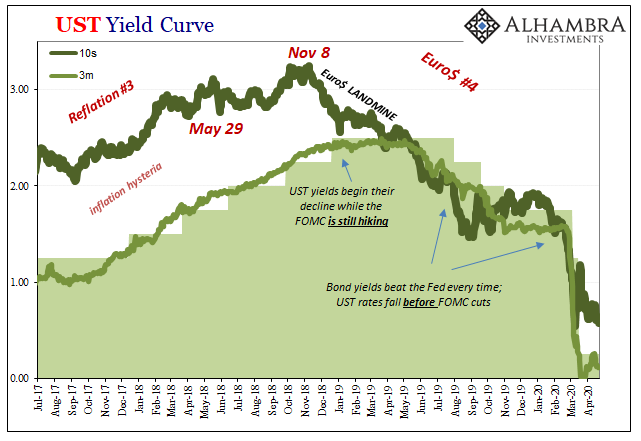

And it’s complicated by a real world that is messy in the best of situations. Throw on top another GFC roiling markets, still, and the “V” case shrinks to a distant outlier hope shorn of any reasonable basis.

Thus, Markit notes of its expectations components starting in Europe, especially manufacturing, that the degree of pessimism looking out over the next year has never been greater. The only thing even potentially robust right now is serious longer run doubt.

The reason is fragility; as in, the European economy in particular but the whole global economy, too, had been sliding toward recession before COVID-19 was ever identified. That does matter.

Why?

If businesses were already pushed toward the brink, they aren’t going to be able to withstand these further massive pressures. They had no room for error, no cash or not enough of a profit cushion from what many had merely presumed had been an economic boom to leave them with a few months of spare capacity.

You can’t absorb even a couple of months of huge cash losses, paying all or most of your workers, if you’re already in the hole.

Instead, without any space on either their top or bottom lines, it’s right to the unemployment line for far more employees than might’ve been the softer case had the economy actually been in good shape heading into the shutdown.

And that’s exactly what politicians and officials had been thinking here in the United States. They may not have been so self-deluded in Europe, knowing full well the trouble that pre-existed the outbreak of the disease, here in America it was a completely different story from Trump on down.

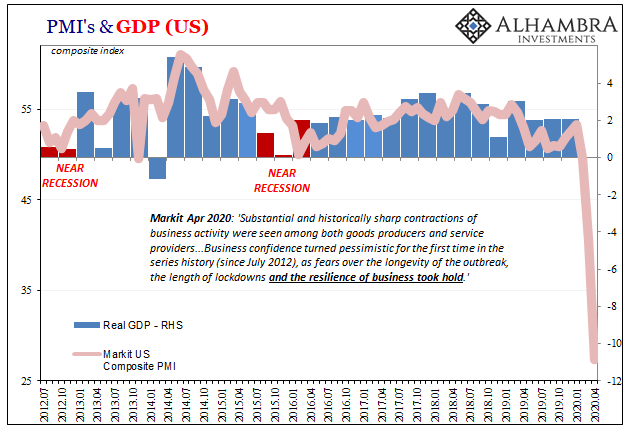

It’s proving to be a disaster. The numbers continue to confirm that, like Europe, the US economic situation was indeed fragile, too. Businesses here had already suffered the downturn in 2019, no mere recession “scare”, and they were left with little to no room to endure more strain let alone pressure this absolute (meaning both shutdown and GFC2).

That’s why now 26 million Americans have filed for unemployment in just five weeks; businesses which were already weak, not fattened, couldn’t stand it from the very start, being broken completely down with breathtaking speed.

In IHS Markit’s terms, that meant for April’s PMI numbers another unprecedented collapse. The manufacturing index “held up” at 36.9, artificially and yet a 133-month low, while services plummeted to 27.0 from a revised 39.8 in March.

Combined, the composite PMI registered 27.4 (on consensus expectations of 34.2 to 38.7), substantially less than every one of the worst months in 2009.

Also like Europe, it was more expectations about the future captured by these somewhat crude sentiment surveys which should concern everyone. According to Markit, US business confidence is the lowest ever, as firms are desperately uncertain about the shutdown as well as their ability, and consumers’ ability, to withstand the whole thing (“fears” over “the resilience of business” highlighted on the chart above).

The expectation at least as set by Jay Powell and his parrots in the financial media is that though it will be a historic dislocation in the short run, moving past the unpleasantness will be a satisfying, healing return to normal in very short order. Floods of global “stimulus” will make sure of that.

Yet, like many markets, it doesn’t seem as if local businesses (or consumers, as workers) anywhere in the world (Japan’s Jinbun composite PMI all of 27.8, too, in April) are actually picking up that message. The entire global situation was already fragile to begin with, and these morons went at it with a sledge hammer thinking that there was strength at the start to rely on, and power in “stimulus” to alleviate any ill developments.

That’s what all the models told them, the same models that haven’t been right about anything, especially 2019, in decades.

Forget the “V.” The task before us now is to figure out how deep the “L” goes and if there might be any substantially positive slope to its lower reaches on the way out.

PMI’s are reaching record lows, and we haven’t even begun second and third order effects. Factors like credit card companies cutting personal limits and mortgage lenders refusing even the most qualified applicants, to name a few examples. And those before considering what another wave of GFC2 might do with Jay Powell, and the IMF, already in full-on mode.

Stay In Touch