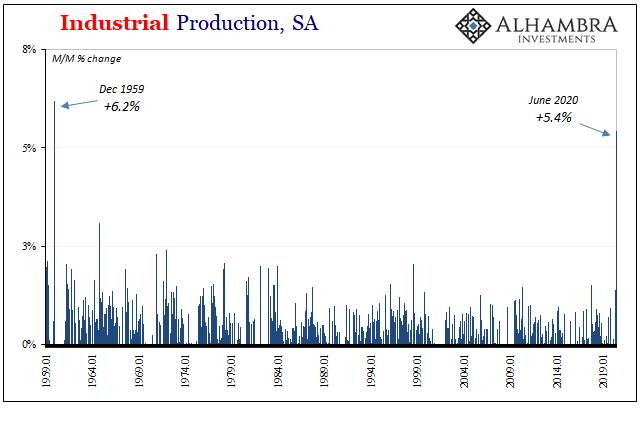

It does sound impressive, maybe even encouraging. After two months of being shut down, industry in the US rebounded in June 2020 by the most in 60 years, and not one month during those intervening six decades was ever close. You have to go all the way back to December 1959 not just to find a larger monthly increase but any gain even in the same ballpark. This is yet another gigantic positive and a key one at that.

But, as usual, that’s where the good news ends. If your sense of the economy is taken only from this side then it might seem sort of “V”-ish. The only reason for such huge plus side numbers was the unthinkable scale of the crash which preceded it.

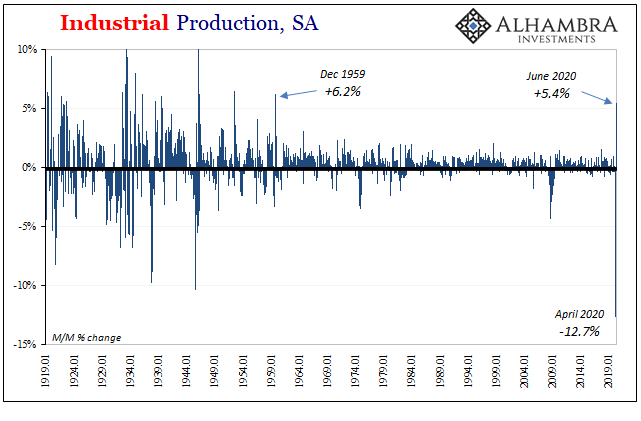

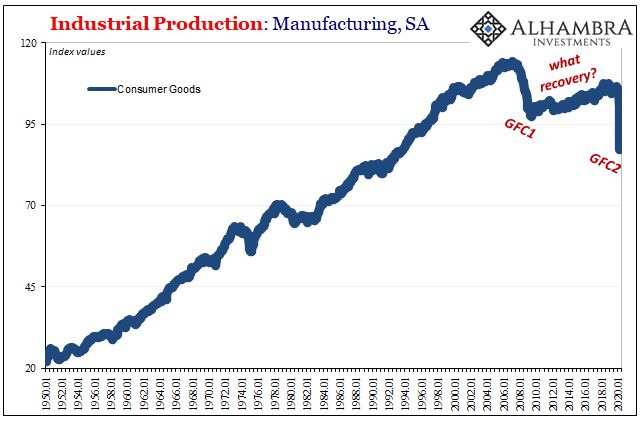

Industrial Production is the oldest continuous economic data available, consistent numbers dating back to January 1919. The data nearly touches World War I and begins with the globe tackling the Spanish flu. And yet, what happened back in April was unprecedented for American industry; the worst on record for figures spanning more than a century.

The last time there had been a double-digit decline, the previous record, it was August 1945 when massive American demobilization began after Japan surrendered to end World War II. The only other months in close comparison were two late in 1937, the deep wave of depression-within-a-depression.

Combined with a 4% contraction in March 2020, Industrial Production collapsed by nearly 17% together in those two recent months; or, about the same amount as during November and December 1937 collectively.

While unquestionably awful, those arguing for the “V” case counter that, thank god, it was only those two months. That’s what’s good about June’s rise and even May’s much smaller gain, for that matter. We all knew it would be a disaster, but it’s over now. After all, the contraction in ’37 lasted a full year.

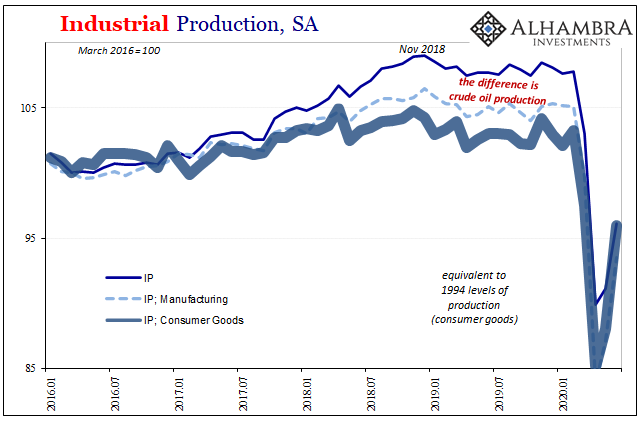

In the one sense, that’s true. The COVID-19 mess has been, so far, limited to just the two months. However, the downturn which had preceded them, while not nearly so severe as the Great Depression it had already sapped a great deal of marginal strength. US industry, like the rest of the global economy, had been experiencing a prolonged globally synchronized downturn lingering for a year and a quarter before ever getting to the coronavirus.

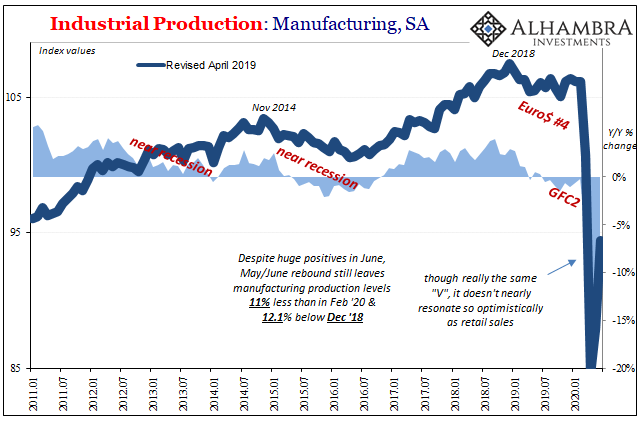

Even though June was up more than 5% from May, and 6.8% from April’s bottom, production levels in all industries remain nearly 11% less than February and just about 12% below the peak set all way back in December 2018. It’s not just the level of decline, the amount of time matters, too.

Together, these are what make this rebound seem so small – because it is. Gigantic positives aside, even this massive momentum generated by what had been a reopening frenzy hasn’t convinced the production side of the economy to match it. Why not?

Because as much as sales may have recovered from the bottom, they remain severely depressed, too. And what makes the worst contractions the worst contractions is the level of lost opportunity and business caught up in those massive downsides. If there were only non-economic factors at work here, then June, at the very least, would have shown up that way.

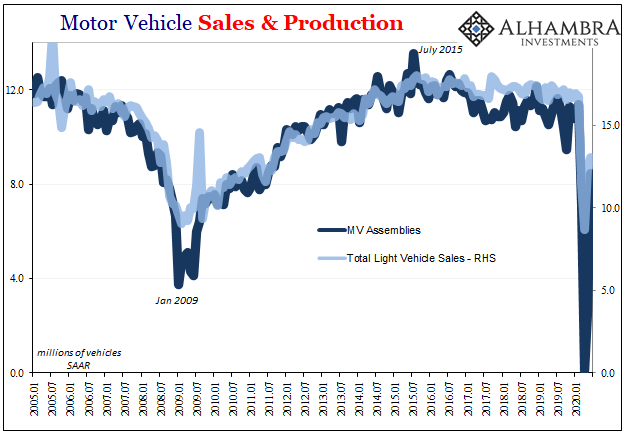

Consider auto sales and production, for example. Total US sales had been in a mild downturn consistent with the globally synchronized direction. According to the BEA, in February 2020 sales hit a relatively modest 16.75 million (SAAR). The following month, March, sales came in under 11.4 million; April just 8.7 million.

In April alone, that was about 8 million (annual rate) auto sales that never happened which would have if not for the interruption (assuming Euro$ #4 didn’t tilt sales even further downward than the trajectory they had already traversed to that point). If COVID-19 is all there was to it, then a good portion of that 8 million should have shown up in one of the months closely following – on top of moving briskly back closer to a regular month of near 17 million.

In other words, why weren’t June sales so much closer to a regular month if not even better (instead of still just 13 million)? If the non-economic factor is all there is to consider, then sales were only postponed (production, too) during March and April not lost forever. We should be seeing not just gigantic positives when compared to the trough as the shutdown eases, but, even better, ginormous numbers on top of “regular” monthly paces being restored by reopening.

More like normal months plus two months to make up for.

Like 1937, because of this destruction every part of the economy must adjust to a lower level baseline – by making further (negative economic) adjustments. Over time, given enough time, maybe that amounts to some distant recovery way off into the future (as we know from mainstream models, not even the optimists are thinking about getting back to 2019 levels before 2022 at the earliest). Until that time, economic potential, for lack of a better term, is reduced the longer it takes (and, again, it’s already been a year and a half).

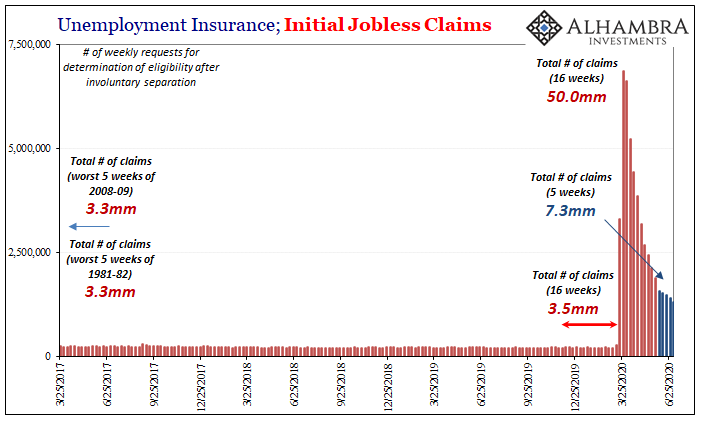

To put it very simply, gigantic positives notwithstanding, these IP numbers are actually and chillingly consistent with jobless claims. We know that adjustments are being made right now because the rebound just isn’t much of one; a massive amount of demand and business has been destroyed, not merely postponed.

The full weight of the consequences isn’t something we’ll see right away, either. The second and third order effects (look at bank loan losses, for one thing) will hit with a thud after a lag. Despite moving back higher again, what looked like a “V” for a few tantalizing months ends up getting walloped by a very different sort of reality, leaving us with yet another “L” to try and deal with.

Stay In Touch